A Thematic Unmasking of Majora's Mask

Written with advice and editing from Hunter McGee and Matt Louscher

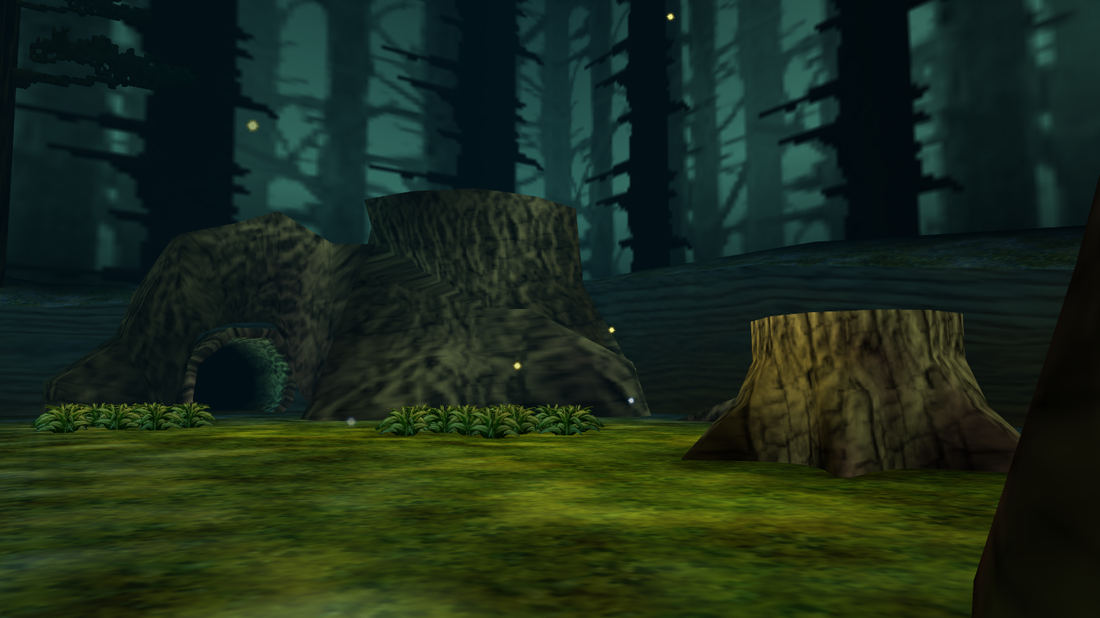

The first feelings are those of confusion, anger, and sorrow. Alone, a young boy on a horse slowly wanders through an uncanny wood of fallow trees and dying light. He searches for a departed friend, the only being that can truly be said to understand him, his past, and his pain. In his quest, though he had triumphed over evil and saved a kingdom, he had lost everything — his land, his youth, and his identity. Following nothing but the orders of a princess and the overwhelming sense of grief that attended the sudden loss of his truest friend, he chases a lingering thought: that reunion is still possible, and that in this meeting he will at last find acceptance, peace, and himself.

Journeying through the distant forest between worlds, he is set upon, in his solitude, by an imp of the Lost Woods: a creature not animated by malice, but a being of childish mischief hearkening back to more carefree days of pranks, youth, and a pleasant land surrounded by bewilderment and peril. In his frustration, deprived of all that was dearest to him, the boy gives chase through the grey vapor of twilight, only to be left alone before a cavernous void in the bole of a tree. Having nothing more to lose, he continues his pursuit, and is led yet deeper into the forest, through groves of fey lighting and blackened trees against a dark sky.

And he falls.

The first feelings are those of confusion, anger, and sorrow. Alone, a young boy on a horse slowly wanders through an uncanny wood of fallow trees and dying light. He searches for a departed friend, the only being that can truly be said to understand him, his past, and his pain. In his quest, though he had triumphed over evil and saved a kingdom, he had lost everything — his land, his youth, and his identity. Following nothing but the orders of a princess and the overwhelming sense of grief that attended the sudden loss of his truest friend, he chases a lingering thought: that reunion is still possible, and that in this meeting he will at last find acceptance, peace, and himself.

Journeying through the distant forest between worlds, he is set upon, in his solitude, by an imp of the Lost Woods: a creature not animated by malice, but a being of childish mischief hearkening back to more carefree days of pranks, youth, and a pleasant land surrounded by bewilderment and peril. In his frustration, deprived of all that was dearest to him, the boy gives chase through the grey vapor of twilight, only to be left alone before a cavernous void in the bole of a tree. Having nothing more to lose, he continues his pursuit, and is led yet deeper into the forest, through groves of fey lighting and blackened trees against a dark sky.

And he falls.

Majora’s Mask takes place only a few months after the ending of Ocarina of Time in the Era of the Hero of Time. After those historied events in Hyrule, Princess Zelda sent Link into exile to prevent Ganondorf from ultimately entering the Sacred Realm and bringing about the cataclysm of the adult timeline. It is this banishment that eventually leads him to the nameless wood and the parallel world of Termina. As Link falls, he obtains a glimpse of the future, though this is yet unknown to him. Unintelligible faces and shapes rise up from beneath him, set against the crackling sound of dead branches in a flame. Landing in an unknown chamber far below the earth, Link is confronted by the now-angry Skull Kid, who hexes Link, throwing him into a waking dream from which he emerges transformed. Reflected in the clear water at his feet, the image of an uncomprehending Deku Scrub gazes back, though the gravity of this transformation is overcome by renewed feelings of vengeance and a need for normalcy. What results from this upwelling of emotion is a feverish chase through a vast underground root system. It is in this fathomless cave complex that we first encounter the terrible truth lying behind the masks of this world. Near the end of the underground path rests the twisted form of a young Deku Scrub, who is now forever bound to this grotesque liminal space, though it is unknown what brought him here, and to what end he came. Still, his body is marked by death, and it is his death that permits Link to travel between identities, and between the worlds of those that yet live and those who once lived. [1]

Passing briefly by this spirit whose form he now bears, the transfigured child continues onward through one last tunnel before emerging underneath the fabled Clock Tower of Clock Town, in the heart of all Termina. As the heavy doors seal behind him, a strange melody floats overhead, permeating the walls, and without a clear source. Ancient gears lie half-buried in this dim room, and a narrow ramp leads through the intricate machinery of this strange mechanism. It is here that Link meets a familiar, though not comforting, face. The Happy Mask Salesman, who before worked from his shop in Hyrule Market, has inexplicably made his way into Termina, and introduces us to one of the first major themes present within this game: that of identity and masking.

On Identity and Masking

“Your true face . . . What kind of . . . face is it? I wonder . . . The face under the mask . . . is that . . . your true face?” — One of the Masked Children

The relationship between these two beings is perhaps the strangest and most intriguing within this game, and, though I know not why, it makes me sad. Both Link and the Happy Mask Salesman have lost something precious to them. And it is this loss that brings them together in the faded dark of an old tower. The Happy Mask Salesman questions Link and enjoins him to retrieve a certain mask that was stolen from him, and, in turn, Link is healed, and taught the Song of Healing, an otherworldly melody which has the power to alleviate, rejuvenate, and calm. We must not forget that, until this point, Link was wearing the face of a dead child. Masks hold the spirits of the dead within this universe, and, in this way, Link is but an extension of the departed; he acts as an agent of change who is often influenced and led by the previous wishes, regrets, and emotions of those he has become. What becomes apparent is this: in order for Link to fully succeed in his quest, saving both a land and its people, he must first face death and dying in all their myriad forms, and then represent each people of Termina by becoming one of their dead. In this way, he gains a transformative power for good through death and the reverence he pays to the parted.

