Gerudo Town and the Great Desert

"Mother . . . Will I ever be as great a chief as you were?"

— Riju, Breath of the Wild

Among the many diverse peoples and races present in Hyrule, the Gerudo have always attracted special attention; they remain a cultural isolate, and because of this inherent separation, they incite the most conspiracy and speculation. The Zelda community takes a deep delight in creating complex theories concerning their origins, evolution through time, and relationship to mainstream Hylian religion, economics, and history. They are also a touchstone for modern critical theory, and people often choose to discuss societal issues of racism, Orientalism, and problems of race and gender as regards the representation of the Gerudo throughout The Legend of Zelda as a series. As with all things fascinating and enduring, the presence of the Gerudo foments a great deal of controversy and opinionation.

While I do not want to make matters political for too long, as this is far from the express purpose of this website, it would be rather shortsighted to overlook how these in-game tropes interface with real-world peoples and their cultures. Breath of the Wild and Ocarina of Time, while being some of the most broadly-praised games in the franchise, are not without their detractors, and much of the tumult almost inevitably focuses around the Gerudo and their representation in the series; and as much of what we know of the Gerudo comes from these two games, these are generally the titles which garner the most controversy. A subset of feminist writers have found the motivations of the Gerudo to be too dependent on men, as if the designers “have immense difficulty conceiving of female characters as independent beings who exist beyond their relationships to men,” and accusing them of creating a “voyeuristic male fantasy that involves violating women’s spaces through deception.” [1] And while one could argue that the invasion of privacy is not unique to women’s spaces (sneaking is an integral part of the Zelda experience, and many times Link must sneak through forbidden spaces in his efforts to save Hyrule — not solely those that belong to women), and that the game itself might not just be about “acting out male fantasies in a virtual world,” there is certainly a conversation to be had here about the conceptualization of women in a self-imposed exile.

— Riju, Breath of the Wild

Among the many diverse peoples and races present in Hyrule, the Gerudo have always attracted special attention; they remain a cultural isolate, and because of this inherent separation, they incite the most conspiracy and speculation. The Zelda community takes a deep delight in creating complex theories concerning their origins, evolution through time, and relationship to mainstream Hylian religion, economics, and history. They are also a touchstone for modern critical theory, and people often choose to discuss societal issues of racism, Orientalism, and problems of race and gender as regards the representation of the Gerudo throughout The Legend of Zelda as a series. As with all things fascinating and enduring, the presence of the Gerudo foments a great deal of controversy and opinionation.

While I do not want to make matters political for too long, as this is far from the express purpose of this website, it would be rather shortsighted to overlook how these in-game tropes interface with real-world peoples and their cultures. Breath of the Wild and Ocarina of Time, while being some of the most broadly-praised games in the franchise, are not without their detractors, and much of the tumult almost inevitably focuses around the Gerudo and their representation in the series; and as much of what we know of the Gerudo comes from these two games, these are generally the titles which garner the most controversy. A subset of feminist writers have found the motivations of the Gerudo to be too dependent on men, as if the designers “have immense difficulty conceiving of female characters as independent beings who exist beyond their relationships to men,” and accusing them of creating a “voyeuristic male fantasy that involves violating women’s spaces through deception.” [1] And while one could argue that the invasion of privacy is not unique to women’s spaces (sneaking is an integral part of the Zelda experience, and many times Link must sneak through forbidden spaces in his efforts to save Hyrule — not solely those that belong to women), and that the game itself might not just be about “acting out male fantasies in a virtual world,” there is certainly a conversation to be had here about the conceptualization of women in a self-imposed exile.

There is also the concept of the Bechdel-Wallace test, which stands as a measure of the representation of women in fiction. And while this test is not without its problems (as much specificity and nuance are thrown out the window in favor of mere box-checking), it may still prove valuable to analyze Breath of the Wild, and especially Gerudo culture, through its lens. There are generally two criteria requisite for a passing grade: that there be at least two women in the work, and they must speak to one another about something other than a man. There is occasionally the third criterion of the women being named. Looking at Breath of the Wild, then, we find that:

None of this is to say that the depiction of the Gerudo as women is perfect in its instantiation; there are nearly always steps that can be taken to make video games more true to the complexities of real life. And this leads us to accusations of Orientalism as crystallized in the Gerudo. Drawing from the tropes of the Middle-east as seen from outside eyes, some worry that the Gerudo in this game are nearly a caricature of a culture: “The Gerudo draw from a variety of orientalist tropes. They're a secretive people with the only foreign language in the game, they wield scimitars (a sword from the Middle East) and they live in a forbidden desert town . . . . As if that weren't enough, the main dungeon for this section of the game is a giant mechanical camel. (Get it? Because camels live in the Middle East.)” [2] Continuing, the author then opines about the unnecessary blending together of cultures and peoples into “vague brown stereotypes”. And this is to some degree true; the Gerudo certainly borrow from many real-world cultures, and Nintendo’s modus operandi has long been about creating the impression of a setting rather than a pure representation of terrestrial art and architecture. To this end, they borrow like magpies and blend like flamboyant impressionists.

There are perhaps certain dangers and injustices that attend any conflation of peoples, and it is quite likely that art and media have a role to play in redressing the damage done by unfair stereotypes; yet these are not the only factors at play, and we must also pay attention to intention and cultural diffusion across time and space. It is unlikely that the developers had disrespect in mind when choosing the scimitar as one of the Gerudo’s chief weapons, and the choice of a camel for the Divine Beast seems, well, an entirely natural choice, given the ecosystem surrounding Gerudo Town. And while it is perhaps a bit over-the-top in terms of obviousness, would a snake or fox have been as striking? Would they have been less controversial? I’m not sure. What I am rather certain of is that the developers and designers do a fair bit of research before they create an in-game civilization, and I can’t imagine that this is driven by spite, although ignorance may certainly play a part. But, again, when choosing a region’s most impactful cultural phenomena to represent and blend, it is to create a thing of beauty, not mockery. What the developers engage in is a sped-up process of cultural diffusion: aspects from one society meet those of another, and through successive generations — blendings of ideas, technologies, art — new creations are born, not formed from nothing, but from the contact of distinct somethings. We can never have knowledge of the end results of cultural diffusion, and any fictional design will be limited of necessity. So the questions remain: is the treatment a fair one? Is it respectful? Does it show beauty? To me, Gerudo Town is one of the most profound and lovely spaces to be found in Breath of the Wild, and its cultural backing is far deeper than the inspirations behind most of the Hylian settlements. And, to me, this speaks not of irreverence but of an enduring respect.

- There are certainly more than two women, and with the imbalance of Gerudo society taken into account, it is likely that the women in Hyrule outnumber the men. (We must also remember that Hylian soldiers were largely men, and because of the utter collapse of the Hylian Army during the time of the Calamity, the population is likely even more skewed because of this.)

- While there are certainly some women in this game, even among the proud and independent Gerudo, who mention little other than their desire for men, it would be unfair to categorize that as the majority of woman-to-woman speaking; many of the cutscenes (which comprise the bulk of such interactions) depicting the three most prominent Gerudo figures — Riju, Buliara, and Urbosa — fail to mention men even once. Instead, they are focused upon saving the realm from chaos. So while it may be true that many of the less-important Gerudo exploring the Hyrulean landscape are on a quest to find a man, it remains inaccurate to say that most of the game is dominated by such speech; just as many women are concerned about travel-writing or securing a business for their wares. (And as important and critical as love and coupling are in life, it would be distinctly odd if no one were to mention their desires toward the opposite sex.)

- Due to the larger detailing of the Gerudo language in Breath of the Wild, we are given the names of each and every character we meet. No longer are we met by “Guard” or “Shop Owner”. There are roughly sixty Gerudo women living in or around Gerudo Town, and many others navigating the larger world, and each of them is given a unique name.

None of this is to say that the depiction of the Gerudo as women is perfect in its instantiation; there are nearly always steps that can be taken to make video games more true to the complexities of real life. And this leads us to accusations of Orientalism as crystallized in the Gerudo. Drawing from the tropes of the Middle-east as seen from outside eyes, some worry that the Gerudo in this game are nearly a caricature of a culture: “The Gerudo draw from a variety of orientalist tropes. They're a secretive people with the only foreign language in the game, they wield scimitars (a sword from the Middle East) and they live in a forbidden desert town . . . . As if that weren't enough, the main dungeon for this section of the game is a giant mechanical camel. (Get it? Because camels live in the Middle East.)” [2] Continuing, the author then opines about the unnecessary blending together of cultures and peoples into “vague brown stereotypes”. And this is to some degree true; the Gerudo certainly borrow from many real-world cultures, and Nintendo’s modus operandi has long been about creating the impression of a setting rather than a pure representation of terrestrial art and architecture. To this end, they borrow like magpies and blend like flamboyant impressionists.

There are perhaps certain dangers and injustices that attend any conflation of peoples, and it is quite likely that art and media have a role to play in redressing the damage done by unfair stereotypes; yet these are not the only factors at play, and we must also pay attention to intention and cultural diffusion across time and space. It is unlikely that the developers had disrespect in mind when choosing the scimitar as one of the Gerudo’s chief weapons, and the choice of a camel for the Divine Beast seems, well, an entirely natural choice, given the ecosystem surrounding Gerudo Town. And while it is perhaps a bit over-the-top in terms of obviousness, would a snake or fox have been as striking? Would they have been less controversial? I’m not sure. What I am rather certain of is that the developers and designers do a fair bit of research before they create an in-game civilization, and I can’t imagine that this is driven by spite, although ignorance may certainly play a part. But, again, when choosing a region’s most impactful cultural phenomena to represent and blend, it is to create a thing of beauty, not mockery. What the developers engage in is a sped-up process of cultural diffusion: aspects from one society meet those of another, and through successive generations — blendings of ideas, technologies, art — new creations are born, not formed from nothing, but from the contact of distinct somethings. We can never have knowledge of the end results of cultural diffusion, and any fictional design will be limited of necessity. So the questions remain: is the treatment a fair one? Is it respectful? Does it show beauty? To me, Gerudo Town is one of the most profound and lovely spaces to be found in Breath of the Wild, and its cultural backing is far deeper than the inspirations behind most of the Hylian settlements. And, to me, this speaks not of irreverence but of an enduring respect.

