Ikana Kingdom and the Eastern Desert

“Ikana Kingdom was founded on this land, stained with a history of darkness, drenched in blood . . . Even now it is a place where troubled, regretful spirits gather.”

— Mystery Man

To the Western mind, the East has long been a subject of fascination. For much of recorded history, the very mention of the direction brought forth conceptions of mystery, vastness, and deep spirituality. And while much could be said on this topic, especially by those of us in Western countries, for it is a large one, let it suffice to say that Majora’s Mask also builds upon this trope of the obscure-yet-enticing East. Eastern Termina is home to mountainous canyons, ancient battlegrounds, and guarded histories; it is also home to many creatures only seen within its dusty valleys and ravines, and nowhere else, nor in any other time. Unlike the three other regions of Termina, there are no bustling settlements or amenities for tourists, nor is there the anticipation of festivity and happiness — it is a place that exists in stagnation and ruin, a place whose true time was as long ago as a childhood dream.

Running eastward from Clock Town is a dusty road, given boundaries only by eight stout pillars. These pillars, as well as the gate leading east, all bear what is perhaps the chief motif of Ikana: death masks, either skeletal or merely twisted. The Eastern Gate from Clock Town is bound by two dark stones, acting as thick buttresses for the central opening, which is a highly-abstracted skull in pale grey, white, red, and black. Limned with crimson forms — which might be alphabetic or simply impressionistic — the entire gateway is marked by an air of worry: that we should look on it frantically, as garish as it is violent, and seek to be rid of it. Turning quickly away, the road to the east gives no more relief, as each squat pillar also bears a skeletal mask — two in fact, facing in opposite directions, diagonal one another — which reinforces much of what we are to see in Ikana: the overt and repetitive motif of death, mostly embodied in totems of earthly demise. Already, we know what kind of region awaits us in Ikana, and we can surmise that anyone we find there is likely far different from the other more life-affirming races we have yet come across.

— Mystery Man

To the Western mind, the East has long been a subject of fascination. For much of recorded history, the very mention of the direction brought forth conceptions of mystery, vastness, and deep spirituality. And while much could be said on this topic, especially by those of us in Western countries, for it is a large one, let it suffice to say that Majora’s Mask also builds upon this trope of the obscure-yet-enticing East. Eastern Termina is home to mountainous canyons, ancient battlegrounds, and guarded histories; it is also home to many creatures only seen within its dusty valleys and ravines, and nowhere else, nor in any other time. Unlike the three other regions of Termina, there are no bustling settlements or amenities for tourists, nor is there the anticipation of festivity and happiness — it is a place that exists in stagnation and ruin, a place whose true time was as long ago as a childhood dream.

Running eastward from Clock Town is a dusty road, given boundaries only by eight stout pillars. These pillars, as well as the gate leading east, all bear what is perhaps the chief motif of Ikana: death masks, either skeletal or merely twisted. The Eastern Gate from Clock Town is bound by two dark stones, acting as thick buttresses for the central opening, which is a highly-abstracted skull in pale grey, white, red, and black. Limned with crimson forms — which might be alphabetic or simply impressionistic — the entire gateway is marked by an air of worry: that we should look on it frantically, as garish as it is violent, and seek to be rid of it. Turning quickly away, the road to the east gives no more relief, as each squat pillar also bears a skeletal mask — two in fact, facing in opposite directions, diagonal one another — which reinforces much of what we are to see in Ikana: the overt and repetitive motif of death, mostly embodied in totems of earthly demise. Already, we know what kind of region awaits us in Ikana, and we can surmise that anyone we find there is likely far different from the other more life-affirming races we have yet come across.