Relatedly, if we decide to analyze the emotional state of Link as he experiences the initial happenings of this game, we come to realize that sadness and grief likely dominated his mind and heart. What friends he had were erased from knowledge by the Ocarina of Time, and what due recognition he deserved was lost. Having only memory, and a few chosen friends who maintained their knowledge of his quest, Link was cast aside into the wilderness, only to lose both Navi and Epona, leaving him utterly alone. Even his identity as a Hylian — which he had only recently discovered — was taken from him, leaving him in an unfamiliar body in an unfamiliar land. And though he found himself with a new companion, Navi was still gone, and the white light of Tatl gave no comfort to ease the sorrow building in his heart. In this manner does the other side of the coin show itself: without a solid sense of identity, what takes its place? When everything — self, mind, and memory — has ceased to exist meaningfully, to what does a child cling? And this is where the game has unmistakable challenges set aside for the thoughtful player. Link does not confront his lack of self immediately, but masks his pain, his confusion, and his suffering in another quest: the quest to find Majora’s Mask. He accepts the demands of an external reality, hoping that something along the way, though in what form he does not dare to dream, will tell him who he is, and why he is. The Happy Mask Salesman, perhaps sensing the deep psychological distress of this child, helps Link, even as he helps himself; he secures his lost item, and Link gains the comforting certainty of something concrete and real: a task. Link is, of course, but a child, and children generally have little experience with questions of the self, but even a child can feel like a non-entity, unwanted, uncared-for, and unsure. It could very well be that this task, this quest, saves his life. Because even though it starts as a series of external immediacies and problems to be solved, each experience which attends his journey is itself a form of spiritual growth. If we here apply some foundational teachings of Buddhism, we find that Link himself may not ever discover a sense of who he is, only because the self, as we view it, does not exist as something above and beyond the changing conditions of the world: and that what really matters is how we confront reality, question both life and death, and work compassionately for others. And, as Link will come to find, these concerns are inescapable.

As with the Hero, these themes and queries are just as necessary for us. If we are thinking, and not simply reacting to the stimuli of the game, we are also confronted by these questions. Who am I? What is this thing that is seeing, hearing, and thinking? To what extent am I my feelings, opinions, and physical makeup? What is this? To forego confronting these questions, as uncomfortable as they are, is to take up complacency, which is the very antithesis of what I believe this game aims at achieving. It is not enough to play the game, and it is not even enough to examine this-or-that aspect of Link: we ourselves must engage with that which is within us, and we must do so now, for when else can we?

Passing briefly by this spirit whose form he now bears, the transfigured child continues onward through one last tunnel before emerging underneath the fabled Clock Tower of Clock Town, in the heart of all Termina. As the heavy doors seal behind him, a strange melody floats overhead, permeating the walls, and without a clear source. Ancient gears lie half-buried in this dim room, and a narrow ramp leads through the intricate machinery of this strange mechanism. It is here that Link meets a familiar, though not comforting, face. The Happy Mask Salesman, who before worked from his shop in Hyrule Market, has inexplicably made his way into Termina, and introduces us to one of the first major themes present within this game: that of identity and masking.

On Identity and Masking

“Your true face . . . What kind of . . . face is it? I wonder . . . The face under the mask . . . is that . . . your true face?” — One of the Masked Children

The relationship between these two beings is perhaps the strangest and most intriguing within this game, and, though I know not why, it makes me sad. Both Link and the Happy Mask Salesman have lost something precious to them. And it is this loss that brings them together in the faded dark of an old tower. The Happy Mask Salesman questions Link and enjoins him to retrieve a certain mask that was stolen from him, and, in turn, Link is healed, and taught the Song of Healing, an otherworldly melody which has the power to alleviate, rejuvenate, and calm. We must not forget that, until this point, Link was wearing the face of a dead child. Masks hold the spirits of the dead within this universe, and, in this way, Link is but an extension of the departed; he acts as an agent of change who is often influenced and led by the previous wishes, regrets, and emotions of those he has become. What becomes apparent is this: in order for Link to fully succeed in his quest, saving both a land and its people, he must first face death and dying in all their myriad forms, and then represent each people of Termina by becoming one of their dead. In this way, he gains a transformative power for good through death and the reverence he pays to the parted.

Relatedly, if we decide to analyze the emotional state of Link as he experiences the initial happenings of this game, we come to realize that sadness and grief likely dominated his mind and heart. What friends he had were erased from knowledge by the Ocarina of Time, and what due recognition he deserved was lost. Having only memory, and a few chosen friends who maintained their knowledge of his quest, Link was cast aside into the wilderness, only to lose both Navi and Epona, leaving him utterly alone. Even his identity as a Hylian — which he had only recently discovered — was taken from him, leaving him in an unfamiliar body in an unfamiliar land. And though he found himself with a new companion, Navi was still gone, and the white light of Tatl gave no comfort to ease the sorrow building in his heart. In this manner does the other side of the coin show itself: without a solid sense of identity, what takes its place? When everything — self, mind, and memory — has ceased to exist meaningfully, to what does a child cling? And this is where the game has unmistakable challenges set aside for the thoughtful player. Link does not confront his lack of self immediately, but masks his pain, his confusion, and his suffering in another quest: the quest to find Majora’s Mask. He accepts the demands of an external reality, hoping that something along the way, though in what form he does not dare to dream, will tell him who he is, and why he is. The Happy Mask Salesman, perhaps sensing the deep psychological distress of this child, helps Link, even as he helps himself; he secures his lost item, and Link gains the comforting certainty of something concrete and real: a task. Link is, of course, but a child, and children generally have little experience with questions of the self, but even a child can feel like a non-entity, unwanted, uncared-for, and unsure. It could very well be that this task, this quest, saves his life. Because even though it starts as a series of external immediacies and problems to be solved, each experience which attends his journey is itself a form of spiritual growth. If we here apply some foundational teachings of Buddhism, we find that Link himself may not ever discover a sense of who he is, only because the self, as we view it, does not exist as something above and beyond the changing conditions of the world: and that what really matters is how we confront reality, question both life and death, and work compassionately for others. And, as Link will come to find, these concerns are inescapable.

As with the Hero, these themes and queries are just as necessary for us. If we are thinking, and not simply reacting to the stimuli of the game, we are also confronted by these questions. Who am I? What is this thing that is seeing, hearing, and thinking? To what extent am I my feelings, opinions, and physical makeup? What is this? To forego confronting these questions, as uncomfortable as they are, is to take up complacency, which is the very antithesis of what I believe this game aims at achieving. It is not enough to play the game, and it is not even enough to examine this-or-that aspect of Link: we ourselves must engage with that which is within us, and we must do so now, for when else can we?

On Friendship, Loss, and Grief

“Your friends . . . What kind of . . . people are they? I wonder . . . Do these people . . . think of you . . . as a friend?” — One of the Masked Children

Led as though by fate, Link emerges into Clock Town on the dawn of the first day, knowing no one nor anything of the place wherein he finds himself. Yet, over the course of three days, he begins to discover the emotional distress hidden but a little below the surface of daily life in this world, and eventually manages to find his way to the top of the Clock Tower, where Skull Kid awaits. Open only one day of the year for the Festival of Time, this place of joy and celebration has now become the focal point of terrestrial demise. As the dialogue plays out, Tatl’s brother, Tael, only now understanding his part in the destruction of his homeland, quickly begs of Tatl and Link: “Swamp. Mountain. Ocean. Canyon . . . Hurry, the four who are there . . . bring them here!” Thus putting aside his fevered thoughts, anguish, and confusion, Link grasps for the fallen Ocarina of Time, plays a portentous song, and initiates the first three-day cycle in this strange new land.

It is here that a critical question demands attention. What drove the Skull Kid, who is naturally mischievous but not bad-hearted, to desire such vengeance, and what precipitated the fall from his childlike past? Perhaps it is best to begin with a story recounted to us by Anju’s grandmother. [2]

“The Four Giants, is it? This is quite long, but it is a good story for you to hear, so I'll read it with some extra gusto. Ahem . . . ‘The Four Giants.’ This tale's from long ago when all the people weren't separated into four worlds like they are now. In those times all the people lived together, and the four giants lived among them.