When Edward Said published his monumentally-influential Orientalism in 1978, his basic thesis focused upon Western conceptualization of “the East”. Said held that Western opinions and scholarship were largely “biased and projected a false and stereotyped vision of ‘otherness’ on the Islamic world that facilitated and supported Western colonial policy.” [3] When Westerners looked toward the East, they saw peoples frozen in amber: static, exotic, and strangely lovely in a certain light. Because of their unchanging and fixed nature, when compared with Western dynamism they were necessarily seen as backward and in need of external motivation towards civilizational cultivation and education. And it was during these centuries — of imperial and colonial rule — that many of the common Orientalist tropes were imported into European media. Images of “the East” play out endlessly in Western media, from children’s TV shows to the most profound works of literature. Do the Gerudo bear out some of these tropes? Certainly. But it is currently an unknown as to why these elements were chosen over others. And like Said’s controversial work, there is a discussion to be had concerning the shadow of Orientalist tropes in Breath of the Wild — and about the nature of tropes in general. [4]

And while all of these discussions should be given proper space and respect, I do think that there is a distinctly modern obsession with conflating little moments of oversight or overt bigotry with the larger representation as it stands — as if a moment can mar a masterpiece. Some have spoken out against the shallowness and callous nature of Link’s adoption of the Gerudo clothing, finding the sidequest to obtain it marked by “negative connotations” [5] and a “disdainful stance toward [trans people’s] existence”. [6] It is certainly true that Vilia, the character who gives Link his Gerudo clothing, is treated in an ambivalent manner — shown as poised and assertive, yet ultimately the butt of a joke. As I have said, the game, even as an overall triumph in many ways, including many aspects of social justice, is not without its flaws. But while there are a few that take Nintendo wholly to task for failures of representation or smuggling in harmful ideologies (some with overt axes to grind [7]), there are yet others that treat the game with nuance, praising the game for its attempt “to represent a strong, proud matriarchal society”, while still finding fault with the game for not going far enough in questioning and subverting aspects of Gerudo culture. [8] And where would we be without such a rich discussion concerning these matters of contemporary cultural importance?

And while all of these discussions should be given proper space and respect, I do think that there is a distinctly modern obsession with conflating little moments of oversight or overt bigotry with the larger representation as it stands — as if a moment can mar a masterpiece. Some have spoken out against the shallowness and callous nature of Link’s adoption of the Gerudo clothing, finding the sidequest to obtain it marked by “negative connotations” [5] and a “disdainful stance toward [trans people’s] existence”. [6] It is certainly true that Vilia, the character who gives Link his Gerudo clothing, is treated in an ambivalent manner — shown as poised and assertive, yet ultimately the butt of a joke. As I have said, the game, even as an overall triumph in many ways, including many aspects of social justice, is not without its flaws. But while there are a few that take Nintendo wholly to task for failures of representation or smuggling in harmful ideologies (some with overt axes to grind [7]), there are yet others that treat the game with nuance, praising the game for its attempt “to represent a strong, proud matriarchal society”, while still finding fault with the game for not going far enough in questioning and subverting aspects of Gerudo culture. [8] And where would we be without such a rich discussion concerning these matters of contemporary cultural importance?

At last moving on from the issues of the real world, we can turn to the Gerudo and their culture. And when viewing a culture, it behooves us to look also at cultural values and how they are borne out, inculcated, and supported by societal structures. Of all the peoples of Hyrule, the Gerudo have spent the longest time in civilizational isolation, having “. . . their own unique language and, because they are a society isolated by a vast desert, their own deeply rooted culture and customs.” [9] The Gerudo are fascinating for a host of reasons, but the most interesting, and inexplicable, fact is that they produce only one male once every hundred years. Because they bear only female offspring but for this centennial phenomenon, the Gerudo are simultaneously one of the most independent and dependent cultures in Hyrule. The massive gender imbalance has created a culture with an intensely singular relationship towards males in every area of life; largely skeptical of men, and almost completely autonomous of them, the Gerudo are yet dependent upon them for their very existence. And though in the past they allowed men to assume the throne, we know that there have been no male leaders since the appearance of the Gerudo King who eventually became the Calamity. [10] After this time, the Gerudo became led by chiefs who passed on the crown matrilineally. So while the Gerudo remain an intensely separate and sovereign people, they cannot escape the odd facts of their unique biology — an anomaly which is at the heart of their society, and likely permeates every facet of Gerudo life, interaction, and value.

Perhaps the most crystallized statement of Gerudo philosophy comes from Urbosa, who relates that the “. . . Gerudo have no tolerance for unfinished business”. And while this is a very straightforward and explicit statement of Gerudo pragmatism and focus on action, we can also see it in the structuring of Gerudo society — particularly in its economy. Simply put, and leaving aside any judgment, there is undoubtedly a huge and deeply-rooted capitalistic strain among the Gerudo: not only do they value task completion (“finished business”), but they are incredibly business-oriented. [11] The Gerudo set up shop most everywhere they can find, and they leave Gerudo Town primarily for two reasons (which can be seen as the two guiding motivations of Gerudo exploration) — trade and partnership. A walk through Gerudo Town shows instantly the diversity of their commercialism and the depth of their talents in finding and selling new commodities; there are four competing general stores, two Sand-Seal rental locations, a hotel, canteen, and specialty shops for arrows, fashion, jewelry, and even black-market armor. Outside of Town, Kara-Kara Bazaar is full of merchants hawking wares, and, as has been stated before, half of the Gerudo traveling Hyrule seem to be in search of economic opportunity.

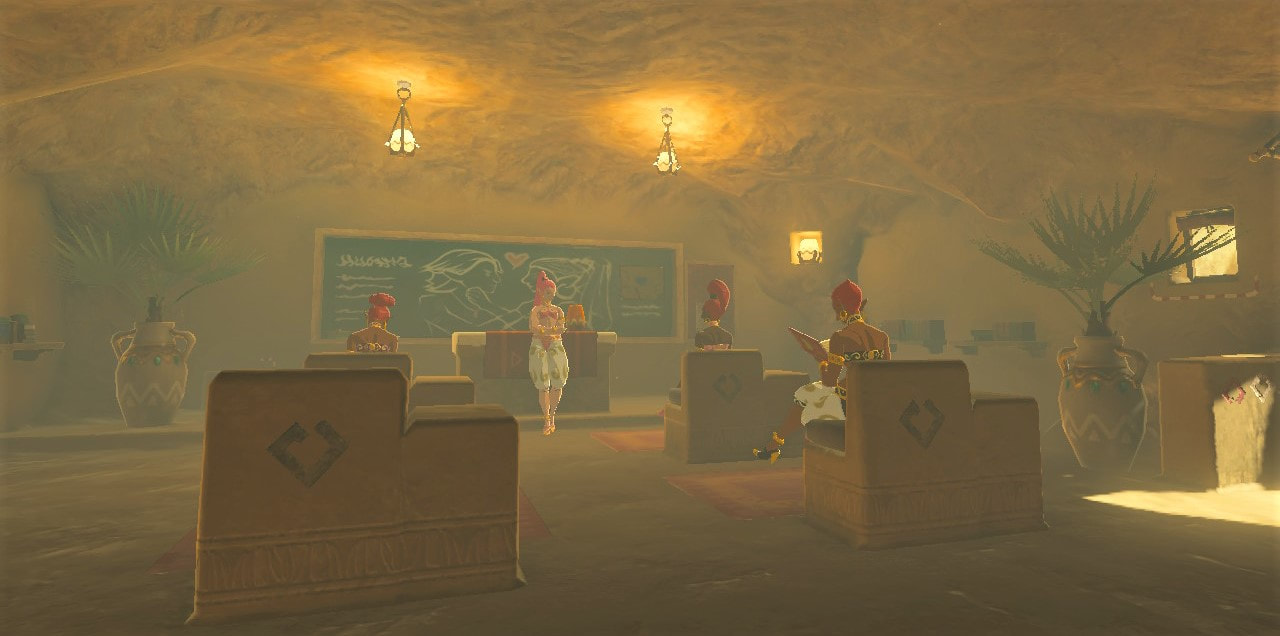

This search for new business partners often coincides with the slightly-absurd search for romantic partners, even though “the Gerudo have held onto a belief that if young Gerudo women interact with men it will bring disaster” since ancient times; and once the women complete their courtship journey, having quite literally courted disaster according to Gerudo adage, they largely return to Gerudo Town in order to make money. [12] Another strange paradox in Gerudo mate-seeking is this: nearly every Gerudo woman desires a relationship with a Hylian mate, clearly bounded within Hylian relational norms (hence the existence of a school teaching traditional romance tactics centered around “the Voe of the world”), and yet they simultaneously look upon the Hylians with no small amount of condescension. [13] The Gerudo praise themselves rightly as tough, resourceful, and powerful; they are universally respected as warriors, and all of their valorous qualities can also make them a bit arrogant, creating relationships founded partly on shifting sands. The Gerudo must find suitable mates, but they first need to overcome or ignore their long-standing view that holds non-Gerudo males to be comically inept or laughably weak. [14] Love is always an emotionally-complex pursuit, and out of the two reasons for Gerudo travel, it is far and away the more difficult quest. There are many things working against successful coupling, not to mention more intensive relationships like marriage, which make events like the marriage of Rhondson and Hudson in Tarrey Town all the more endearing.