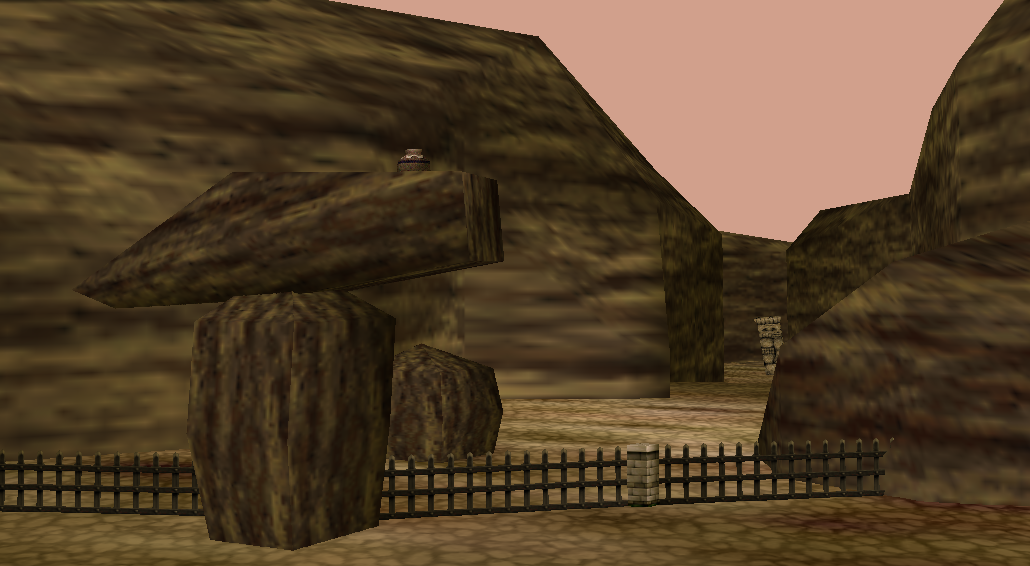

The Road to Ikana Canyon, looking westward toward Clock Town

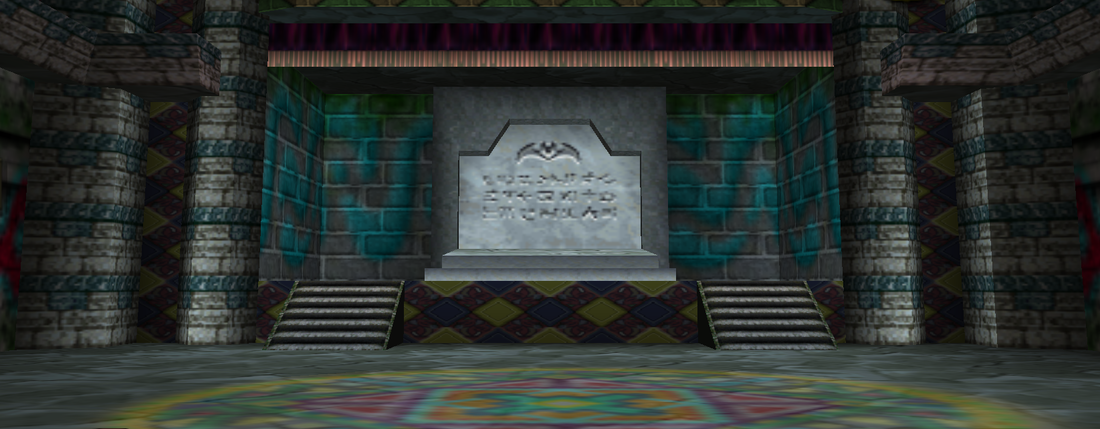

The Road to Ikana Canyon leads through an ever-deepening gully, dotted with fallen rocks, toppled pillars, and metal fences topped with blue flames. In a larger opening in the ravine, the path splits into two trails, one leading north, and the other farther east. The north road is an upward journey, with dwindling canyon walls and tightening passages, to the Ikana Graveyard, a large field open to the sky and surrounded by a forest of ancient pines. It is separated from this forest only by an old wooden fence, and here the rust-red walls of the canyon are covered with dry mosses and grass. The tombstones here, belonging to the family members of the King of Ikana Castle, also take the form of skeletons, though one grave marker towers above the rest and is engraved with strange linguistic runes. [1] We know these markings to be language-based, due to their being the same as those upon the sign near Dampé’s house farther to the north — signs that we are able to read. A winding pathway leads to a smaller field beyond, where the trail terminates at a low building. This building is where the grave-keeper lives, and it is a simple structure with one door, no windows, and a large gate under which lies a giant, resting skeleton. Two scythes and a lantern are posted above the doorway, and rose, white, and periwinkle paint are upon the outer walls. The painted designs are linear, and what appears to be a large eye, open only slightly more than halfway, stares downward, almost in curious judgment. Upon awakening the giant nearby, Link learns that this being, Skull Keeta, captain of the Ikanan Army, is held in the world of the living by regret and shame. Having ignominiously lost in battle, his soul clings to the world, even while it longs for release. When Link is able to best him in sport, he gives up his soul to Link, so that Link will be able to convey a message to his still-loyal troops upon the lower hillside. With this message, of a war that ended long ago, Link is able to give the soldiers their worldly leave, and also access secret places within the Graveyard.

While Dampé maintains watch over the graveyard by day, Captain Keeta’s soldiers do so by night. During the daytime, the graveyard merely appears haunting, but at night, it becomes haunted, as the undead soldiers of Ikana awaken to patrol among the tombstones. Beneath the graveyard is a series of caverns, mostly empty but for a few embellishments in some of the more well-defined chambers. Door enclosures here are decorated with a flying bat motif, done in red against gold, with offset emerald gems. The final room in this complex is almost an auditorium; whimsical colors stand in opposition to the location and gloom of the dungeon, and the colorful mixes of yellow, purple, teal, and red give an almost carnival-esque feel to the room, which is dominated at its front by a stage — elevated and blocked off by a red curtain. Upon defeating the guardian of this room, the curtain is raised to reveal a tombstone, one which belongs to an important personage in Ikana, who will quite soon have a critical role to play in its healing.

Departing from the graveyard and once again traveling east, Link meets two strange figures. One is a soldier named Shiro, who has been trapped in this region for many years, and the other is the Mystery Man, an enigmatic being who seems to find comfort with the undead. [2] This strange individual helps Link scale a tall rock face which leads to Ikana Butte, an open tract of dry land that stretches into a large, slow-moving river at the foot of a great cliff. This area is the true beginning of the land called Ikana Canyon, and atop the steep precipice near the river is found the isolated settlement of this land. Immediately noticeable here is a vague feeling of unease: everything is clearly dead — the soil, plants, and even the air — but the land seems restless, as if something has caused it to become animated and watchful.

Departing from the graveyard and once again traveling east, Link meets two strange figures. One is a soldier named Shiro, who has been trapped in this region for many years, and the other is the Mystery Man, an enigmatic being who seems to find comfort with the undead. [2] This strange individual helps Link scale a tall rock face which leads to Ikana Butte, an open tract of dry land that stretches into a large, slow-moving river at the foot of a great cliff. This area is the true beginning of the land called Ikana Canyon, and atop the steep precipice near the river is found the isolated settlement of this land. Immediately noticeable here is a vague feeling of unease: everything is clearly dead — the soil, plants, and even the air — but the land seems restless, as if something has caused it to become animated and watchful.

Ignoring the monolithic structure to the south for the present, many other, smaller structures can also be found here, clinging to the terraced walls of the canyon like so many fallen boulders. Squat and sand-colored, these erstwhile houses or shops all tightly embrace the cliff walls, having few, round windows and oddly-angled walls. Asymmetrical, these structures seem like ancient vases that have been strained with age and are now bowing out toward the middle in an effort to come to rest. With their wooden roofs, almost resembling straw hats, and the circular windows edged with blue tile and separated into four panes by means of rough wooden mullions, these homes all but appear to be worn-out faces — faces which saw far more than was bearable, and which long ago ceased trying to keep up appearances. Fading paint of rose, tan, and grey-brown, and cracks in the outer walls all expose the age of these structures, which speak of a period of long disuse.