On the day of the festival that celebrates the harvest, the giants spoke to the people . . . ‘We have chosen to guard the people while we sleep . . . 100 steps north, 100 steps south, 100 steps east, 100 steps west. If you have need, call us in a loud voice by declaring something such as, 'The mountain blizzard has trapped us.’ Or, 'The ocean is about to swallow us.' Your cries shall carry to us . . . .’

Now then . . . There was one who was shocked and saddened by all this.

A little imp.

The imp was a friend of the giants since before they had created the four worlds. ‘Why must you leave? Why do you not stay?’ The childhood friend felt neglected, so he spread his anger across the four worlds. Repeatedly, he wronged all people. Overwhelmed with misfortune, the people sang the song of prayer to the giants who lived in each of the four compass directions. The giants heard their cry and responded with a roar. ‘Oh, imp. Oh, imp. We are the protectors of the people. You have caused the people pain. Oh, imp, leave these four worlds! Otherwise, we shall tear you apart!’ The imp was frightened and saddened.

He had lost his old friends. The imp returned to the heavens, and harmony was restored to the four worlds. And the people rejoiced and they worshiped the giants of the four worlds like gods. And they lived happily . . . ever after . . . .”

Writing about loss and grief is inescapable when speaking of the primary tropes and themes of Majora’s Mask. Many have written on these two subjects and their interconnectedness, some people espousing the universality of Link as a window to healing and loss; as Link moves throughout Termina, helping relieve others of their present suffering, “he becomes a metaphor for anyone confronting grief in any shape or form, when sometimes the only thing a person can do in the face of loss is to move forward. The three-day cycle he relives over and over again throughout the course of the game could be symbolic of the process the grief-ridden face every day; one in which life can become nothing more than endless routine as one works through their pain.” [3] Loss and grief are not everlasting, though, however many times they appear within the course of a life. Reunion and peace are equally important themes at play within the emotional landscape of Termina, perhaps most eloquently chronicled in the story of Anju and Kafei. The separation of these two lovers, about a month prior to their wedding ceremony, initiates one of the longest and most emotionally-fraught side-quests within the Zelda series, “in which the player has moved heaven, earth, and time itself to bring these two lovers back together . . . with nothing left to do except initiate the most poignant reset of all. Just before the moon falls, the player initiates the Song of Time . . . And suddenly, all is as it was before. It's the first day once again, and the boy clothed in a Keaton Mask and blue garb once again races to the postbox just outside the laundry pool, unaware that in another life, he had just been reunited with his true love at last. In that moment, it is never more evident that the only way to end this cycle of emotional misery and death once and for all is to defeat the Skull Kid and restore Termina to a peaceful state.” [4]

Skull Kid had been abandoned by the giants long ago, and, not knowing how best to cope with his confusion and grief, he gave in to anger, and to vengeance. Having lost all the bonds that connected him to others, he then set out to rupture all bonds within Termina: bonds between family, lovers, and friends, bonds between people and their environments, and the bonds connecting order and the absurd. Yet, there is a soft echo that exists between Link and the Skull Kid. Link lost Navi, his dearest friend, and the Skull Kid was left by the Four Giants, believing them to have abandoned him. Dealing with their own grief, they pursued various paths in order to help them understand and cope with the loss. Link chose pursuit, unwilling to let Navi drift away, and the Skull Kid chose ruin, giving in to wrath and retribution, without understanding the true causes of his suffering. And though they did not know it, these two children shared uncannily similar pasts; both were sent from their homes into lands unknown, both were abandoned by their closest friends, and both were left with nothing that would heal, guide, or save them. Their individual paths were poetically similar, yet one divergence in that same path led one child to destroy the world and the other to save it.

Not all partings are permanent, however, and by the end of the game, the paths of these two children converge one last time, but on a conciliatory note. Once separated by their sorrow, they are now united by their experiences, and the profound relief that comes from saving a friendship and healing old wounds. Skull Kid is once again comforted by his friends, and gains an understanding of friendship that is based in selflessness and trust, where before it was a warped reflection compounded by ignorance and greed. And there is something here that is reflective of each person’s childhood: as children, we are by nature self-centered, but as we grow, learn, and find peace in our connections with others, we realize that our happiness is not ours alone, but is also the happiness of others. Likewise, we find true peace in the well-being of our friends and loved ones, and grow all the more because we recognize it as good. In this way, Skull Kid, I think, ultimately finds what he is looking for: familiarity, security, and acceptance. So too does Link gain from his experience. While he still has yet to be reunited with Navi, he has found Epona, and has been bonded powerfully to nearly every being in Termina, even if they do not remember it. So even when Link passes out of their knowledge, he likely takes away with him a heartening fact: the bonds of friendship and of love are both more transcendent and enduring than most people believe. And if this does not give one the strengthened resolve to pursue a missing friend, I am truly at a loss.

“Your friends . . . What kind of . . . people are they? I wonder . . . Do these people . . . think of you . . . as a friend?” — One of the Masked Children

Led as though by fate, Link emerges into Clock Town on the dawn of the first day, knowing no one nor anything of the place wherein he finds himself. Yet, over the course of three days, he begins to discover the emotional distress hidden but a little below the surface of daily life in this world, and eventually manages to find his way to the top of the Clock Tower, where Skull Kid awaits. Open only one day of the year for the Festival of Time, this place of joy and celebration has now become the focal point of terrestrial demise. As the dialogue plays out, Tatl’s brother, Tael, only now understanding his part in the destruction of his homeland, quickly begs of Tatl and Link: “Swamp. Mountain. Ocean. Canyon . . . Hurry, the four who are there . . . bring them here!” Thus putting aside his fevered thoughts, anguish, and confusion, Link grasps for the fallen Ocarina of Time, plays a portentous song, and initiates the first three-day cycle in this strange new land.

It is here that a critical question demands attention. What drove the Skull Kid, who is naturally mischievous but not bad-hearted, to desire such vengeance, and what precipitated the fall from his childlike past? Perhaps it is best to begin with a story recounted to us by Anju’s grandmother. [2]

“The Four Giants, is it? This is quite long, but it is a good story for you to hear, so I'll read it with some extra gusto. Ahem . . . ‘The Four Giants.’ This tale's from long ago when all the people weren't separated into four worlds like they are now. In those times all the people lived together, and the four giants lived among them.

On the day of the festival that celebrates the harvest, the giants spoke to the people . . . ‘We have chosen to guard the people while we sleep . . . 100 steps north, 100 steps south, 100 steps east, 100 steps west. If you have need, call us in a loud voice by declaring something such as, 'The mountain blizzard has trapped us.’ Or, 'The ocean is about to swallow us.' Your cries shall carry to us . . . .’

Now then . . . There was one who was shocked and saddened by all this.

A little imp.

The imp was a friend of the giants since before they had created the four worlds. ‘Why must you leave? Why do you not stay?’ The childhood friend felt neglected, so he spread his anger across the four worlds. Repeatedly, he wronged all people. Overwhelmed with misfortune, the people sang the song of prayer to the giants who lived in each of the four compass directions. The giants heard their cry and responded with a roar. ‘Oh, imp. Oh, imp. We are the protectors of the people. You have caused the people pain. Oh, imp, leave these four worlds! Otherwise, we shall tear you apart!’ The imp was frightened and saddened.

He had lost his old friends. The imp returned to the heavens, and harmony was restored to the four worlds. And the people rejoiced and they worshiped the giants of the four worlds like gods. And they lived happily . . . ever after . . . .”