Perhaps the most crystallized statement of Gerudo philosophy comes from Urbosa, who relates that the “. . . Gerudo have no tolerance for unfinished business”. And while this is a very straightforward and explicit statement of Gerudo pragmatism and focus on action, we can also see it in the structuring of Gerudo society — particularly in its economy. Simply put, and leaving aside any judgment, there is undoubtedly a huge and deeply-rooted capitalistic strain among the Gerudo: not only do they value task completion (“finished business”), but they are incredibly business-oriented. [11] The Gerudo set up shop most everywhere they can find, and they leave Gerudo Town primarily for two reasons (which can be seen as the two guiding motivations of Gerudo exploration) — trade and partnership. A walk through Gerudo Town shows instantly the diversity of their commercialism and the depth of their talents in finding and selling new commodities; there are four competing general stores, two Sand-Seal rental locations, a hotel, canteen, and specialty shops for arrows, fashion, jewelry, and even black-market armor. Outside of Town, Kara-Kara Bazaar is full of merchants hawking wares, and, as has been stated before, half of the Gerudo traveling Hyrule seem to be in search of economic opportunity.

This search for new business partners often coincides with the slightly-absurd search for romantic partners, even though “the Gerudo have held onto a belief that if young Gerudo women interact with men it will bring disaster” since ancient times; and once the women complete their courtship journey, having quite literally courted disaster according to Gerudo adage, they largely return to Gerudo Town in order to make money. [12] Another strange paradox in Gerudo mate-seeking is this: nearly every Gerudo woman desires a relationship with a Hylian mate, clearly bounded within Hylian relational norms (hence the existence of a school teaching traditional romance tactics centered around “the Voe of the world”), and yet they simultaneously look upon the Hylians with no small amount of condescension. [13] The Gerudo praise themselves rightly as tough, resourceful, and powerful; they are universally respected as warriors, and all of their valorous qualities can also make them a bit arrogant, creating relationships founded partly on shifting sands. The Gerudo must find suitable mates, but they first need to overcome or ignore their long-standing view that holds non-Gerudo males to be comically inept or laughably weak. [14] Love is always an emotionally-complex pursuit, and out of the two reasons for Gerudo travel, it is far and away the more difficult quest. There are many things working against successful coupling, not to mention more intensive relationships like marriage, which make events like the marriage of Rhondson and Hudson in Tarrey Town all the more endearing.

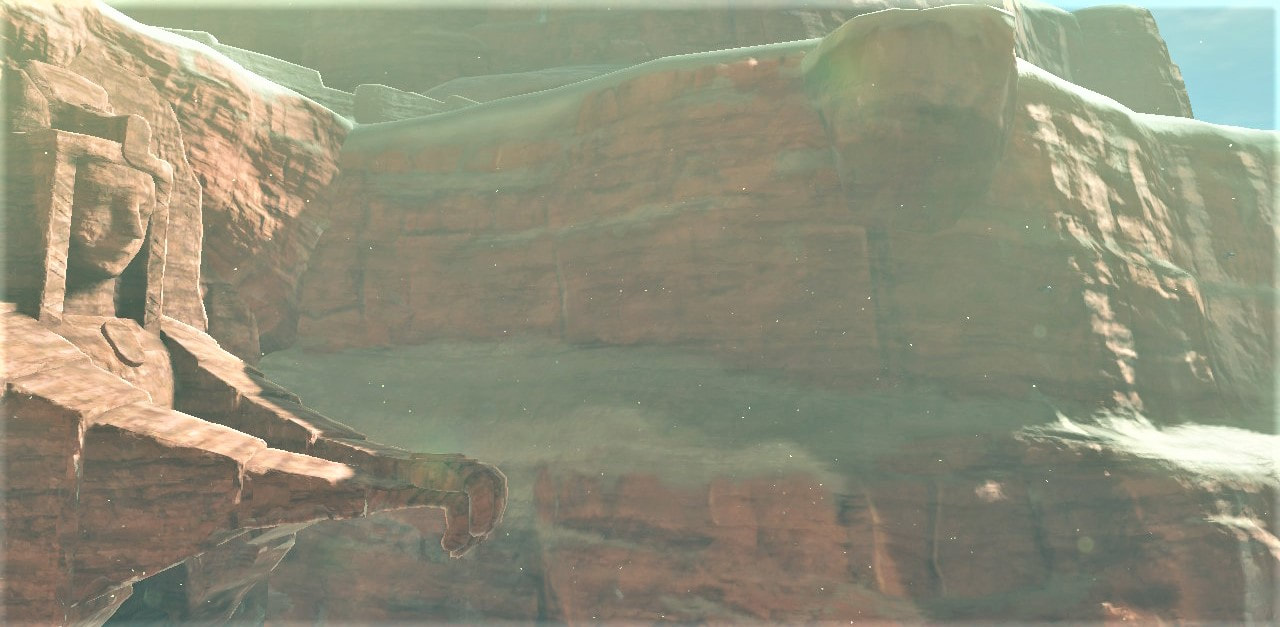

We can take present Gerudo society as relatively unchanged, as the Guardians’ assault on Hyrule did not reach their lands. And this is not surprising, as the desert is one of the most remote and difficult-to-reach places in all the world. The Gerudo Canyon leads into the desert — notably the only entrance to Gerudo territory — where platforms can be seen on every cliff-face, as these were once the excavation sites that eventually led to the discovery of the Divine Beast Vah Naboris a century ago. From this canyon, entry to the desert flows through the Gerudo Desert Gateway, which is a large gate of stone that demarcates the beginning of the desert. Because of the natural boundaries to their land, and considering the heat, scarcity of water, and the territorial nature of the Molduga, it is easy to imagine how such an insular and unique culture came into being, and how they have maintained such singular forms and patterns of being over the ages. With all trade, immigration, and visitation channelled through one easily-guarded entrance, solely on the terms of the Gerudo, it is clear how and why “The Gerudo have always been a people apart . . . .” They play on their own terms, or not at all.

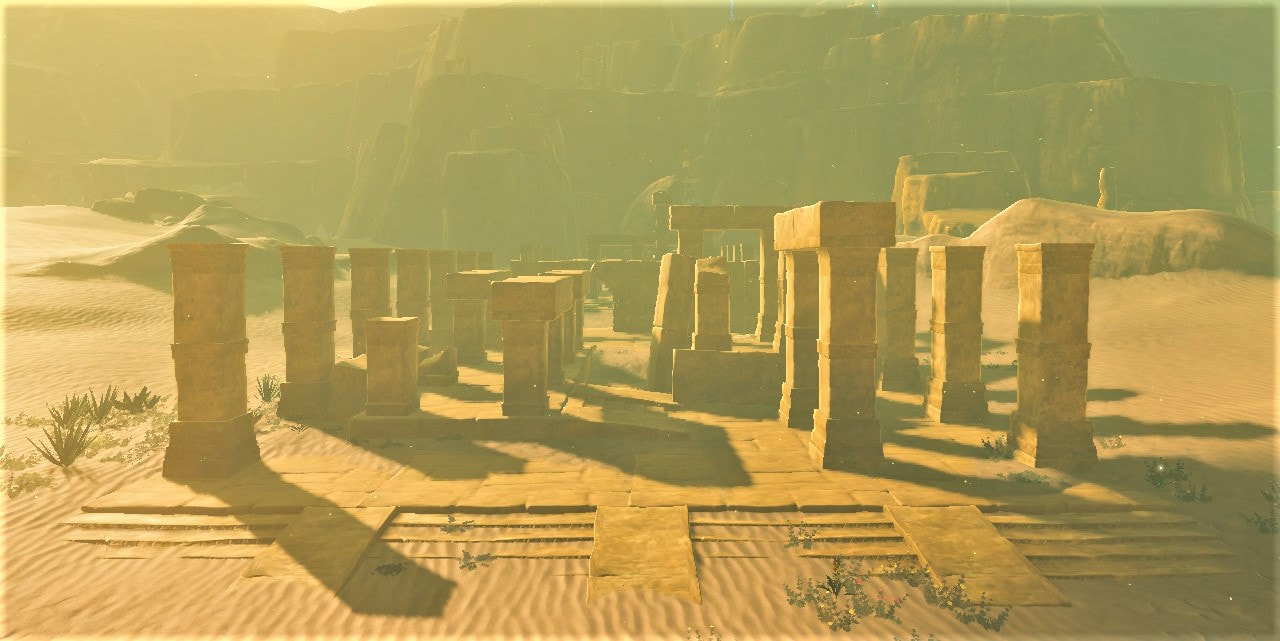

Gerudo Desert is immense. It stretches for many days’ and nights’ journey in every direction, and is punctuated at times by various landmarks both natural and artificial; among the lands of Hyrule it is marked by the most drastic changes in temperature — as night turns to day, and as we descend from mountain peak to desert floor — and in topography. Amid the undulating, sun-baked dunes are found mesas, plateaus, oases, and the feet of mountains; here too are plants both life-giving and threatening, and creatures both skittish and deadly. And among the rolling hills and solitary cacti are countless ruins built by the Gerudo or their ancient predecessors. Some remains are in fairly good condition, while others are little more than time-worn pillars left to decay in the lone and level sands. [15] Barrens are noted on the map, though little remains in those areas, drawing more attention to the relatively complete — and therefore more recent, in likelihood — vestiges, like the West and East Gerudo Ruins, as well as the massive unnamed complex to the direct north of Gerudo Town.