Above left: two colorful and ornate Romani Vardo from Kent, England — By: Jodi — Own Work, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/squirmelia/830769285; Above right: The Music Box House of Ikana

Much stranger than any of these houses, however, is the Music Box House, which dominates the first level of terracing and holds a key spot in the valley next to the Ikana River. From the outside, with its memorable gambrel roof and imaginative, colorful flourishes of design, the overall structure seems the happy union between an old stone barn and a Romani vardo, or caravan wagon. [3] Of course, this is an imaginative conceptualization, but then again, this is an imaginative building. Old blocks of stone, greenish-grey in color, are stacked fancifully by the bed of the river, which would have once flowed underneath a large waterwheel, done in wood and steel. Small, deep, multifunctional windows let both light and air inside, maintaining equilibrium of temperature and the quality of the air, while at the same time keeping out anything harmful or unwanted. This structure may as yet seem unremarkable, but the roof, composed of long boards and painted with almost childlike green, gold, and red, and in simple geometric figures and wispy curls, makes it anything but ordinary. Already, we see a delightful blend of necessary, well-conceived defense, and spirited, youthful whimsy. The crowning jewel, though, is the large apparatus affixed to the roof. Three large phonographic horns — one small, one medium, and one large — protrude absurdly from the rooftop, and, for now, in their silence, seem without value.

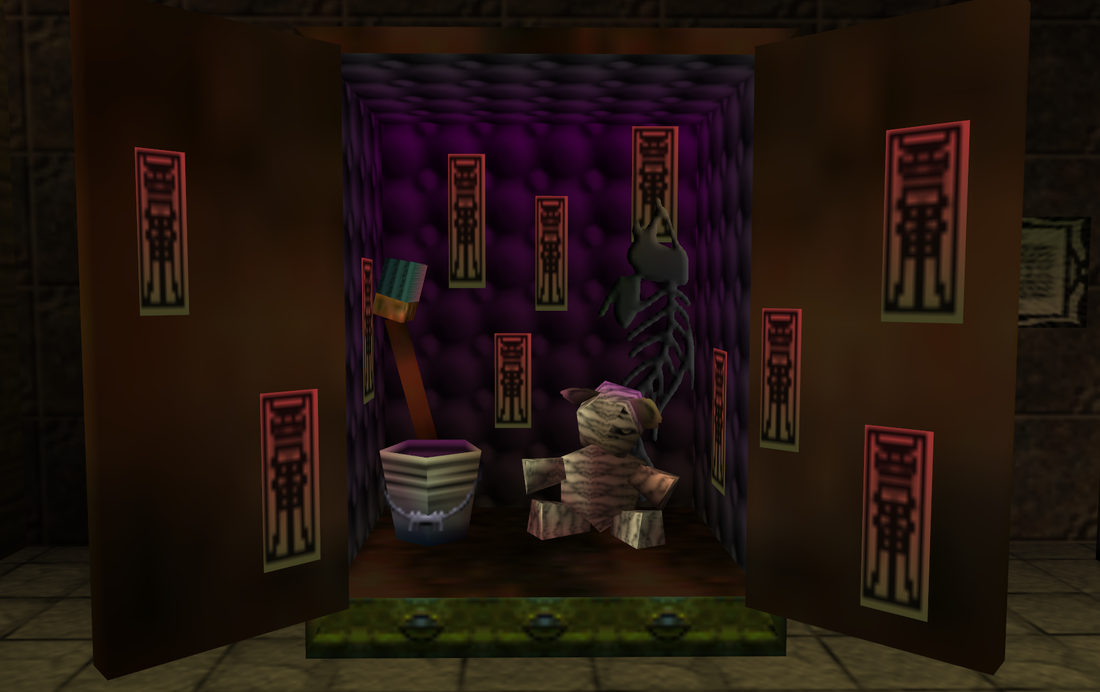

The inside of the house is well-lit and cozy — the very image of Home, and an oasis in the dreary landscape of Ikana. It merely existing here is a stark paradox, made beautiful simply due to contrast. Warm bricks and polished woods provide the backdrop for more fanciful paintings, potted plants add life, and the worn, yet ornate, rugs, and table set for two all show that this place is indeed a home. Other small touches, like a cluttered mantelpiece with plates and other ceramics, and the white linens and centerpiece upon the table complete an already-charming picture. The ceiling above is painted in ruby and turquoise and mirrors the exterior of the roof outside. A carved bannister demarcates the staircase from this main room, and is the last thing touched by Home within this structure. The downstairs chamber is a gloomy laboratory and study, filled with mechanical necessities and other equipment. Dark and dingy, with massive amps, gears, and boilers, wrenches and other tools lying scattered upon the floor, the room is dominated by an object leaning against the far wall. Amidst finely-labeled diagrams, maps, and books is a casket, in which rest a bucket and mop, a fish skeleton, a stuffed doll, and something else entirely, once held in by what appear to be Japanese ofuda, or spirit talismans.

This thing that lunges so piteously at Link is Pamela’s father, a being who is, “waiting for its human heart to be healed.” [4] Although his name is never given, Pamela’s father is a famed academic who researches supernatural phenomena, ranging from fairies to ghosts and the undead. And his research has borne much fruit by the time Link arrives; not only has he uncovered the secret to pacifying the hungry and stalking Gibdos through music (a song which is called Farewell to Gibdos), he has partially revealed the disparate histories of Ikana Canyon — histories of the Garo and their relation to the Ikanan War — and has himself mounted an exploration into the bottom of the well. And while Pamela worries about their safety and livelihood in this place, her father, dedicated academic that he is, likely considers safety a secondary concern to discovery, knowledge, and the pursuit of truth. However, his excursion to the well-bottom yielded nothing but a curse which led him to become partially Gibdo. And as a second tragedy, the nearby river dried up at its source, stopping the water wheel, and therefore the music that kept them safe. Powerless to help her father, and, at the same time, wanting to protect him, Pamela trapped her father in a casket in the basement, and locked their door to the dangers outside, effectively sealing them both off from the world.