Writing about loss and grief is inescapable when speaking of the primary tropes and themes of Majora’s Mask. Many have written on these two subjects and their interconnectedness, some people espousing the universality of Link as a window to healing and loss; as Link moves throughout Termina, helping relieve others of their present suffering, “he becomes a metaphor for anyone confronting grief in any shape or form, when sometimes the only thing a person can do in the face of loss is to move forward. The three-day cycle he relives over and over again throughout the course of the game could be symbolic of the process the grief-ridden face every day; one in which life can become nothing more than endless routine as one works through their pain.” [3] Loss and grief are not everlasting, though, however many times they appear within the course of a life. Reunion and peace are equally important themes at play within the emotional landscape of Termina, perhaps most eloquently chronicled in the story of Anju and Kafei. The separation of these two lovers, about a month prior to their wedding ceremony, initiates one of the longest and most emotionally-fraught side-quests within the Zelda series, “in which the player has moved heaven, earth, and time itself to bring these two lovers back together . . . with nothing left to do except initiate the most poignant reset of all. Just before the moon falls, the player initiates the Song of Time . . . And suddenly, all is as it was before. It's the first day once again, and the boy clothed in a Keaton Mask and blue garb once again races to the postbox just outside the laundry pool, unaware that in another life, he had just been reunited with his true love at last. In that moment, it is never more evident that the only way to end this cycle of emotional misery and death once and for all is to defeat the Skull Kid and restore Termina to a peaceful state.” [4]

Skull Kid had been abandoned by the giants long ago, and, not knowing how best to cope with his confusion and grief, he gave in to anger, and to vengeance. Having lost all the bonds that connected him to others, he then set out to rupture all bonds within Termina: bonds between family, lovers, and friends, bonds between people and their environments, and the bonds connecting order and the absurd. Yet, there is a soft echo that exists between Link and the Skull Kid. Link lost Navi, his dearest friend, and the Skull Kid was left by the Four Giants, believing them to have abandoned him. Dealing with their own grief, they pursued various paths in order to help them understand and cope with the loss. Link chose pursuit, unwilling to let Navi drift away, and the Skull Kid chose ruin, giving in to wrath and retribution, without understanding the true causes of his suffering. And though they did not know it, these two children shared uncannily similar pasts; both were sent from their homes into lands unknown, both were abandoned by their closest friends, and both were left with nothing that would heal, guide, or save them. Their individual paths were poetically similar, yet one divergence in that same path led one child to destroy the world and the other to save it.

Not all partings are permanent, however, and by the end of the game, the paths of these two children converge one last time, but on a conciliatory note. Once separated by their sorrow, they are now united by their experiences, and the profound relief that comes from saving a friendship and healing old wounds. Skull Kid is once again comforted by his friends, and gains an understanding of friendship that is based in selflessness and trust, where before it was a warped reflection compounded by ignorance and greed. And there is something here that is reflective of each person’s childhood: as children, we are by nature self-centered, but as we grow, learn, and find peace in our connections with others, we realize that our happiness is not ours alone, but is also the happiness of others. Likewise, we find true peace in the well-being of our friends and loved ones, and grow all the more because we recognize it as good. In this way, Skull Kid, I think, ultimately finds what he is looking for: familiarity, security, and acceptance. So too does Link gain from his experience. While he still has yet to be reunited with Navi, he has found Epona, and has been bonded powerfully to nearly every being in Termina, even if they do not remember it. So even when Link passes out of their knowledge, he likely takes away with him a heartening fact: the bonds of friendship and of love are both more transcendent and enduring than most people believe. And if this does not give one the strengthened resolve to pursue a missing friend, I am truly at a loss.

On Failure and the Path of the Hero

“The right thing . . . What is it? I wonder . . . If you do the right thing . . . Does it really make . . . everybody . . . happy?” — One of the Masked Children

The path of heroism is created of loneliness, exemplified perfectly in this game. For the most part, Link is unable to make friends simply because he is too busy saving them; and these actions, at the end of the three-day cycle, are undone, meaning that, to the citizens of Termina, nothing at all has happened. Link is never recognized for having saved the lives of these people, and, tragically, leaves Termina knowing that their memory of him will simply be of a strange boy who was one day there, and the next, gone. The pain is perhaps made all the more powerful due to the similarities in appearance between the residents of Termina and the people of Hyrule; while they are not the same beings, their appearances bear great similarities, and this strange reminder of home must have an unwelcome effect on the Hero’s quest. [5] And while it seems unfair that the citizens of Termina should forget him, the effects this erasure must have on Link are far worse. Even though Link saves individuals and entire peoples from sorrow and ruin, every time he goes back in time, things revert to before, when they were marked with violence, suffering, distrust, and anxiety. For one so young, this must be both heartbreaking and frustrating; Link must watch as, time and time again, the people that he has grown to care for, and who have helped care for him, fall back into tragedy and distress. Strangely, this cycle can also bring hope. As some have noted, this game focuses primarily upon internal changes; while Termina is trapped interminably in a three-day cycle of grief reborn and suffering unchanged, Link himself grows throughout each cycle, and, “the world is different based only on how he perceives and approaches it.” [6] So, even though the Deku Butler waits anxiously without knowledge of the fate of his son, and Kafei waits without hope for the world’s end, Link progresses along his spiritual path, coming to peace with his own sadness while healing that of others.

Failure is also endemic to Link and his quest. While saving the world, he fails to save some of its people – those beings that help to make Termina what it is. There is simply nothing he can do to save Kamaro, Darmani, and Mikau, no matter how hard he tries or how earnestly he plays the Song of Time. This is a tragic aspect of the nature of heroism — that even world-altering actions can fail to change the personal world of an individual. Keeping a list of many people present in Termina must make this sense of failure more personal; as Link meets these people, he inevitably shares some of their history and pains, and, as Link is the embodiment of courage, he doubtlessly feels somehow responsible for these people and their hardships. He may feel as though he has to save them. Within this game, the paradoxical centrality of side-quests simply proves this point. In our world, heroism is idealized as one of the most beautiful, important, and righteous traits any person can have; to be a hero is to be raised above the common and banal — to exemplify all that is good in humanity. To an extent, this is also the version of heroism we see in many Zelda games, especially within Ocarina of Time. Link is the triumphant hero who, after vanquishing evil and saving the princess, passes once more into his carefree childhood. Or so we are led to believe.

Majora’s Mask shows us a very different side of heroism and its consequences, and it does so powerfully, holding nothing back. Something demonstrated over and over again within this game is that such heroism has a cost. Link is not the only person in Termina who recognizes the impending doom facing the land, and neither is he the only person working to put the world in order. The Deku Princess, sensing the evil in the heart of her kingdom, enters into Woodfall Temple only to be captured by Odolwa; the monkey tries to warn the Deku King of this, but is tortured unjustly; Darmani falls to his death attempting to enter Snowhead Temple and save his people; Mikau is badly beaten and left for dead, floating upon the open water; Romani, without Link’s help, is abducted by phantoms, leaving Cremia to mourn her loss; Tael reveals information about the giants and suffers for this at the hands of the Skull Kid; and even the giants themselves fall prey to the power of Majora’s Mask and are sealed away, unable to fulfill their duties as protectors of the land. While these heroic roles are not all of equal measure or import, each person listed above acted for the betterment of someone else, only to bring greater suffering upon themselves — and this is certainly a more sober, realistic reading of heroism than is normally presented. Heroes may be adored by those they save, but rarely are they understood by those same people.

Also important to note is that each of these heroes ultimately fails, leaving Link to accomplish what they could not, reinforcing Link’s unique status as the True Hero. Should the common narrative prove true, as we expect, then surely Link finally receives his hero’s reward, eventually being reunited with Navi. Yet, at the end of the game, this still has not come to pass, and Link is forced to pursue her even farther into the unknown. As this story shows us so aptly, and so poetically, there are enormous costs that attend the path of heroism, and being a hero has both limitations and consequences.