Gerudo Desert is immense. It stretches for many days’ and nights’ journey in every direction, and is punctuated at times by various landmarks both natural and artificial; among the lands of Hyrule it is marked by the most drastic changes in temperature — as night turns to day, and as we descend from mountain peak to desert floor — and in topography. Amid the undulating, sun-baked dunes are found mesas, plateaus, oases, and the feet of mountains; here too are plants both life-giving and threatening, and creatures both skittish and deadly. And among the rolling hills and solitary cacti are countless ruins built by the Gerudo or their ancient predecessors. Some remains are in fairly good condition, while others are little more than time-worn pillars left to decay in the lone and level sands. [15] Barrens are noted on the map, though little remains in those areas, drawing more attention to the relatively complete — and therefore more recent, in likelihood — vestiges, like the West and East Gerudo Ruins, as well as the massive unnamed complex to the direct north of Gerudo Town.

These ruins were built by the ancient predecessors of the Gerudo, about whom we know virtually nothing. Rather unsurprisingly, they hearken back to the archetypal desert architecture of the imagination: that of an Egypt long past. It should first be noted, from an orientational standpoint, that the two older complexes (the western and central ruins) run on a north-south axis, whereas the newer construction, Gerudo Town, runs northeast to southwest. This is an intriguing difference. While temples in Egypt were not all oriented in a similar manner, most were based on an east-west axis and focused on the central axis used for ceremonial procession. And while much of these buildings, like their real-world counterparts, have fallen into disrepair, we can still read important facts in their remains. Like many Egyptian temples dedicated to deities, we can see the rough make-up of these Gerudo structures as having a similar division into outer courtyards, a central grand hall, and several private inner chambers dedicated to priests and holy functions. While most of the ceilings have caved in or disappeared entirely, there are still some surviving lintels which connect the blocky columns together, and even faint pictographs can be seen carved into the stone.

|

The rough profile of these columns can be divided into four parts: the base, shaft, capital, and architrave (the chief beam resting atop the capitals). The base, which rests atop a plinth, is rectangular in shape, and tapers upward, bearing three bands: the first and third bands marked by a triangular geometric design which are separated by a plain inner band. From there, the shaft of the column is shaped of brick and plaster and divided by another band bearing pictographs which can barely be made out. The capital is simple, again carved with the angular designs seen on the base, while the architrave is quite plain: a solid sandstone panel which suspends heavier stone blocks. Much of the decoration of this temple has likely disappeared with sun and weather, and the fact that anything is left to us is, frankly, miraculous; much like Egyptology, the past comes to the surface in shambles, and meaning-making is a nearly impossible task.

|

The Swordswomen statues are directly related to these older structures, being housed across the desert in architectural settings just like these ancient temples. They stand on square plinths with sturdy, yet flowing bodies; each carries a small buckler held in the left hand as a symbol of protection, while the right arm is held aloft in line with the statue’s gaze. A sword is raised in defiance, pointing toward the horizon. In this stance, we can glean both protection and warfare — a visual representation of Gerudo strength and tenacity. The faces are highly angular, and each woman has her hair pulled back into a tight ponytail. Because these Swordswomen have their own particular orientation in the desert, creating a winding path toward one of the ancient shrines of the Sheikah that dot the land, they break with the focused axes of the other two temple structures, exchanging celestial meaning for a more exact religious purpose.

Here we should take a detour into Gerudo religious traditions, as they vary quite distinctly from the worship of Hylia present everywhere else in Hyrule. For while the Gerudo too have their statue to Hylia in Gerudo Town, it is relegated to an out-of-the-way alley, tucked amidst junk-heaps and swept with dust rolling in off the desert. As one of the Gerudo nearby states, “. . . the Goddess Statue has been here since before I was even born. No one here really believes in that stuff anymore, though, so they tend to avoid stopping here." [16] It seems, based on this comment, that Hylia used to be an object of devotion and spirituality, but, for the moment, the Gerudo have their eyes pointed to a different pantheon — one which enshrines Gerudo values in monumental form. While the smaller Swordswomen trace lines across the desert, their larger counterparts stand vigil in the East Gerudo Ruins, a holy place and past site of pilgrimage for people around the world: those who would risk the desert for the blessing of the heroines. [17] These divine protectors and patron deities, shaped in seven monumental sculptural figures and arrayed around a common point, each possessed a different power in Gerudo lore; each Heroine held a respective trait: skill, spirit, endurance, knowledge, flight, motion, and gentleness. [18]

The mythical Eighth Heroine, dismissed by most Gerudo as a fairy tale, stands high in the Gerudo Highlands, separated from her sword in an eternal lonely vigil. What power she governed is likely to remain a mystery. Yet these Heroines all share a bond: Rotana, the archaeologist of the Gerudo, reveals that, “the heroines held powers that were part of a bigger whole.” [19] What exactly this means is unclear, but it is quite obvious that these Heroines all combine to crystallize Gerudo values, and the values of survival in a hard place — the necessity of skill, endurance, knowledge, and, most striking of all, gentleness. This Heroine-worship bears a relationship with the medieval concept of the Nine Worthy Women, the later female addition to the Nine Worthies: nine legendary men who embodied various aspects of the chivalric ideal. Like their male counterparts, the Lady Worthies were culled from scripture and history, legends and myths; and like the men, they too were often displayed in poses of martial might — conquerors of both lands and personal vices. While the Nine Worthy Women were less fixed in composition than the Nine Worthies, some common personages included Hippolyta, Thamarys, and Penthesilea. (Interestingly, two of these women were queens of the Amazonians, a connection to the Gerudo which should not go overlooked by the careful reader.)

Caption: A medieval fresco graces the walls of the onetime castle Castello della Manta in Saluzzo, Italy. (Giorgio Majno/Fondo Ambiente Italiano); Source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/travel/fossano-italy-is-the-perfect-hub-for-exploring-the-lush-piedmont-region/2014/03/13/0d156b96-a0bf-11e3-b8d8-94577ff66b28_story.html

These seven statues were likely once bounded by an immense cliff wall of stone, out of which they were carved (partially or wholly). There are remnants of this wall still supporting the statues from behind, and thick structural walls can yet be seen in the approach from the desert’s southern and western paths. This wall, as we can see, was carved partially of stone and filled in with brick and mortar, likely covered by lime or plaster and decorated by the three bands seen earlier at the base of the temple columns. These statues all face inward toward a central shrine, and the back of each statue is flat, likely carved away from the natural stone, while the front of each statue depicts a woman wearing a headdress and robe, with sand-worn chest, feet, hands, and sword. From their feet stretch seven elongated stone pathways which taper toward the center where they terminate in circular openings — ringed in Gerudo script reading “Pedestal” — for the Ancient Spheres of the Sheikah. There are tiers of scaffolding and bright lamps on several of the statues, likely signalling either excavation or maintenance. Most of the statues are relatively intact, but some have lost key features. Yet, perhaps the most fascinating feature remains: along the hems of the Heroines’ robes can be read, in Gerudo, “The Seven Sages” — an interesting connection to the Seven Sages of the Hylians.