This thing that lunges so piteously at Link is Pamela’s father, a being who is, “waiting for its human heart to be healed.” [4] Although his name is never given, Pamela’s father is a famed academic who researches supernatural phenomena, ranging from fairies to ghosts and the undead. And his research has borne much fruit by the time Link arrives; not only has he uncovered the secret to pacifying the hungry and stalking Gibdos through music (a song which is called Farewell to Gibdos), he has partially revealed the disparate histories of Ikana Canyon — histories of the Garo and their relation to the Ikanan War — and has himself mounted an exploration into the bottom of the well. And while Pamela worries about their safety and livelihood in this place, her father, dedicated academic that he is, likely considers safety a secondary concern to discovery, knowledge, and the pursuit of truth. However, his excursion to the well-bottom yielded nothing but a curse which led him to become partially Gibdo. And as a second tragedy, the nearby river dried up at its source, stopping the water wheel, and therefore the music that kept them safe. Powerless to help her father, and, at the same time, wanting to protect him, Pamela trapped her father in a casket in the basement, and locked their door to the dangers outside, effectively sealing them both off from the world.

Flat's headstone beneath Ikana Graveyard — notice the recurring bat motif atop the marker

A pair of estranged brothers also lingers in this region, separated by envy, anger, and by regret. Flat and Sharp, known as the Composer Brothers, fought in life, and when Sharp entered into a pact with the devil and sealed his brother beneath the graveyard, an anguish once solely between brothers soon became an anguish to the entire valley of Ikana. Spurred on by the masked one, and with a composition called the Melody of Darkness, Sharp holds sway over the source of water within this region, and only when Link is able to liberate Flat’s spirit from beneath the graveyard is he given a melody that can cleanse Sharp’s soul. The Song of Storms is emblematic of the tears and anger shed and felt by Flat during his long imprisonment, and it is this song that heals his brother’s soul, returning the river to normalcy and sending them both peacefully into the hereafter.

After the river again begins to flow in its course through the valley, a cheerful song fills the deadened air, driving off death and danger, causing Pamela to risk stepping outside to see what had happened. Link slips into the Music Box House unnoticed, and uncovers Pamela’s father in the basement, restoring him to his true form with the Song of Healing. Though still protective of her father, Pamela thanks Link, even while she tells her father nothing of his curse or of his healing. In this way, Pamela has almost become the adult, while her father, ever obsessed with his playthings, seems more a child. While her father was changed, she became his guardian and protector, and even after he is returned to normal, still she keeps protecting him – poignantly, this time, from knowledge, which is life and essence to a researcher, as music is life to the composer, or language to the poet.

After the river again begins to flow in its course through the valley, a cheerful song fills the deadened air, driving off death and danger, causing Pamela to risk stepping outside to see what had happened. Link slips into the Music Box House unnoticed, and uncovers Pamela’s father in the basement, restoring him to his true form with the Song of Healing. Though still protective of her father, Pamela thanks Link, even while she tells her father nothing of his curse or of his healing. In this way, Pamela has almost become the adult, while her father, ever obsessed with his playthings, seems more a child. While her father was changed, she became his guardian and protector, and even after he is returned to normal, still she keeps protecting him – poignantly, this time, from knowledge, which is life and essence to a researcher, as music is life to the composer, or language to the poet.

Above, left to right: A Gibdo guarding a doorway beneath the well, and the final chamber of the well, which houses the Mirror Shield

Now equipped with the Gibdo Mask, taken from Pamela’s father, Link must traverse the maze at the bottom of the well. The entrance to the well is located upon the utmost level of the canyon, though it lies deep beneath the ground. The maze at the bottom is sizable, and, given the treasure it houses, is well-defended. Eerily, each doorway in this dungeon is guarded by a speaking Gibdo, every one of which has a different desire to ask of Link. In the dim light of the maze, he barters with the dead, who ask for trinkets and baubles before allowing him to pass, eventually claiming the Mirror Shield which rests in a grey-stone room lit by the sun. With this shield, Link is finally able to enter into the Ancient Castle of Ikana, once home to the vast and powerful Ikana Royal Family.