“The right thing . . . What is it? I wonder . . . If you do the right thing . . . Does it really make . . . everybody . . . happy?” — One of the Masked Children

The path of heroism is created of loneliness, exemplified perfectly in this game. For the most part, Link is unable to make friends simply because he is too busy saving them; and these actions, at the end of the three-day cycle, are undone, meaning that, to the citizens of Termina, nothing at all has happened. Link is never recognized for having saved the lives of these people, and, tragically, leaves Termina knowing that their memory of him will simply be of a strange boy who was one day there, and the next, gone. The pain is perhaps made all the more powerful due to the similarities in appearance between the residents of Termina and the people of Hyrule; while they are not the same beings, their appearances bear great similarities, and this strange reminder of home must have an unwelcome effect on the Hero’s quest. [5] And while it seems unfair that the citizens of Termina should forget him, the effects this erasure must have on Link are far worse. Even though Link saves individuals and entire peoples from sorrow and ruin, every time he goes back in time, things revert to before, when they were marked with violence, suffering, distrust, and anxiety. For one so young, this must be both heartbreaking and frustrating; Link must watch as, time and time again, the people that he has grown to care for, and who have helped care for him, fall back into tragedy and distress. Strangely, this cycle can also bring hope. As some have noted, this game focuses primarily upon internal changes; while Termina is trapped interminably in a three-day cycle of grief reborn and suffering unchanged, Link himself grows throughout each cycle, and, “the world is different based only on how he perceives and approaches it.” [6] So, even though the Deku Butler waits anxiously without knowledge of the fate of his son, and Kafei waits without hope for the world’s end, Link progresses along his spiritual path, coming to peace with his own sadness while healing that of others.

Failure is also endemic to Link and his quest. While saving the world, he fails to save some of its people – those beings that help to make Termina what it is. There is simply nothing he can do to save Kamaro, Darmani, and Mikau, no matter how hard he tries or how earnestly he plays the Song of Time. This is a tragic aspect of the nature of heroism — that even world-altering actions can fail to change the personal world of an individual. Keeping a list of many people present in Termina must make this sense of failure more personal; as Link meets these people, he inevitably shares some of their history and pains, and, as Link is the embodiment of courage, he doubtlessly feels somehow responsible for these people and their hardships. He may feel as though he has to save them. Within this game, the paradoxical centrality of side-quests simply proves this point. In our world, heroism is idealized as one of the most beautiful, important, and righteous traits any person can have; to be a hero is to be raised above the common and banal — to exemplify all that is good in humanity. To an extent, this is also the version of heroism we see in many Zelda games, especially within Ocarina of Time. Link is the triumphant hero who, after vanquishing evil and saving the princess, passes once more into his carefree childhood. Or so we are led to believe.

Majora’s Mask shows us a very different side of heroism and its consequences, and it does so powerfully, holding nothing back. Something demonstrated over and over again within this game is that such heroism has a cost. Link is not the only person in Termina who recognizes the impending doom facing the land, and neither is he the only person working to put the world in order. The Deku Princess, sensing the evil in the heart of her kingdom, enters into Woodfall Temple only to be captured by Odolwa; the monkey tries to warn the Deku King of this, but is tortured unjustly; Darmani falls to his death attempting to enter Snowhead Temple and save his people; Mikau is badly beaten and left for dead, floating upon the open water; Romani, without Link’s help, is abducted by phantoms, leaving Cremia to mourn her loss; Tael reveals information about the giants and suffers for this at the hands of the Skull Kid; and even the giants themselves fall prey to the power of Majora’s Mask and are sealed away, unable to fulfill their duties as protectors of the land. While these heroic roles are not all of equal measure or import, each person listed above acted for the betterment of someone else, only to bring greater suffering upon themselves — and this is certainly a more sober, realistic reading of heroism than is normally presented. Heroes may be adored by those they save, but rarely are they understood by those same people.

Also important to note is that each of these heroes ultimately fails, leaving Link to accomplish what they could not, reinforcing Link’s unique status as the True Hero. Should the common narrative prove true, as we expect, then surely Link finally receives his hero’s reward, eventually being reunited with Navi. Yet, at the end of the game, this still has not come to pass, and Link is forced to pursue her even farther into the unknown. As this story shows us so aptly, and so poetically, there are enormous costs that attend the path of heroism, and being a hero has both limitations and consequences.

On the Absurd and the Familiar

“You . . . What makes you . . . happy? I wonder . . . What makes you happy . . . Does it make . . . others happy, too?” — One of the Masked Children

This incarnation of Link is a being of Hyrule, an established and historied realm of deep legend and knowledge, so when we as gamers descend into the unknown landscape of Termina through him, we feel deeply unsettled. Whereas Hyrule is well-known, almost familiar, to us, it is, “precisely the vagueness surrounding Termina, the lack of lore and explanation, that prevents Majora's Mask from feeling burdened by reality.” [7] Termina is not a second home to many of us who are used to exploring the land of Hyrule, and falling in love with its valleys, rivers, and hills. From the moment this story begins, the mood is dark and unsure, and our first experience of Termina itself is a taste of absurdity: we emerge from beneath the Clock Tower as another being, only to see a sick and grinning moon hanging low in the sky, over a town filled with people who bear the faces of those who we once knew. If Hyrule represents home, Termina is everything that is foreign and strange. In the woods above the world, there is still a semblance of order, and of sanity, but once we go down the rabbit hole into this parallel world, dream logic usurps logic, emotion supplants reason, and the surreal overtakes the real. We experience this story as if in a trance.

Just as the rational and absurd connect, clash, and mix like oil and water in this game, so too do order and chaos. Termina shows all of the signs of having once been an orderly world; there is an established economy, with trade, travel, and tourism, people seem invested in one another, and there is social order and stable government in the four regions. Yet, when Link arrives, the land is in disarray. The swamp is poisoned, the mountains are trapped in perpetual winter, the ocean boils and gives forth strange life, and, in Ikana, the line between life and death itself has become blurred. Even as Link races across the land, in an attempt to set nature aright, he is forced to plunge the world back into chaos each time he begins the cycle of time anew. The poisoned swamp, once saved, is poisoned again; the mountains which briefly saw spring are once again covered in ice and snow. But, in order to achieve lasting order, the world must cycle through disorder repeatedly until, at last, everything is as it should be. There is no victory until the final victory.

Disruption in nature is not the only unraveling to take place in Termina. While the land is thrown into tumult, the ties that bind humanity to one another are severed, leaving a society with a glaring absence of social order. As the moon sinks lower into the sky, the adults of Termina give in to their various neuroses, becoming less and less able to care for themselves and their world; because of this, we, time and time again, see children within this story protecting the adults and setting things right. The relationship that usually exists between adults and the young is completely reversed, so that social order is flipped upon its head. Link, as a child, must uphold order in this strange world, while the adults of the four worlds are seemingly unaware of their situation and are incapable of saving themselves; a young monkey and the Deku Princess are the ones who attempt to save their swamp from the evil within Woodfall Temple, while the Deku King is so trapped in his anger that he cannot see the plight affecting his land; Romani detects the threat of the phantoms, while her older sister fails to believe her; the children of the Bomber Gang have taken on the role of the guards in the city, and while the true guards patrol the four gates, these young boys patrol Clock Town helping others as needed; the Goron Elder’s son must teach Link the song he needs to open the path to Snowhead Temple; Kafei must retie the threads of his life as a child, and not in his adult form; and, lest we forget, even Majora’s Mask seizes a child as his puppet. While the adults fret, ignore, and carry on, the youth of Termina are the ones engaged in its protection, and the fact that they are the primary actors within this story is a sobering reminder that all has been thrown into disarray.

Finally, when we enter into Ikana Valley and see the absolute insanity that holds this land in its grip, we understand that so too have death and life been muddled and warped. The line that usually separates life from death has been broken, and the two realms trespass into one another, allowing the dead to walk where the living fear to tread. Gibdos stalk the landscape, two composers clash in the afterlife over differences they had while living, the castle guards and King of Ikana linger in wrath, and the Garo stalk the dusty paths, unseen, waiting for a master that never came. The only two living beings that yet dwell in this land have nearly passed over, and a daughter is forced to watch as her father slowly transforms into one of the very monsters he intended to study. When we consider that Link must become dead through masking in order to act as an intermediary with many of these phantoms, the fragile line between life and death is shaken yet further. Throughout the entirety of this story, we find that life is not as weak as it seems, and death not as final; people on the verge of collapse transcend their ailments and come again to health, and hungry ghosts still linger, continuing on in the afterlife pursuing those things which shaped their erstwhile lives.