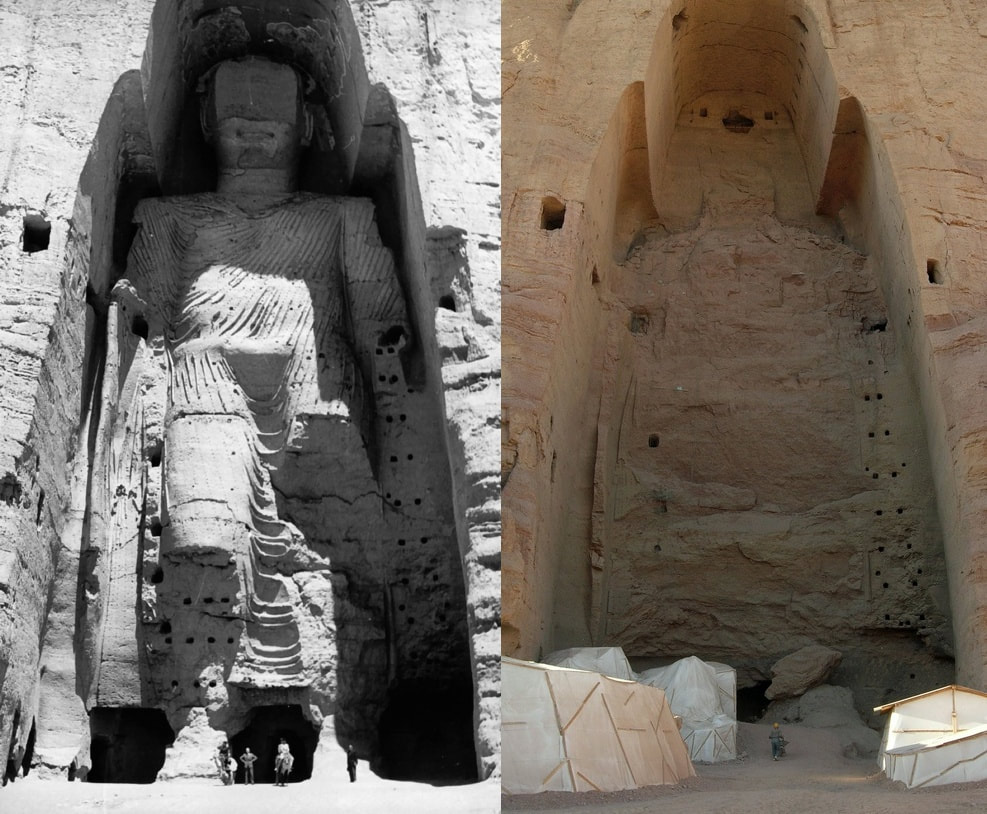

Like the Gerudo themselves, who have forms inspired by Buddhist statues found throughout India and China, their architecture too seems to spring from the Silk Road, from East Asia to the Middle East. [20] The most obvious connection that one can draw between these statues and any human creation is to the Buddhas of Bamiyan [21], so ignominiously dynamited in 2001 by the Taliban. Carved into the cliffs of Bamiyan in Afghanistan, the two statues of the Vairocana and Shakyamuni Buddhas once stood at 115 and 174 feet in height (35 and 53 meters, respectively), making them, for centuries, the largest depictions of the Buddha in existence. Shaped in the 6th century, these statues once represented a prime example of Greco-Buddhist art, as religious imagery from the East met with the classical forms of the West; their bodies were sculpted directly from the sandstone cliffs by which they eventually came to be overshadowed, and like these statues of the heroines were at least partially modeled with other materials. And while the feet of the Buddha have been partially recrafted, their ultimate fate — both controversial and cost-prohibitive — is unknown. [22]

Like the Gerudo themselves, who have forms inspired by Buddhist statues found throughout India and China, their architecture too seems to spring from the Silk Road, from East Asia to the Middle East. [20] The most obvious connection that one can draw between these statues and any human creation is to the Buddhas of Bamiyan [21], so ignominiously dynamited in 2001 by the Taliban. Carved into the cliffs of Bamiyan in Afghanistan, the two statues of the Vairocana and Shakyamuni Buddhas once stood at 115 and 174 feet in height (35 and 53 meters, respectively), making them, for centuries, the largest depictions of the Buddha in existence. Shaped in the 6th century, these statues once represented a prime example of Greco-Buddhist art, as religious imagery from the East met with the classical forms of the West; their bodies were sculpted directly from the sandstone cliffs by which they eventually came to be overshadowed, and like these statues of the heroines were at least partially modeled with other materials. And while the feet of the Buddha have been partially recrafted, their ultimate fate — both controversial and cost-prohibitive — is unknown. [22]

Above Left: Buddha_Bamiyan_1963.jpg: UNESCO/A Lezine;Tsui at de.wikipedia.Later version(s) were uploaded by Liberal Freemason at de.wikipedia.Buddhas_of_Bamiyan4.jpg: Carl Montgomeryderivative work: Zaccarias [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

The last thing to be said about these divine symbols of the Gerudo relates to an older archaeological site found within the Yiga Clan’s hideout. At the top of a narrow canyon, and serving as the secretive antechamber to the Yiga complex, is a room surrounded by eight Gerudo statues. If indeed these are representations of the same heroines as they seem to be, it should be very intriguing as to why there are eight represented here, and only seven without. And while the faces are masked in this chamber, we can still see many important similarities in design between these statues and their larger counterparts farther away in the desert. The swords are similar in their rough design, although they differ in proportion and in the statues’ grip on their individual hilts. So too are these women adorned differently, both in fabric and style of dress. Lastly, the headdresses appear very different, the seven having a more pharaonic headdress with a cartouche, while these eight have a design that hails from farther east. The similarity between the headwear is that both feature an oval at the center above the forehead; whether this is merely a symbol of authority or a representation of the all-seeing eye is unknown. And while these differences seem great, we must remember that they are only slight (yet critical in terms of art history) modifications.

These statues are clearly related to one another, and it is likely that time and style provide the answer as to their dissimilarities. The seven appear to have been crafted with greater skill (in their angles and curves, in the detailing on the swords and raiment, and in the ability of the sculptors to use negative space to separate the arms and sword from the body — especially on such a scale), but these eight appear in far better condition, being cleaner of line and showing a greater uniformity and consistency of design and production. (This could also be due to the fact that they exist in a sheltered cave, not exposed to the elements, but this is a relatively moot point.) The key thing to be discovered here is: which came first, and which inspired the other? It is difficult to glean because their environs (and the effects of their environs) are so different, and may have erased all conclusive evidence.

And there is one further statue which must be considered, as well, and it presides over the barracks next to the royal palace in Gerudo Town. It is an exact copy of those statues found in the Yiga cave, though its features and engravings have been fully worn away. Like the Eighth Heroine high in the mountains, this statue is completely isolated from its sister-statues, and its existence is a puzzle. Above all, I am left wondering: why this recurring motif of an exiled heroine? If the canonized number of Heroines is seven, why is there an eighth in the mountains, and why are there eight within the Yiga hideout? Furthermore, why is this statue overlooking the Gerudo training yard? Perhaps she is simply the Heroine who overlooks one of the Gerudo values related to military training — likely Skill or Endurance. Nothing concerning these statues is clear, however, and even without a definitive statement, their presence is fascinating, and the unknowns of the Gerudo religion shine with a greater magnetism because of it.

These statues are clearly related to one another, and it is likely that time and style provide the answer as to their dissimilarities. The seven appear to have been crafted with greater skill (in their angles and curves, in the detailing on the swords and raiment, and in the ability of the sculptors to use negative space to separate the arms and sword from the body — especially on such a scale), but these eight appear in far better condition, being cleaner of line and showing a greater uniformity and consistency of design and production. (This could also be due to the fact that they exist in a sheltered cave, not exposed to the elements, but this is a relatively moot point.) The key thing to be discovered here is: which came first, and which inspired the other? It is difficult to glean because their environs (and the effects of their environs) are so different, and may have erased all conclusive evidence.

And there is one further statue which must be considered, as well, and it presides over the barracks next to the royal palace in Gerudo Town. It is an exact copy of those statues found in the Yiga cave, though its features and engravings have been fully worn away. Like the Eighth Heroine high in the mountains, this statue is completely isolated from its sister-statues, and its existence is a puzzle. Above all, I am left wondering: why this recurring motif of an exiled heroine? If the canonized number of Heroines is seven, why is there an eighth in the mountains, and why are there eight within the Yiga hideout? Furthermore, why is this statue overlooking the Gerudo training yard? Perhaps she is simply the Heroine who overlooks one of the Gerudo values related to military training — likely Skill or Endurance. Nothing concerning these statues is clear, however, and even without a definitive statement, their presence is fascinating, and the unknowns of the Gerudo religion shine with a greater magnetism because of it.

|

Above: the Heroine statues as found in the Yiga Cave. Although the stone composition is different, the pose is an exact copy of that statue found in the barracks of Gerudo Town.

|

Left: the Heroine statue overlooking the Gerudo training yard.

Above: the Heroine statuary group found at the Eastern Gerudo Ruins. |

Outside Gerudo Town, to which we eventually must come, as everything in the desert, are four more areas governed by the Gerudo: the Gerudo Lookout Post, Kara Kara Bazaar, the Sand Seal Rally, and the Northern Ice House. Most simple in design is the small observation post slightly south of Gerudo Town. Here the soldier Sudrey was tasked with keeping watch over the Divine Beast Vah Naboris, and, after Vah Naboris finally took its perch atop the mountains to the north, to monitor the activity of monsters in the area. A solitary job in a solitary place, and there is a certain beauty to that. The observation post sits upon a squat mesa — a single room built under a massive boulder. It sits in a crown of natural stone, naturally sheltered from blowing winds and, thanks to the immense rock above it, the heat of the sun. Wooden ladders attached to a series of wooden posts lead upward to the observation deck, and ropes bind the structure together, keeping it flexible in the harsh winds, yet sturdy enough to support onlooking sentinels. Flags flutter high in the air above alongside a windmill (which, if it powers something, reveals nothing), and a draping cloth overhangs the observation platform, protecting those within from harm. As one Gerudo intimates, these cloths also serve to lessen erosion due to the high winds and blowing sands.

Nearer to Gerudo Town is the Sand Seal Rally, largely an unmarked meeting place for racing fans and competitors to engage in the hullabaloo surrounding the sport that has cropped up around the favorite animal of the Gerudo. And it is a simple affair, basically two wooden posts which carry several colorful Gerudo flags and which demarcate the starting line of the competition. This traditional sport of the Gerudo involves surfing behind the animals in a timed race through markers placed in the desert; and while Sand-Seal racing is put on hold during the tumult of Vah Naboris, Link is eventually able to calm the beast and set his sights on the current record holder, Tali. Sand Seals are animals native to the Gerudo Desert Gateway, and are incredibly sensitive to sound, meaning that in order to capture, tame, and eventually domesticate them was likely no easy process. As Link comes to know, approaching and momentarily riding a Sand Seal is not obviously simple, and the animals are notoriously flighty around strangers. So the power these animals hold in Gerudo culture is outstanding compared to the other creatures of the desert: they are a major component of business, transportation, and sport, and some Gerudo, like their chief, Riju, have even taken some as pets. Some are even thought to be oracular. [23] The Rally, then, honors both the competitive nature of the Gerudo and one of their most sacred animals.