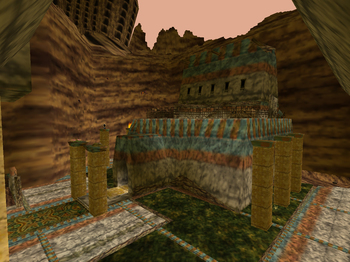

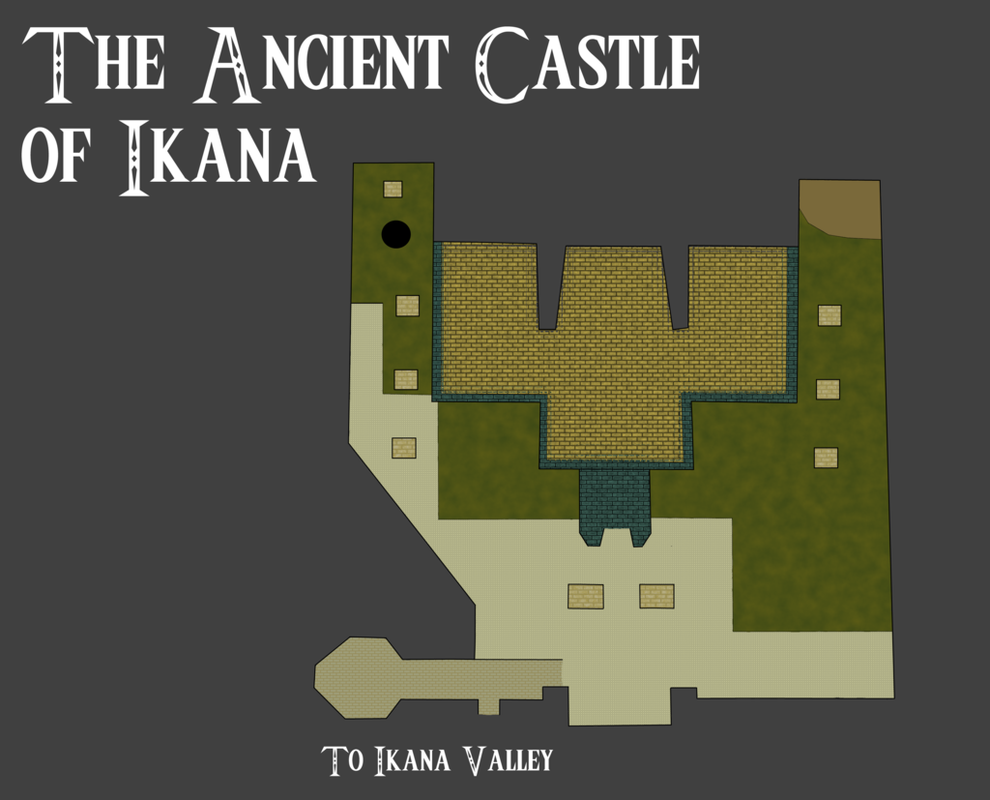

Ikana Castle is a commanding structure which sits on the edge of the precipice leading downward into Ikana Canyon. The main fortification of the castle faces north, while the other three directions are protected by both cliff and mountain. Erected on a strong site, these natural barriers formed perfect boundaries for the stronghold and greatly lessened the production costs of those who built it. And while no castle is impenetrable, they are all built to be so. To this end, the front gate has been sealed so as to be impassable, though to the side of the main gate is a smaller entrance — perhaps a postern gate — which leads to the inner courtyard, an area which is also accessible by way of the ancient well. The strong outer wall was created out of heavy brown-colored stone, likely quarried within Ikana, due to its similarity with the canyon walls; its overhanging battlements, upon which troops may have patrolled, would have made scaling the barricade exceedingly difficult. There are no crenellations upon the wall, and its lack of other defensive architectural details makes it incredibly simplistic as a protective measure. The dusty walls are painted in a pattern resembling the dentil blocks (the tooth-like design that looks similar to crenellations atop a fortification) of classical architecture, with interlocking red and teal parts. Wooden posts project from the battlements, and may have once held flags or pennants. The gate is composed of two heavy doors of a tan material, likely a metal, and depicts two red birds of ostentatious plumage. They are not realistic, and may be emblematic — perhaps a sigil of the Royal Family of Ikana. These two birds face one another, with their red-gold bodies and green-on-gold patterned wings, while the area around the gate is supported by four load-bearing pillars. Interestingly, the top of the gate does not reach the lintel above it, but instead gives way to an open space through which the interior courtyard and keep can be seen.

Two views of Ikana Castle's inner keep. In the background, the steep mountainsides are shown, as well as the looming Stone Tower

Inside the courtyard, protectively enclosed behind tall walls and even taller mountains, is the donjon, or main keep of the castle. This structure is built into the natural juxtaposition of two high cliffs. With this location, it is likely that the only assault could have been a frontal one (from the north), and so the keep faces its defenses in that direction. [5] Ten monumental sandstone pillars composed of large blocks and surmounted by simple capitals in green and red paint surround the donjon, and are carven images of a vertebral column, once again adding complexity to the overall theme of the region. A few of these pillars are capped in fire, and what purpose they once served is unknown. Yet, the courtyard is not solely meant to be a defensive bulwark; as with many more modern castles (post-Medieval structures), this one also indulges in charming gardens and footpaths. The courtyard is actually composed of a system of alternating textures. Squares of grass and stone checker the ground, adjoining a tiled pathway, and small water-channels crisscross the enclosure and would have provided nourishment to the gardens. The paint upon the walls echoes that of the exterior, although the foundational stonework of the interior is far more ornate. The pathway leading from the main gate into the keep is highly decorated in many colors, and introduces us to many designs to be found inside the keep. Looking at the main structure, with its triangular-arch entrance and sloping walls (once again reminiscent of a step pyramid, or ziggurat), we immediately lose the ostentation of the garden within these defensive fortifications. Consisting of two primary levels, the only noteworthy aspects of the keep are the diminutive loopholes, or arrow slits, along the walls, and the iron fence atop the parapets, which would have protected Ikanan soldiers from ascending enemies trying for hand-to-hand combat while at the same time providing a slight cover out of which to shoot. This latticework consists of two differently-sized squares, which may have been purposeful; while the smaller square opening would have easily permitted an arrow to pass through, the larger ones would have allowed for larger objects — like stones or other projectiles — to be dropped upon the enemy. The second level is also guarded from above by five arrow slits that have an uninterrupted view of the upper battlements. In all, while the castle architecture displayed here is simplistic compared to many real-world examples, we know that this structure was designed to withstand a siege, and to protect the Royal Family and all its holdings.

The layout of Ikana Castle is in three parts: an eastern passage, a western passage, and the central hall, through which the throne room is accessed. True to all dungeons, there is no immediate access to the central chamber, and Link must pass through the two flanking passages before entering the great hall. The first hall, which is open to the air through the main doorway, has no visible ceiling, as its four vertebral pillars stretch into nothing in their cream and gold designs. The walls echo the teal and rust paint of the outside, and an enormous emblem of the sun on the floor connects this place to the Mirror Shield and the power of light over gloom. There are four major motifs at work within the castle, and the first theme is to be found upon the round doors: as upon the tiled pathway leading to the inner keep, this door is done in myriad colors, and depicts a strange creature with large eyes and bowed legs. Whatever this being is, it is winged, squatting down, as if preparing to launch into flight; its legs and arms are proportionally very thin when compared to its enormous belly, and its arms are raised on either side of its sallow face. Two green eyes look out from this mask, above a red mouth or nose, and these eyes appear to be wounded, as if a knife caused scarring above them and below. The bright colors seem to encourage playfulness, but here they achieve anything but a sense of the enjoyable. The western passage is momentarily blocked off, and the eastern passage must be taken initially. Checkered floors in teal and orange rest under a falling ceiling, and diamond-patterned gratings (like those outside, but angled slightly) cover the walls, which are each engraved with different motifs. The second motif to be found here is that of the twin birds, as last seen upon the main gateway into Ikana Castle. Not only are they done in metalwork upon the lattices, but they are carved into the walls. This is one of three distinct friezes, or engravings, to be found in the castle. These birds, green on grey, are line drawings, lacking complexity of form, and are repeated in blocks far up on many walls. Another motif holds this same position, and is of a cartoonish skull, with large, yellow eyes, and a disproportioned cranium and small jaw.