“You . . . What makes you . . . happy? I wonder . . . What makes you happy . . . Does it make . . . others happy, too?” — One of the Masked Children

This incarnation of Link is a being of Hyrule, an established and historied realm of deep legend and knowledge, so when we as gamers descend into the unknown landscape of Termina through him, we feel deeply unsettled. Whereas Hyrule is well-known, almost familiar, to us, it is, “precisely the vagueness surrounding Termina, the lack of lore and explanation, that prevents Majora's Mask from feeling burdened by reality.” [7] Termina is not a second home to many of us who are used to exploring the land of Hyrule, and falling in love with its valleys, rivers, and hills. From the moment this story begins, the mood is dark and unsure, and our first experience of Termina itself is a taste of absurdity: we emerge from beneath the Clock Tower as another being, only to see a sick and grinning moon hanging low in the sky, over a town filled with people who bear the faces of those who we once knew. If Hyrule represents home, Termina is everything that is foreign and strange. In the woods above the world, there is still a semblance of order, and of sanity, but once we go down the rabbit hole into this parallel world, dream logic usurps logic, emotion supplants reason, and the surreal overtakes the real. We experience this story as if in a trance.

Just as the rational and absurd connect, clash, and mix like oil and water in this game, so too do order and chaos. Termina shows all of the signs of having once been an orderly world; there is an established economy, with trade, travel, and tourism, people seem invested in one another, and there is social order and stable government in the four regions. Yet, when Link arrives, the land is in disarray. The swamp is poisoned, the mountains are trapped in perpetual winter, the ocean boils and gives forth strange life, and, in Ikana, the line between life and death itself has become blurred. Even as Link races across the land, in an attempt to set nature aright, he is forced to plunge the world back into chaos each time he begins the cycle of time anew. The poisoned swamp, once saved, is poisoned again; the mountains which briefly saw spring are once again covered in ice and snow. But, in order to achieve lasting order, the world must cycle through disorder repeatedly until, at last, everything is as it should be. There is no victory until the final victory.

Disruption in nature is not the only unraveling to take place in Termina. While the land is thrown into tumult, the ties that bind humanity to one another are severed, leaving a society with a glaring absence of social order. As the moon sinks lower into the sky, the adults of Termina give in to their various neuroses, becoming less and less able to care for themselves and their world; because of this, we, time and time again, see children within this story protecting the adults and setting things right. The relationship that usually exists between adults and the young is completely reversed, so that social order is flipped upon its head. Link, as a child, must uphold order in this strange world, while the adults of the four worlds are seemingly unaware of their situation and are incapable of saving themselves; a young monkey and the Deku Princess are the ones who attempt to save their swamp from the evil within Woodfall Temple, while the Deku King is so trapped in his anger that he cannot see the plight affecting his land; Romani detects the threat of the phantoms, while her older sister fails to believe her; the children of the Bomber Gang have taken on the role of the guards in the city, and while the true guards patrol the four gates, these young boys patrol Clock Town helping others as needed; the Goron Elder’s son must teach Link the song he needs to open the path to Snowhead Temple; Kafei must retie the threads of his life as a child, and not in his adult form; and, lest we forget, even Majora’s Mask seizes a child as his puppet. While the adults fret, ignore, and carry on, the youth of Termina are the ones engaged in its protection, and the fact that they are the primary actors within this story is a sobering reminder that all has been thrown into disarray.

Finally, when we enter into Ikana Valley and see the absolute insanity that holds this land in its grip, we understand that so too have death and life been muddled and warped. The line that usually separates life from death has been broken, and the two realms trespass into one another, allowing the dead to walk where the living fear to tread. Gibdos stalk the landscape, two composers clash in the afterlife over differences they had while living, the castle guards and King of Ikana linger in wrath, and the Garo stalk the dusty paths, unseen, waiting for a master that never came. The only two living beings that yet dwell in this land have nearly passed over, and a daughter is forced to watch as her father slowly transforms into one of the very monsters he intended to study. When we consider that Link must become dead through masking in order to act as an intermediary with many of these phantoms, the fragile line between life and death is shaken yet further. Throughout the entirety of this story, we find that life is not as weak as it seems, and death not as final; people on the verge of collapse transcend their ailments and come again to health, and hungry ghosts still linger, continuing on in the afterlife pursuing those things which shaped their erstwhile lives.

On Dependent Co-Arising

There is a term in Sanskrit called pratītyasamutpāda, which has been translated various ways, from conditioned arising to interdependent origination, and from mutual causality to dependent occurrence. Intellectually, this is not a difficult concept to apprehend. Simplistically, it can be read simply as interconnectedness: the fact that all things are in flux, with each thing affecting others, and being affected in return. Things arise when certain conditions are met, they change, and then cease to be when certain conditions are removed. One of the Three Marks of Existence, this is a fundamental truth according to Buddhism. And like many truths — even those easy to understand — this one is incredibly difficult to realize. For this reason, it will suffice to look at Link’s journey in Termina through the view of interdependence: that nothing can exist unchanged, in isolation.

While this foundational truth applies equally to everything, from the material to the immaterial, it is most visible and pertinent when discussing interpersonal relationships within Termina. And, as humans, it is perhaps the most important aspect to examine, as few things shape our moods, opinions, and lives as much as those around us. In Majora’s Mask, the lives of the characters overlap to a great degree — far more than in any other Zelda title. Because we, through Link, are able to retread lost time, over and over again, these threads of connection become increasingly obvious the more we return to the dawn of the first day. Connections not obvious within the first cycle stand out in the third, and cause and effect become unmistakable by the tenth. With the help of the Bomber’s Notebook, we are able to keep track of individual schedules and map out which people take which path at any given time; with this tool, we are effectively able to see into the future, and this helps us both see and steer causality — which is truly an incredible power to wield.

To understand just how impactful and profound this theme truly is, let us examine the opening chapter of the story that takes place in the Southern Swamp. In order for Link to liberate the people of the swamp from poison and eventual death, many interconnected events must occur. When Link enters the Southern Swamp for the first time, he knows nothing of current happenings. Only by talking to the people within the tourist center and potion shop does he come to learn that one of their companions has gone missing, which leads Link to explore the Woods of Mystery; without interacting with one of the monkeys of this wood, finding Koume is a bitter venture of trial-and-error; unless Link finds Koume and learns that she needs a revitalizing potion, Link is unable to obtain a healing elixir from Koume’s sister, Kotake. Koume’s salvation proves to the monkeys that Link is able to be trusted, and they thus tell Link of their current situation: that one of their kind has been kidnapped by the Deku King. Now that Koume is returned to her post, Link can finally access the other side of the swamp via boat and visit the Deku Palace. This chain of causality continues to describe the heroic actions of the Deku Princess, the poisoning of the swamp, and the eventual defeat of Odolwa and the land’s return to normalcy. Yet, without the seemingly-unimportant rescue of a mushroom-gatherer in the woods, none of this is possible. Each thing affects another, and even the smallest action can determine the fate of a people.