Nearer to Gerudo Town is the Sand Seal Rally, largely an unmarked meeting place for racing fans and competitors to engage in the hullabaloo surrounding the sport that has cropped up around the favorite animal of the Gerudo. And it is a simple affair, basically two wooden posts which carry several colorful Gerudo flags and which demarcate the starting line of the competition. This traditional sport of the Gerudo involves surfing behind the animals in a timed race through markers placed in the desert; and while Sand-Seal racing is put on hold during the tumult of Vah Naboris, Link is eventually able to calm the beast and set his sights on the current record holder, Tali. Sand Seals are animals native to the Gerudo Desert Gateway, and are incredibly sensitive to sound, meaning that in order to capture, tame, and eventually domesticate them was likely no easy process. As Link comes to know, approaching and momentarily riding a Sand Seal is not obviously simple, and the animals are notoriously flighty around strangers. So the power these animals hold in Gerudo culture is outstanding compared to the other creatures of the desert: they are a major component of business, transportation, and sport, and some Gerudo, like their chief, Riju, have even taken some as pets. Some are even thought to be oracular. [23] The Rally, then, honors both the competitive nature of the Gerudo and one of their most sacred animals.

The Northern Icehouse, managed by Anche, is both north of Gerudo Town and the massive complex of the ancient Gerudo. Roughly shaped like a turtle, the structure itself actually rests underground where the temperature is cooler. The behemoth construct atop seems, strangely enough, to have been intentionally crafted: boulders have been stacked up with the behemoth boulder propped up on top of them. A series of ladders leads upward toward a wooden lookout tower — quite roughshod — tied together with rope. The wooden platform is shielded from the sun by more cloth, and two flags bearing the Gerudo symbol top the structure. This is another vantage point by which the Gerudo survey and control their territory. Yet the real treasure rests beneath, protected by a trap-door structure of wood and dried grass, held open by weighted chains and a simple crank system.

|

Under this trapdoor a staircase is cut into solid sandstone, leading downward into a dark and cool room dominated by a pool of water. Ice is brought from the Gerudo Highlands, taken to this room, cut into large blocks, and then delivered to Gerudo Town based on need. For instance, all the drinks served at the Noble Canteen are made with the ice sheltered here. Anche is always on guard, and the placement of her “room” (really a small carved hollow in the wall by the staircase) ensures that she is on hand at the entrance in case of intrusion.

Right: The turtle-esque construct which houses the Icehouse. Above: Anche's bed; Right: A view of the pool and ice storage area

|

Other natural and geographic properties lend themselves to the construction of this place: cool water flows in through the back wall, creating a pool where the ice is presumably stored at some point, and its nearness to the highlands means that the ice need only travel a short distance into the desert. From this pool, a wooden ramp leads onto dry land, where ice is stored both on beds of straw and in alcoves dug into the walls. Once here, the ice blocks are separated from one another by dried grass to prevent them from freezing together. On the wall is an armamentarium of Anche’s industry: ice hooks, picks, hammers, and other basic tools that form the foundation of her trade. We might note that, interestingly, ice is a luxury to the Gerudo, once again showing that their economic development is among the most highly sophisticated in Hyrule.

Kara Kara Bazaar, whose name is an etymological delight [24], is the last place on our journey to Gerudo Town. This forum of trade centers on a small oasis on the path to the main settlement of the Gerudo, ringed in palms and a series of tents. Here men are free to do business with the Gerudo, not being allowed in the town itself, which creates an interesting atmosphere in the bazaar. In addition to being a place of free trade, it is also a resting stop, cool enough to not trigger heat effects in game. The desert has three larger oases in total, and the focal point of this caravansary is the beautiful and limpid pool resting at the heart of its ringing palm trees. Here, many travelers seem content to simply sit on the shoreline and watch the light change upon its surface. Nestled among the palms are the merchants’ tents, busy with boxes, ropes, and rugs. Even with the cooler temperature of this oasis, shade is still valuable real-estate, and the merchants hide in the shadows of their tents, placing their goods on wooden boards along the pathway around the water. The merchants’ traveling gear is largely earth-tone in color, marked with triangles and other angular designs. Some of the tents seem to have seen years of use, becoming highly sun-faded, their colors slowly disappearing. They all share a similar design, with a large post of wood buried slightly in the earth and then lowered onto the shipping crates forming the back wall of each shop. Rocks brace this pole, as well, and it is this post which gives the tents their rooflike appearance. Stakes hold down the larger cloth of each tent, though no cloth is large enough to cover everything each saleswoman carries around; it is like a too-small shirt desperately pulled down over a stomach just a bit too large.

The inn is the most arresting structure in the bazaar, partially sculpted from naturally-formed rock, and partially built by stacked stone and something resembling adobe. It is an odd, yet charming, juxtaposition of what man and nature can create together. A massive, precarious boulder overhangs the inn, propped up by a thin chimney of stone, and several large pieces of cloth are hung from it, denoting that it serves some function. The windows are small cuts in the adobe walls, and are marked only by a simple stone lintel. Inside, the light is dim, yet golden, as the shades on the windows allow in only a hazy afternoon sun. We can see here what will be true of most of the buildings of the Gerudo: that each building is both of natural stone and carefully-applied adobe. The floors, like the ceiling, are rough, though some amount of polish has lent them a light sheen not present on any of the other surfaces. Beds and shelves are hollowed into the adobe, supported further by wooden boards and brackets. The hominess of this location is a wonderful microcosm of the splendor we will soon see in Gerudo Town. While most surfaces are shades of brown, they are augmented by colorful stones and paints, and the key interior design feature of the Gerudo is in textiles. Their rugs, blankets, pillows, and wall-hangings lend a healthy warmth to what would otherwise be little more than a cave. Yet anyone spending time in this inn would have a very difficult time in thinking Gerudo architecture amounted to little more than that.

Gerudo Town is the jewel of the desert, both a place of inherent physical beauty and cultural refinement. It was placed upon what is perhaps the most important feature in their region of the world: the largest oasis in the desert. To understand how a civilization thrives is to understand how it relates to its sources of water — and this is especially important for a civilization which has its roots in the desert. Without a protected supply, one is vulnerable, and it is clear that the people who control the water have the power. In Gerudo Town, the main spring was, at some past point, elevated to a position high above the throne room. This is undeniably a manifest symbol of power for a leader, and something that Nintendo sought to achieve in their architectural design. The designers state: “Water was a key design element. Controlling the source of the water in the desert is symbolic of authority. We thought about the relationship between the city’s layout and its water, which led to deciding to place the water source, which was likely discovered by the ancestors of the Gerudo, behind the throne and have it flow into the city as a symbol of the ruler’s authority.” [25] To have life burble up from above one’s throne and from there to flow to one’s people is to seem omnipotent. There is a deep psychological and religious connection then drawn between a ruler and the source of life — both take on a new aspect of divinity, and to go against the throne is therefore to oppose life itself. We can see a powerful mythology coming to pervade the Gerudo Throne, and given these powerful symbols it should not surprise us. From this high spring, the water flows through channels atop the town’s buildings, eventually settling into wells and watering holes. But the water does not simply serve a hierarchical function. “The rooftop waterways help regulate the temperature, making the buildings warmer during the cold nights and cooler during the hot days, which makes living there more tolerable.” [26] Gerudo Town is therefore transformed into a desert paradise — a walled garden. And the garden, with its flowing waters and verdant greenery, has long been a symbol of life and power in desert cultures.

Around 5000 BCE irrigation transformed human agricultural practices forever and also made possible the concept of the garden. Inarguably the Hanging Gardens of Babylon — one of the traditional Seven Wonders of the Ancient World — are among the most historied and fabled gardens in human memory. The gardens themselves, somewhat like the water gardens of the Gerudo, “may have been laid out on the roof of the king’s palace, or perhaps occupied a series of terraces on a giant ziggurat overlooking the Euphrates.” [27] The key difference between these two is that the water gardens of the Gerudo flow constantly from a spring high above the city, whereas the water of the Gardens of Babylon needed to be lifted from the river and underground wells by human artifice (Archimedes’ Screw is mentioned in the ancient texts of King Sennacherib). [28] But, we can note two key similarities between these gardens: that the gardens are at least partially placed atop the royal palace and that they comprised a series of channels across many terraces. It is perhaps surprising that hanging gardens were not solely a Babylonian phenomenon: “Hanging gardens (the first was probably at Nineveh) were at once luxurious, labor-intensive amenities, fortified pleasure parks and potent symbols of power — and very impressive they must have appeared seen from miles away across the desert sands. They were also stocked with exotic plants and animals from the far corners of the empire, offering further proof of the vastness and variety of the sovereign's realms.” [29] All these descriptors ring true also for the Gerudo — from the luxury of their colorful waterways to their city, rising as a symbol of power seen from across the desert.