The second room in the eastern passage has fallen into nothingness, and where once was a bridge, or floor, now there is only a black pit. This room has been turned into an obstacle, and is protected by hanging spiked balls and in-the-way pillars. This chamber carries the bird frieze outlined above. Beyond this room, and echoed on the western side, are two small chambers that lead to the second floor. Steps reach upward, and a floor of simple wood and green bricks twists into a spiral staircase dominated by our last key motif. This motif is perhaps the strangest and most unnerving icon — a recurring panel depicting a skeletal figure, bowed in prayer. Resting upon the head of a horned animal, each skeleton is kneeling, legs bent in prostration, hands folded in front of its chest, with eyes and mouth open, as if waiting for divine grace. Something golden appears to be hanging from its hands, like a religious implement — a rosary, or length of prayer beads — used in an instance of supplication. These skeletal beings face in the direction of the rising stair, meaning that Link travels with them, in a way, up to the second story of the castle. Concerning the outer level, there is not much to say. This area does allow Link to access the western hall, however, opening a hole in the ceiling and allowing light to pierce the blackness. With the aid of the sun, Link finds himself in the secondary western room, which may show us what its twin room on the other side of the fortress was once like. Ultimately, clearing these two halls opens up a path to the throne room, enclosed by high pillars and great walls. The throne room itself is a microcosm of all design in Ikana Canyon, displaying each motif discussed thus far, while creatively adapting each design to reflect the purpose of this chamber. The large bird seen upon the outer gate is once again found here, though in this incarnation it is standing upon a skull, bowing. Four bird-patterned screens flank the throne in deep red, and everything points to this raised dais at the far end of the hall. The throne itself is large, and of grey stone. But far more interesting than the throne is the being that sits upon it.

The second room in the eastern passage has fallen into nothingness, and where once was a bridge, or floor, now there is only a black pit. This room has been turned into an obstacle, and is protected by hanging spiked balls and in-the-way pillars. This chamber carries the bird frieze outlined above. Beyond this room, and echoed on the western side, are two small chambers that lead to the second floor. Steps reach upward, and a floor of simple wood and green bricks twists into a spiral staircase dominated by our last key motif. This motif is perhaps the strangest and most unnerving icon — a recurring panel depicting a skeletal figure, bowed in prayer. Resting upon the head of a horned animal, each skeleton is kneeling, legs bent in prostration, hands folded in front of its chest, with eyes and mouth open, as if waiting for divine grace. Something golden appears to be hanging from its hands, like a religious implement — a rosary, or length of prayer beads — used in an instance of supplication. These skeletal beings face in the direction of the rising stair, meaning that Link travels with them, in a way, up to the second story of the castle. Concerning the outer level, there is not much to say. This area does allow Link to access the western hall, however, opening a hole in the ceiling and allowing light to pierce the blackness. With the aid of the sun, Link finds himself in the secondary western room, which may show us what its twin room on the other side of the fortress was once like. Ultimately, clearing these two halls opens up a path to the throne room, enclosed by high pillars and great walls. The throne room itself is a microcosm of all design in Ikana Canyon, displaying each motif discussed thus far, while creatively adapting each design to reflect the purpose of this chamber. The large bird seen upon the outer gate is once again found here, though in this incarnation it is standing upon a skull, bowing. Four bird-patterned screens flank the throne in deep red, and everything points to this raised dais at the far end of the hall. The throne itself is large, and of grey stone. But far more interesting than the throne is the being that sits upon it.

Perhaps this is a good time to discuss a bit of backstory. The military history of this region is reasonably well-divulged in-game, and there is no shortage of theories concerning the various histories alluded to during this chapter of the game. An ancient battle is referred to again and again in this region, by both the living and the dead, and it was this early feud that both destroyed the kingdom and ruined the land. Simply put, it was a war between two primeval enemies: the Garo, who came from lands unknown, and the Ikanan Kingdom that had long guarded this region.

The Garo, who now lurk in the shadows of Ikana, were once adversaries of Ikana Kingdom. Acting as spies within the region, gathering intelligence and information, these soldiers were in the vanguard of what was assumedly a fearsome army. No army can win solely through espionage, after all. Led by the Garo Master, the head of their intelligence organization, the Garo were governed by a strict code of honor, not entirely dissimilar to the concept of Bushidō found within Japanese thought and military ethics. Even when they are defeated in death, they are still bound by this code, giving praise to their vanquisher, after which they promptly end their own lives, leaving nothing at their death. [6] Their rage against the Kingdom of Ikana can still be felt, even after their passing, in the wisdom they bestow unto Link: not only do they reveal ways into the Ancient Castle, but they reveal the method to quelling the mighty King’s rage and defeating him in combat. [7]