Ikana Valley beautifully demonstrates the relationship between dependent co-arising and the nature of suffering. As things are always changing, arising and ceasing to be, the more we attach ourselves to the world in an attempt to find lasting happiness, the more unhappy we become. And in Ikana, the few living people that exist there are tossed around like so much flotsam, riding out a storm driven by the spirits there that cannot find peace even in death. Two ancient enemies carry on their historied feud, which quietly echoes the more personal feud happening between two once-brothers. In life, Sharp the Elder and Flat the Younger were composers to the court, but eventually became estranged; somehow tricked, Sharp sold his soul to a devil and entrapped his brother beneath the graveyard of Ikana. Now, as ghosts, their actions continue to play out upon the world, shaping the reality of a little girl and her father who make their home in the valley. Sharp’s curse has stopped the flow of the river, which in turn has stopped the water wheel powering the speaker atop the Music Box House; this speaker, which before halted the movements of the Gibdos, has ceased to play, allowing the Gibdos to once again haunt the land. If Link can chase this problem to its source, he finds that the only way forward is to help both Sharp and Flat make the passage into the afterlife. Through music, the curse is lifted, the river flows, and the Gibdos are once again stilled, allowing the little girl to peer hesitantly out of her house. Indirectly, this girl is suffering greatly at the hands of two composers long dead, whose actions affect the entirety of a kingdom. As the days pass, she is forced to watch her father lose his humanity, and drift farther and farther away from her, as he becomes but a shell of his former self. Yet, with Link’s help, he is eventually healed, at least for a time. The two Composer Brothers likely know nothing of this little girl and her father, but they are responsible for her suffering and pain. Even without a direct relationship with one another, these beings are able to cause enormous change and grief in Ikana, which gives us a small glimpse at the true nature of reality: This is, because that is. This is not, because that is not. This ceases to be, because that ceases to be. And nothing is that is without something else.

There is a term in Sanskrit called pratītyasamutpāda, which has been translated various ways, from conditioned arising to interdependent origination, and from mutual causality to dependent occurrence. Intellectually, this is not a difficult concept to apprehend. Simplistically, it can be read simply as interconnectedness: the fact that all things are in flux, with each thing affecting others, and being affected in return. Things arise when certain conditions are met, they change, and then cease to be when certain conditions are removed. One of the Three Marks of Existence, this is a fundamental truth according to Buddhism. And like many truths — even those easy to understand — this one is incredibly difficult to realize. For this reason, it will suffice to look at Link’s journey in Termina through the view of interdependence: that nothing can exist unchanged, in isolation.

While this foundational truth applies equally to everything, from the material to the immaterial, it is most visible and pertinent when discussing interpersonal relationships within Termina. And, as humans, it is perhaps the most important aspect to examine, as few things shape our moods, opinions, and lives as much as those around us. In Majora’s Mask, the lives of the characters overlap to a great degree — far more than in any other Zelda title. Because we, through Link, are able to retread lost time, over and over again, these threads of connection become increasingly obvious the more we return to the dawn of the first day. Connections not obvious within the first cycle stand out in the third, and cause and effect become unmistakable by the tenth. With the help of the Bomber’s Notebook, we are able to keep track of individual schedules and map out which people take which path at any given time; with this tool, we are effectively able to see into the future, and this helps us both see and steer causality — which is truly an incredible power to wield.

To understand just how impactful and profound this theme truly is, let us examine the opening chapter of the story that takes place in the Southern Swamp. In order for Link to liberate the people of the swamp from poison and eventual death, many interconnected events must occur. When Link enters the Southern Swamp for the first time, he knows nothing of current happenings. Only by talking to the people within the tourist center and potion shop does he come to learn that one of their companions has gone missing, which leads Link to explore the Woods of Mystery; without interacting with one of the monkeys of this wood, finding Koume is a bitter venture of trial-and-error; unless Link finds Koume and learns that she needs a revitalizing potion, Link is unable to obtain a healing elixir from Koume’s sister, Kotake. Koume’s salvation proves to the monkeys that Link is able to be trusted, and they thus tell Link of their current situation: that one of their kind has been kidnapped by the Deku King. Now that Koume is returned to her post, Link can finally access the other side of the swamp via boat and visit the Deku Palace. This chain of causality continues to describe the heroic actions of the Deku Princess, the poisoning of the swamp, and the eventual defeat of Odolwa and the land’s return to normalcy. Yet, without the seemingly-unimportant rescue of a mushroom-gatherer in the woods, none of this is possible. Each thing affects another, and even the smallest action can determine the fate of a people.

Ikana Valley beautifully demonstrates the relationship between dependent co-arising and the nature of suffering. As things are always changing, arising and ceasing to be, the more we attach ourselves to the world in an attempt to find lasting happiness, the more unhappy we become. And in Ikana, the few living people that exist there are tossed around like so much flotsam, riding out a storm driven by the spirits there that cannot find peace even in death. Two ancient enemies carry on their historied feud, which quietly echoes the more personal feud happening between two once-brothers. In life, Sharp the Elder and Flat the Younger were composers to the court, but eventually became estranged; somehow tricked, Sharp sold his soul to a devil and entrapped his brother beneath the graveyard of Ikana. Now, as ghosts, their actions continue to play out upon the world, shaping the reality of a little girl and her father who make their home in the valley. Sharp’s curse has stopped the flow of the river, which in turn has stopped the water wheel powering the speaker atop the Music Box House; this speaker, which before halted the movements of the Gibdos, has ceased to play, allowing the Gibdos to once again haunt the land. If Link can chase this problem to its source, he finds that the only way forward is to help both Sharp and Flat make the passage into the afterlife. Through music, the curse is lifted, the river flows, and the Gibdos are once again stilled, allowing the little girl to peer hesitantly out of her house. Indirectly, this girl is suffering greatly at the hands of two composers long dead, whose actions affect the entirety of a kingdom. As the days pass, she is forced to watch her father lose his humanity, and drift farther and farther away from her, as he becomes but a shell of his former self. Yet, with Link’s help, he is eventually healed, at least for a time. The two Composer Brothers likely know nothing of this little girl and her father, but they are responsible for her suffering and pain. Even without a direct relationship with one another, these beings are able to cause enormous change and grief in Ikana, which gives us a small glimpse at the true nature of reality: This is, because that is. This is not, because that is not. This ceases to be, because that ceases to be. And nothing is that is without something else.

On Time and Its Passage

As Sheik told Link in a past life: “Time passes, people move . . . Like a river’s flow, it never ends.” Indeed, the flow of time is inexorable, and the future is inescapable, if experience tells us anything. As mortals, we are bound within time, and no matter our wishes, we are unable to return to moments of regret, either for closure or erasure. And nowhere in life are we able to escape aging, change, and the present. As in our world, the ubiquitous clocks in Termina — which can be found in nearly every room — are a constant reminder of the passage of time, and nowhere is there a more glaring reminder of this fact than in the nomenclature of Termina’s central community. Clock Town sits at the literal center of this land, and the peals of its tower can be heard even in the farthest corners of the world; go where you might, night and day are heralded by the clear sound of bells.

Even while time can be reversed for a short while, it is then only stalled, and not changed; the world is heading toward an undesirable end, and nothing seems possible of changing that fact. Link is always aware of the passing of time, and is even able to control its speed, but in no way is he its master. Like aspects of the natural world, even if we can modify parts of it to suit our needs, it still exists as an entity unto itself, with its own comings and goings. Wherever one goes in Termina, there is an unending discomfort, a dull sense of anxiety, that time is running out.

It seems obvious to state, but we can only ever live in the present. Existing stimuli play upon our senses, calling up thoughts after emotions, feelings after dreams, and plans after journeys to the past. That we are unable to control the mental landscape constantly unfolding within our minds also goes without saying, though we do not always acknowledge this uncomfortable truth. Realizing this, even intellectually, allows us to prevent ourselves a great deal of suffering; when we focus upon the present, instead of dwelling upon the sorrow of the past and the dread of the future, we are able to glimpse the reality of which we are a part, and see that all is more as it should be than we admit. So too with both Link and the Skull Kid. The Skull Kid has been living in the past ever since his perceived abandonment at the hands of his friends, the Giants. Unwilling to accept their reasoning, he refuses to acknowledge his own suffering, and seeks to act upon that betrayal, and is therefore constantly motivated by past anger and sadness. And though he may long for kinder days when all was “as it should be,” the march of time continues, separating him further and further from his own peace and happiness. And the more removed he becomes, the more unhinged he seems. Instead of contemplation, he chooses annihilation, and not just for himself or those who acted against him, but for everyone. When he obtains Majora’s Mask, he is falsely led to the conclusion that he is in fact capable of making it all stop; he will drag the moon from the sky, and destroy Clock Town — its people, their culture, and even time itself. There will be no more clock tower, no more bells, and no more festivals marking the anniversary of his betrayal at the hands of his friends. By demolishing this symbol of time, he not only extinguishes his memories and the memories of all in Termina, but he deprives everyone of present, past, and future.