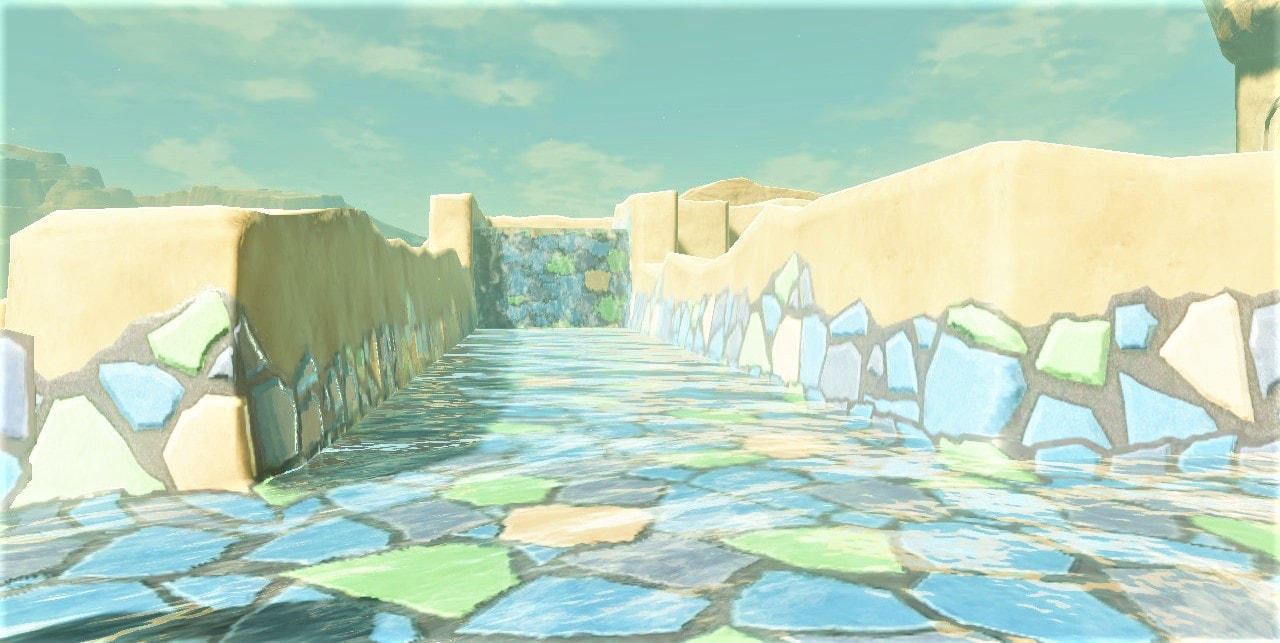

Above: the waters pour down from atop the royal palace and from there are channeled throughout the city in colorful canals.

Gerudo Town is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the largest trading town in all of Hyrule, and its royal palace “is both symbolically and literally a landmark. In terms of game design, having this visual landmark and enclosing the town within walls was necessary to differentiate it from the surrounding desert.” [30] As we see its tiered stone columns rising from the desert sands, we eventually come to see high walls enwrapping the city, marked only by three open archways. The outer walls were carved into the existing stone of the city, and the rock of these walls was also used to construct the buildings — we can see the lighter additions made from adobe in between the darker stone. The wall is, at parts, fitted around large protrusions of rock which have been carved into flat faces, making a structure that is both of nature and against it. Noticeably, the gateways lack any form of permanent gate, and only a few soldiers guard each entrance; furthermore, there are no guards posted atop the walls or at any other lookout point within the city. And while there are two such outposts at a distance away from the town (to the south and north), we can imagine that the Gerudo feel rather secure given the essence of their environment. The main gate is designed after a ziggurat or step-pyramid in image, with an aperture at the top which frames different scenes based upon perspective. Above the main archway is a large Gerudo symbol supported by many colored stones. A brown line of rocks stretches just below the symbol, and, outlining the arch, as well as crowning it, is a span of pastel stones — purple, green, blue, and beige — rough cut and rough placed. It is uncertain whether they are naturally this color, painted, or dyed. In the end, however, the effect is marvelous, and this juxtaposition of color against sand makes this aspect of Gerudo architecture remarkable. Two hollows on either side of the gate hold lamps, and these lamps extend through the massive hallway under the wall, beneath hanging cloths fluttering in a dry wind.

The city itself is magnificent: a series of low buildings under jeweled streams, with a large central courtyard and marketplace dotted with lines of palm trees. Awnings and lean-tos hug the walls of this interior court, where merchants gather to sell their goods, lending color to the dry stone. Most of the town consists in stores and rental shops, but there are also schools dedicated to love and the feminine arts, as well as a bar and inn. As we saw earlier, when we enter into most buildings we see that the roofs are of natural stone and the walls of adobe, adorned with rugs and hanging textiles. Yet, like hobbit holes, these are not mere caves, for the lamps put within yield an amber glow to the air, casting gentle shadows on walls and ceiling. Colorful stones accent angles cut into the adobe, and warm woods form shelves and hanging boards upon which jewelry is hung. These buildings are made homey through the incorporation of potted plants, bright ceramics, books, and woven baskets. The level of artistry and artisanship among the Gerudo is high, and the utter transformative effect that these skills have in Gerudo design cannot be overstated or overlooked.

The streets are clean, for the most part, though small piles of sand build up slowly along the walls, and here and there are set piles of bags and boxes — tell-tale signs of Gerudo merchantry. Water flows from on high into small pools and wells around the city, and everywhere the monotony of sandstone is broken by Gerudo brilliance and craftswomanship. And the peak of Gerudo artistry is unquestionably the royal palace and barracks. From the central courtyard a large staircase is bounded by a channel of softly-flowing water on each side; two Gerudo stand guard at the top of the stairs, while a magnificent arch (such as that seen coming into town) denotes the palace entrance. Another stair leads into the throne room, which simply must be one of the most magnificent chambers in all of Hyrule. Open to the air and framing breathtaking scenes of the Gerudo Desert, the throne room, like all Gerudo structures, achieves its balance between the natural and the engineered. A ceiling of rough stone has been framed by crafted stone walls, pillars, and archways, dotted and adorned with colorful stones, and below it run shallow rivers through grooves in the floor.

Two staircases lead upward to the chief’s bedchamber, and two imposing statues of Gerudo Swordswomen frame the petitioner’s view of the throne. A red carpet runs straight to the dais, a four-posted platform which sits as an island in the middle of the chamber. Lamps cast their light upon the surface of the water, and winds creep in from the massive opening behind the throne. It is clear that the elements have been mastered, and that the chief is at the metaphorical center of the desert — a being whose right is in accordance with nature. Reinforcing this theme, we see gold, precious stones, and other trappings of power dispersed throughout the room: framing the dais and pedestals, serving as the armor for the statues, adorning the capitals of the columns, and, most exquisitely, ground into powder and painted into the Gerudo script carved into throne and pillars. There can be no doubt that the ruler of the Gerudo wields massive regional power and is not to be trifled with. And so it is all the more strange that the chief is but a young child.

Taking the outside stair up to the bedroom above, we quickly see the counterbalance to the opulence and regality below. Reflecting aspects of the chamber beneath this one, there are still archways and flowing water, but these aspects are made less harsh by Riju’s abiding love of the Sand Seal. The waters that flow through her bedroom are channeled through Sand Seal fountainheads, and no small number of Sand Seal stuffed animals are scattered about the furniture. And yet there are still remnants of her mother: a wall with three tall shelves filled with books, large hanging tapestries heavy with age, and a stele set into a highly-stylized alcove in the room bearing reminders of the Gerudo way of life. Gerudo writing can be found engraved throughout the palace complex, from the lamp pedestals which read both “Gerudo” and “Vigilant” to the statue pedestals which read “Gerudo” and “Desert Sun” — a constant parallel of the people to that which sustains them. Columns and fountains also carry these sets of words, but the tall columns, throne, and stele reveal the most poetic renditions of Gerudo creativity.

|

We stand

Vigilant In the Desert sun. We are Brilliant, Over Everyone. |

Gerudo

A resilient Desert flower, Facing the Sun’s gaze. Gerudo grows Brilliant, While others Fade. |

Vigilant

In the sun, Growing Brilliant. Gerudo, Never outdone. |

My lasting impressions of the Gerudo are, in the end, highly favorable. I think the artistic team behind their cultural embodiment rendered a civilization that is as respectful to the Gerudo as it is to the real-world cultures that inspired it. They are truly a people apart: harsh yet gentle, infinitely complex, and as representative of the human spirit as any people to be found in Hyrule. As we take our parting view of the desert, one of the most featureless regions in Breath of the Wild, I am struck by the importance of light in any artistic representation of the desert. In the absence of vivid colors, verdant woodlands, or massive promontories, light is that which gives beauty to the sands. It casts shadows, creating shapes and forms of darkness among the dunes; it instills the air with the clear blue of noon and the gentle lavender of dusk; and it drives life underground only to draw it out again at night. And there is nowhere in Hyrule that affords a better sunset than the mountains overlooking the desert.

Notes and Works Cited:

[1] Cox, Susan. “The New Zelda Video Game Is Improved, but Can't Escape the Industry's Princess Problem.” Feminist Current, 19 Apr. 2017, www.feministcurrent.com/2017/04/18/new-zelda-video-game-improved-cant-escape-industrys-princess-problem/.

[2] Khosravi, Ryan. “'Zelda,' 'Overwatch' and the Failure to Represent Middle Eastern and South Asian Identities in Games.” Mic, 28 June 2017, www.mic.com/articles/179466/zelda-overwatch-middle-eastern-and-south-asian-identities-in-games.

[3] Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Edward Said.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 21 Sept. 2019, www.britannica.com/biography/Edward-Said#ref661781.

[4] Tropes are, by their nature, common reiterations found in media. Yet this does not mean that they are necessarily bad, or even necessarily stale. It does not seem obvious to me that the choice of a scimitar for the Sword of the Seven (Urbosa’s famous blade) is either tiresome or insensitive. Something tells me that a katana would have seemed out of place in Urbosa’s hand, and that a capybara would have made a rather ridiculous Divine Beast; these are not good solely because they fly in the face of what is expected. Within Orientalism, there is a spectrum of representation, from the realistic to the imagined, and we cannot say that because something is an orientalist trope, it is therefore an evil.

[5] Alexandra, Heather. “Despite Nintendo's Stumbles, Breath of the Wild's Fans Have Embraced Crossdressing Link.” Kotaku, Kotaku, 23 Jan. 2018, https://kotaku.com/despite-nintendos-stumbles-breath-of-the-wilds-fans-ha-1793269690.