As we know, the Kingdom of Ikana was ruled over by a royal family, of which we know only one name – that of King Igos du Ikana. A poetic man, and one who is clearly thoughtful even while being belligerent, Igos du Ikana likely reigned over Ikana during the great war in which this region was ultimately destroyed. He forces Link into a trial by combat, in which Link must best the two top swordsmen of Ikana, as well as the King himself, and when he is defeated, he, like the Garo, offers Link both advice and aid. Igos, who found himself brought back from death, details this curse to Link, echoing the words of Sharp, saying: “It all happened after somebody thrust open the doors of that Stone Tower . . . To return true light to this land, you must seal the doors of the Stone Tower where the winds of darkness blow through. But Stone Tower is an impenetrable stronghold. Hundreds of soldiers from my kingdom would not even be able to topple it. It is far too reckless for one to take on such a challenge . . . And so . . . I grant to you a soldier who has no heart. One who will not falter in the darkness . . .” As if the King knows exactly what awaits Link in the Stone Tower, he teaches Link a sacred melody, the Elegy of Emptiness, which allows Link to create statues of himself and his other forms. From this dialogue, we gain a sense of historical proportion concerning this land. Long after the battle, which likely happened centuries ago given the disrepair into which the structures of this land have fallen, an interloper to the region — the masked one — threw open the doors of the Stone Tower, causing the dead to once again return to life. Called back from their rest, they began to wander and haunt the countryside, terrifying those few inhabitants still left in the region. And while some have speculated that the Doors were opened long ago, it is only recently that the undead have once again appeared. [8][9] To restore the land to its silent rest, then, the evils of the Stone Tower must be overcome, and the structure that has been looming over all of Ikana up until this point becomes absolutely inescapable.

The Garo, who now lurk in the shadows of Ikana, were once adversaries of Ikana Kingdom. Acting as spies within the region, gathering intelligence and information, these soldiers were in the vanguard of what was assumedly a fearsome army. No army can win solely through espionage, after all. Led by the Garo Master, the head of their intelligence organization, the Garo were governed by a strict code of honor, not entirely dissimilar to the concept of Bushidō found within Japanese thought and military ethics. Even when they are defeated in death, they are still bound by this code, giving praise to their vanquisher, after which they promptly end their own lives, leaving nothing at their death. [6] Their rage against the Kingdom of Ikana can still be felt, even after their passing, in the wisdom they bestow unto Link: not only do they reveal ways into the Ancient Castle, but they reveal the method to quelling the mighty King’s rage and defeating him in combat. [7]

As we know, the Kingdom of Ikana was ruled over by a royal family, of which we know only one name – that of King Igos du Ikana. A poetic man, and one who is clearly thoughtful even while being belligerent, Igos du Ikana likely reigned over Ikana during the great war in which this region was ultimately destroyed. He forces Link into a trial by combat, in which Link must best the two top swordsmen of Ikana, as well as the King himself, and when he is defeated, he, like the Garo, offers Link both advice and aid. Igos, who found himself brought back from death, details this curse to Link, echoing the words of Sharp, saying: “It all happened after somebody thrust open the doors of that Stone Tower . . . To return true light to this land, you must seal the doors of the Stone Tower where the winds of darkness blow through. But Stone Tower is an impenetrable stronghold. Hundreds of soldiers from my kingdom would not even be able to topple it. It is far too reckless for one to take on such a challenge . . . And so . . . I grant to you a soldier who has no heart. One who will not falter in the darkness . . .” As if the King knows exactly what awaits Link in the Stone Tower, he teaches Link a sacred melody, the Elegy of Emptiness, which allows Link to create statues of himself and his other forms. From this dialogue, we gain a sense of historical proportion concerning this land. Long after the battle, which likely happened centuries ago given the disrepair into which the structures of this land have fallen, an interloper to the region — the masked one — threw open the doors of the Stone Tower, causing the dead to once again return to life. Called back from their rest, they began to wander and haunt the countryside, terrifying those few inhabitants still left in the region. And while some have speculated that the Doors were opened long ago, it is only recently that the undead have once again appeared. [8][9] To restore the land to its silent rest, then, the evils of the Stone Tower must be overcome, and the structure that has been looming over all of Ikana up until this point becomes absolutely inescapable.

The existence of the Stone Tower is no secret in Termina. It is a building that dominates the horizon, like three enormous cacti, fused together, cutting a dark shadow across a flushed and rosy sky. Covered in holes within and without, the building also resembles a massive hive of insects; a feeling of being watched is not without design, as unseen eyes may be watching from the countless windows of the tower, each of which seems a blackened eye in itself. The passage in the southeast corner of Ikana Village, which takes the form of a monolithic carved humanoid, leads to the Stone Tower, and recapitulates the vaguely-humanoid design elements to be seen nearly everywhere in Ikana. This humanoid sculpture is highly-detailed, from its squatting legs and resting arms forming walls to either side of the ramp upward, to a tongue which acts as the ramp itself. Its hands rest upon its legs, providing two platforms on either side of the ascent, and the gateway is a tunnel within the creature’s mouth. The face is completely flattened, evincing two gaping nostrils, huge blank eyes with almost no white, and an agape mouth with long, sharp teeth and stretched lips. This smaller architectural figure is indicative of many themes at play within Stone Tower and its Temple, and it creates an unnerving atmosphere when combined with the massive towers that loom beyond it.

In many ways, the Stone Tower itself is more a negative space, in which the form of a tower has been removed directly from the mountain, creating a vast chasm in its place. This ascent acts as a massive security device for its temple, and is, therefore, a more utilitarian space than one holy in nature. Primarily consisting of a series of terraced platforms that ascend in uneven, often disjointed, patterns, bridges are made through the air by blocks activated by pressure switches and Link’s ability to create effigies of his many forms. These blocks, it should be said, mimic perfectly the statuesque entrance to the tower itself, and lend a sense of continuity to what is ultimately the largest architectural mask to be found anywhere in Termina. The top level of the Stone Tower is dominated by this enormous stone mask, flanked by four tall towers, resting upon intricate masonry. The towers are strangely phallic, rising, tapering, and then widening again, and are capped with what could be said to be the cap of a mushroom. The stone, as we will see throughout this temple, is dull grey, and joined together completely without mortar. Each of these towers has a series of small circular windows bound in orange, with a triangular orange pattern around each base. On one side of the mask is a branded fist, partially clenched, with its finger extended toward the welkin with a flame upon its tip. It is painted orange, green, and cream, and seems to be pointed in either defiance or ritual. We can discern that there would have been a corresponding hand on the other side of the mask (though not what the hand would have been like), as the structural foundation is the same on the opposite platform, but for an area that is clearly collapsed. The face itself is entirely grotesque. Aside from being frighteningly tattooed in shapes of olive, orange, and white, its eyes are completely hollow and filled with fire, and its gaping mouth, with drawn lips and narrow teeth, once again forms an entryway with a tongue as its ramp. Because of this, in a way, the temple resting within becomes the body of this creature — a disturbing extension of a disturbing being.