Link, too, is often held immobile while time flows around him, though this is not of his own choosing. He was bound within the Sacred Realm for seven years during the events prior to his arrival in Termina, sacrificing half of his life for others, and even then he was forbidden from living in the world he helped to save. Having been sent back in time, there was nothing for him. His childhood had been made forfeit by responsibility and separation from his identity and friends, and his adult life was snatched from his hands, leaving him the Hero of Time, yes, but more so a Hero outside of Time, in which the natural flow of time, maturation, and experience had become so blurred as to be meaningless. Even in Termina, Link cannot move forward in life, and is forced to repeat the same three-day cycle again and again. While others live on, completely ignorant of this fact, Link watches the same scenes, hears the same conversations, and bears the weight of a world upon his back, knowing not if the loop will shatter, nor if time will ever again flow on. But, in the end, as Link travels once more through the mysterious wood, the clouds part, and the sun emerges, bathing all in soft light. We know, though, what will become of the Hero of Time. He will never overcome his doubts and regret, and he will succumb to bitterness, even in death.

But, for now, Link watches the peaceful, ignorant people of Clock Town enjoy the Carnival of Time, not realizing or appreciating the power of Time that has given them continued life, nor knowing of the boy who has given them everything. Parting himself at last from this happiness, and from this world, Link steps quietly into one of the shadowy gaps between these stories, and disappears from all our knowledge, until his next incarnation in another age of the earth.

As Sheik told Link in a past life: “Time passes, people move . . . Like a river’s flow, it never ends.” Indeed, the flow of time is inexorable, and the future is inescapable, if experience tells us anything. As mortals, we are bound within time, and no matter our wishes, we are unable to return to moments of regret, either for closure or erasure. And nowhere in life are we able to escape aging, change, and the present. As in our world, the ubiquitous clocks in Termina — which can be found in nearly every room — are a constant reminder of the passage of time, and nowhere is there a more glaring reminder of this fact than in the nomenclature of Termina’s central community. Clock Town sits at the literal center of this land, and the peals of its tower can be heard even in the farthest corners of the world; go where you might, night and day are heralded by the clear sound of bells.

Even while time can be reversed for a short while, it is then only stalled, and not changed; the world is heading toward an undesirable end, and nothing seems possible of changing that fact. Link is always aware of the passing of time, and is even able to control its speed, but in no way is he its master. Like aspects of the natural world, even if we can modify parts of it to suit our needs, it still exists as an entity unto itself, with its own comings and goings. Wherever one goes in Termina, there is an unending discomfort, a dull sense of anxiety, that time is running out.

It seems obvious to state, but we can only ever live in the present. Existing stimuli play upon our senses, calling up thoughts after emotions, feelings after dreams, and plans after journeys to the past. That we are unable to control the mental landscape constantly unfolding within our minds also goes without saying, though we do not always acknowledge this uncomfortable truth. Realizing this, even intellectually, allows us to prevent ourselves a great deal of suffering; when we focus upon the present, instead of dwelling upon the sorrow of the past and the dread of the future, we are able to glimpse the reality of which we are a part, and see that all is more as it should be than we admit. So too with both Link and the Skull Kid. The Skull Kid has been living in the past ever since his perceived abandonment at the hands of his friends, the Giants. Unwilling to accept their reasoning, he refuses to acknowledge his own suffering, and seeks to act upon that betrayal, and is therefore constantly motivated by past anger and sadness. And though he may long for kinder days when all was “as it should be,” the march of time continues, separating him further and further from his own peace and happiness. And the more removed he becomes, the more unhinged he seems. Instead of contemplation, he chooses annihilation, and not just for himself or those who acted against him, but for everyone. When he obtains Majora’s Mask, he is falsely led to the conclusion that he is in fact capable of making it all stop; he will drag the moon from the sky, and destroy Clock Town — its people, their culture, and even time itself. There will be no more clock tower, no more bells, and no more festivals marking the anniversary of his betrayal at the hands of his friends. By demolishing this symbol of time, he not only extinguishes his memories and the memories of all in Termina, but he deprives everyone of present, past, and future.

Link, too, is often held immobile while time flows around him, though this is not of his own choosing. He was bound within the Sacred Realm for seven years during the events prior to his arrival in Termina, sacrificing half of his life for others, and even then he was forbidden from living in the world he helped to save. Having been sent back in time, there was nothing for him. His childhood had been made forfeit by responsibility and separation from his identity and friends, and his adult life was snatched from his hands, leaving him the Hero of Time, yes, but more so a Hero outside of Time, in which the natural flow of time, maturation, and experience had become so blurred as to be meaningless. Even in Termina, Link cannot move forward in life, and is forced to repeat the same three-day cycle again and again. While others live on, completely ignorant of this fact, Link watches the same scenes, hears the same conversations, and bears the weight of a world upon his back, knowing not if the loop will shatter, nor if time will ever again flow on. But, in the end, as Link travels once more through the mysterious wood, the clouds part, and the sun emerges, bathing all in soft light. We know, though, what will become of the Hero of Time. He will never overcome his doubts and regret, and he will succumb to bitterness, even in death.

But, for now, Link watches the peaceful, ignorant people of Clock Town enjoy the Carnival of Time, not realizing or appreciating the power of Time that has given them continued life, nor knowing of the boy who has given them everything. Parting himself at last from this happiness, and from this world, Link steps quietly into one of the shadowy gaps between these stories, and disappears from all our knowledge, until his next incarnation in another age of the earth.

Works Cited:

[1] "The Twilight Realm and the Legacy of the Hero." In The Legend of Zelda: Hyrule Historia, translated by Michael Gombos, 110. Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Books, 2013.

[2] Majora’s Mask. Nintendo. 26 Oct. 2000. Video Game.

[3] Worley, Connor. "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask — A Story About Loss." Talk Amongst Yourselves. January 5, 2015. Accessed December 11, 2015.

[4] Worley, Connor. "Anju's Anguish — The Brilliance of Zelda's Greatest Side Quest." Talk Amongst Yourselves. March 23, 2015. Accessed December 12, 2015.

[5] "Turmoil in the Parallel World of Termina." In The Legend of Zelda: Hyrule Historia, translated by Michael Gombos, 111. Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Books, 2013.

[6] "Hylian Dan” “Immortal Childhood.” Zelda Universe. 14 Sept. 2011. Web. 13 Mar. 2016.

[7] Petit, Carolyn. "In the Mouth of the Moon: A Personal Reading of 'Majora's Mask'" VICE. March 3, 2015. Accessed December 10, 2015.

[1] "The Twilight Realm and the Legacy of the Hero." In The Legend of Zelda: Hyrule Historia, translated by Michael Gombos, 110. Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Books, 2013.

[2] Majora’s Mask. Nintendo. 26 Oct. 2000. Video Game.

[3] Worley, Connor. "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask — A Story About Loss." Talk Amongst Yourselves. January 5, 2015. Accessed December 11, 2015.

[4] Worley, Connor. "Anju's Anguish — The Brilliance of Zelda's Greatest Side Quest." Talk Amongst Yourselves. March 23, 2015. Accessed December 12, 2015.

[5] "Turmoil in the Parallel World of Termina." In The Legend of Zelda: Hyrule Historia, translated by Michael Gombos, 111. Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Books, 2013.

[6] "Hylian Dan” “Immortal Childhood.” Zelda Universe. 14 Sept. 2011. Web. 13 Mar. 2016.

[7] Petit, Carolyn. "In the Mouth of the Moon: A Personal Reading of 'Majora's Mask'" VICE. March 3, 2015. Accessed December 10, 2015.