[6] Unkle, Jennifer. “How Breath of the Wild Failed Us When It Comes To Trans Identity.” Pastemagazine.com, 9 Mar. 2017, https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2017/03/how-breath-of-the-wild-failed-us-when-it-comes-to.html.

[7] I have a lot of problems with this piece of writing, but I think it does summarize some things well, and it does bring up many interesting points of discussion. But, as with all ideologically-driven scholarship, it is intensely myopic and oftentimes infantile in its assertions, conjectures, and the reading of data:

Kimball, Byron J. (2018) “The Gerudo Problem: The Ideology of The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time,” PURE Insights: Vol. 7, Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/pure/vol7/iss1/5

[8] While the author of this piece does make some good points, I can’t help but disagree with a few things that appear driven out of a political expediency that seems to expect that all art be political (an idea which I find a bit reprehensible). Games can tackle cultural and societal issues, but oftentimes these things are not at the forefront of a game’s desired image. More often, video games offer windows into larger events, and when they borrow from real-world cultures, they serve as an inspiration for further research and learning. Some games, yes, are didactic in nature. Breath of the Wild is not, at least not primarily. It is centered on adventure, exploration, and action, and it might be expecting too much of the designers that their game should also be a scholarly examination of Arabic culture and gender roles. Strong women may just be enough, and hopefully Gerudo Town serves as a heuristic for many gamers.

“People don't always accept parts of their culture, but question it and try to subvert it. The game avoided portraying that conflict—between the old and new forms of culture. I wanted to take part in breaking taboos, to have in-depth dialogue with the people who are subverting tradition and to feel like my actions, completing quests and talking to NPCs, actually affected and transformed the town in any way. . . . But our culture needs to be represented with depth and care, because our lives are as real as any other peoples'. Breath of the Wild doesn't deliver in this respect. We should expect more from games that borrow from real cultures: Games should tackle issues and topics like gender, race, sexuality, and politics, thanks to their ability to embody the player in a world or role. Games have the power to give players a chance, however small and ephemeral, to experience someone else's life.”

Almahr, Hussain. “'Breath of the Wild' Missed an Opportunity To Represent Arabic Culture.” Vice, 19 June 2017, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/gypn74/breath-of-the-wild-missed-an-opportunity-to-represent-arabic-culture.

[9] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, page 133.

“The Gerudo culture developed separately from the rest of Hyrule and is unique for that reason.” Ibid., 315.

[10] “According to Gerudo records there has not been another male Gerudo leader since the king who became the Calamity.”

White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, page 401.

“Even though our laws say that lone male Gerudo must become King of the Gerudo, I'll never bow to such an evil man!" — Nabooru (Ocarina of Time)

"Once every 100 years, a special child is born unto my people. That child is destined to be the mighty guardian of the Gerudo and the desert. But this child, its heart grew twisted with every passing year. The child became a man who hungered for power at any price." — Gerudo (Four Swords Adventures)

[11] While most of the Gerudo, like most people in any society, show self-interest within normal confines (i.e. not wanting solely to benefit at the expense of others), there are yet some who take this economic system too far, and almost to the point of ridiculousness. One of the Gerudo, Calyban (her name itself is interesting and rings with history), tells Link: “. . . I need something from you in return. Altruism is for suckers.” This is clearly the extreme of Gerudo philosophy, which, while competitive and tit-for-tat, is still bounded by fair trade and honorable dealing in both battle and business.

[12] “Since ancient times the Gerudo have held onto a belief that if young Gerudo women interact with men it will bring disaster. That is why entrance to Gerudo Town is forbidden to men. When a Gerudo reaches the age of marriage, she sets out from the town in search of a mate. One can encounter Gerudo all over Hyrule who are traveling on their courtship journey. Most of the Gerudo running the shops within Gerudo Town are married and have returned in order to make money.”

White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, page 139.

[13] The Gerudo are intensely skeptical of those outside their walls, and their disdain for foreigners ranges from cutely ignorant to categorically offensive. A few quotes:

“I thought that Hylians were a small, weak little people, but you’re not so bad . . .” — Ploka

“If I’m being honest, I’d prefer to ban all but Gerudo from the palace for the moment.” — Ramella

“If you want to buy fireproof elixirs, a little Goron brat is selling them. I suggest you buy one and use it.” — Ramella

“To think that the Gerudo would be able to learn something of combat from a Hylian . . .” — Teake

[14] To this end they have built a school. Concerning the relational aspect of Gerudo life, the game-makers have this to say: “However, I didn’t think that this alone was enough to represent the Gerudo, so I designed facilities and interiors based on bridal training in Japan, which includes relationship and cooking classes. This expresses how these women think about the opposite sex in a somewhat naive manner, since they have had minimal contact up until now.”

White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, page 316.

[15]“The Arbiter’s Grounds is little more than a collection of stone pillars in the northwest of Gerudo Desert. The design of the pillars is different from all the other ruins of Hyrule, which indicates that it is uniquely Gerudo. The ruins are currently buried in the sand, and little is known of them.”

White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, page 329.

[16] Muava, Breath of the Wild; also, “Meanwhile, the goddess Hylia, worshipped throughout the rest of Hyrule, is lesser known. Gerudo Town’s goddess statue can be found, forgotten, in a back alley.”

White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, page 139.

[17] "It's believed that people once came from around the world in search of the heroines' blessing." — Rotana, Breath of the Wild

[18] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, page 139.

[19] "I'm not sure if this is related, but it's said the heroines held powers that were part of a bigger whole." — Rotana, Breath of the Wild

[20] “I also included design elements from Buddhist statues that haven’t been present in the series until now, so they are influenced by both Indian and Chinese culture as a result, making their appearance in this game unique.”

White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, page 137.

[21] Though monumental Buddhist imagery can be found throughout Southern and Southeastern Asia, the Bamiyan Buddhas are too poignant a reminder to pass up, and too like their fictional counterparts to ignore. Of course, one could also draw connections between the Avukana Buddha in Sri Lanka or the Leshan Giant Buddha along the Min River in Sichuan, China.

[22] Nordland, Rod. “2 Giant Buddhas Survived 1,500 Years. Fragments, Graffiti and a Hologram Remain.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 18 June 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/06/18/world/asia/afghanistan-bamiyan-buddhas.html.

[23] "Sav'saaba. Are you a traveler? Sitting here is the chief's favorite sand seal, Patricia. But she's no ordinary sand seal . . . She’s actually something of an oracle! If you offer fruit to Patricia by placing it before her, you’ll receive some words of wisdom in return!" — Padda, Breath of the Wild

[24] Karakara in Japanese means parched or dried up, reflecting the rattling sounds of things bone dry. [See: https://tangorin.com/words/%E3%81%8B%E3%82%89%E3%81%8B%E3%82%89]

[25] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, page 315.

[26] Ibid., 316.

[27] Morris, Roderick Conway. “Early Slices of Paradise: Gardens in Ancient Times.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 13 July 2007, www.nytimes.com/2007/07/12/arts/12iht-conway.1.6629841.html.

[28] Klein, Christopher. “Hanging Gardens Existed, but not in Babylon.” History, 14 May, 2013, [Updated 1 September, 2018], https://www.history.com/news/hanging-gardens-existed-but-not-in-babylon

Note: As introduced in the article, Dr. Stephanie Dalley, a scholar of ancient Mesopotamian languages at Oxford, puts forward the intriguing (and largely convincing) theory that the site of the Hanging Gardens was at Nineveh, and that they were constructed at the behest of Sennacherib, an Assyrian king, a full century earlier than previously imagined.

[29] Morris, Roderick Conway. “Early Slices of Paradise: Gardens in Ancient Times.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 13 July 2007, www.nytimes.com/2007/07/12/arts/12iht-conway.1.6629841.html.

[30] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, pages 316.

[1] Cox, Susan. “The New Zelda Video Game Is Improved, but Can't Escape the Industry's Princess Problem.” Feminist Current, 19 Apr. 2017, www.feministcurrent.com/2017/04/18/new-zelda-video-game-improved-cant-escape-industrys-princess-problem/.

[2] Khosravi, Ryan. “'Zelda,' 'Overwatch' and the Failure to Represent Middle Eastern and South Asian Identities in Games.” Mic, 28 June 2017, www.mic.com/articles/179466/zelda-overwatch-middle-eastern-and-south-asian-identities-in-games.

[3] Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Edward Said.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 21 Sept. 2019, www.britannica.com/biography/Edward-Said#ref661781.

[4] Tropes are, by their nature, common reiterations found in media. Yet this does not mean that they are necessarily bad, or even necessarily stale. It does not seem obvious to me that the choice of a scimitar for the Sword of the Seven (Urbosa’s famous blade) is either tiresome or insensitive. Something tells me that a katana would have seemed out of place in Urbosa’s hand, and that a capybara would have made a rather ridiculous Divine Beast; these are not good solely because they fly in the face of what is expected. Within Orientalism, there is a spectrum of representation, from the realistic to the imagined, and we cannot say that because something is an orientalist trope, it is therefore an evil.

[5] Alexandra, Heather. “Despite Nintendo's Stumbles, Breath of the Wild's Fans Have Embraced Crossdressing Link.” Kotaku, Kotaku, 23 Jan. 2018, https://kotaku.com/despite-nintendos-stumbles-breath-of-the-wilds-fans-ha-1793269690.

[6] Unkle, Jennifer. “How Breath of the Wild Failed Us When It Comes To Trans Identity.” Pastemagazine.com, 9 Mar. 2017, https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2017/03/how-breath-of-the-wild-failed-us-when-it-comes-to.html.