The temple itself has a very pensive, calming atmosphere. Here, of all places within Termina, do we feel closest to the open sky, and to the elements. Most chambers in this temple are actually courtyards which look upon the vast blue of heaven, and we clearly discern that this temple — its designs, layout, and atmosphere — has been built to augment and do homage to the sky. There are very few design elements present in this temple, but for two small suns, in red and yellow, upon each doorway, and a motif that runs, in some form, throughout the entirety of the temple. Consisting of four drops of fire flanking a central pillar upon which rests a circle — likely representing the sun — this image can be seen on floors, walls, upon the forehead of the interior mask, as well as in the latticework and fences, and is brought into focus and elaborated as it graces ornate mirrors, and, most clearly, the “blood-stained, red emblem outside the temple.” [11] The predominant architectural feature in this temple, however, is the plain stone mask in the initial courtyard which many have likened to an image of Majora’s Mask itself. And while it may or may not be — for it is certainly not conclusive — it is certainly a curious design very different from any of the other architectural masks that we have yet seen. As even five-minutes time spent in this place will show, Stone Tower Temple is an ancient structure with more mystery in it than in any other temple within Termina; the dusty ruins, kept clean only by the wind and open air, suggest age without depth, and its simplicity runs counter to what we feel should be an incredibly complex and detailed structure.

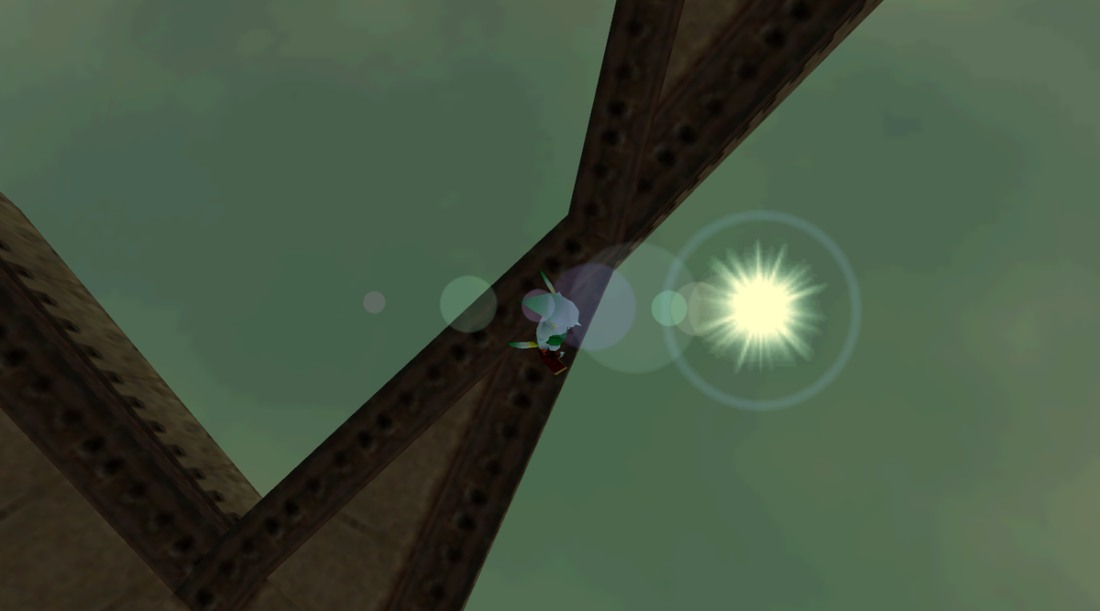

In one of the most truly wonderful and intensely confusing moments of this story, the temple is rearranged, so that “the earth is born in the heavens and the moon is born on the earth.” [12] Where once the sky was above and ground below, the center of perception — indeed, of gravity itself — has changed entirely, so that we find ourselves walking upon small pathways through the heavens, while a looming earth rests above our heads. To me, this feeling is almost indescribably beautiful, even while it is equally unsettling. Having nothing but a blue expanse beneath one’s feet at once liberates one from all preconceived notions of reality, and forces an acceptance of both change and profound absurdity. This revolution throws us into an almost religious moment, or at least one of life-altering consequence, when we are forced to realize just how tenuous our grasp on knowledge, reality, and perception actually is. Whether Termina is within a hollow earth or on the opposite side of a flat earth – or what motif represents what, or for what purpose this place was built — all these trifles become irrelevant in the face of such satori, when the soul confronts something so completely and utterly different that the world is, for a moment, born anew.

In one of the most truly wonderful and intensely confusing moments of this story, the temple is rearranged, so that “the earth is born in the heavens and the moon is born on the earth.” [12] Where once the sky was above and ground below, the center of perception — indeed, of gravity itself — has changed entirely, so that we find ourselves walking upon small pathways through the heavens, while a looming earth rests above our heads. To me, this feeling is almost indescribably beautiful, even while it is equally unsettling. Having nothing but a blue expanse beneath one’s feet at once liberates one from all preconceived notions of reality, and forces an acceptance of both change and profound absurdity. This revolution throws us into an almost religious moment, or at least one of life-altering consequence, when we are forced to realize just how tenuous our grasp on knowledge, reality, and perception actually is. Whether Termina is within a hollow earth or on the opposite side of a flat earth – or what motif represents what, or for what purpose this place was built — all these trifles become irrelevant in the face of such satori, when the soul confronts something so completely and utterly different that the world is, for a moment, born anew.

Notes and Works Cited:

[1] Majora’s Mask. Dampé the Gravekeeper. Nintendo. 26 Oct. 2000. Video Game.

[2] The brief story of the soldier, Shiro, is a strange one. Shiro, bearer of the Stone Mask, out of ignorance, curiosity, or an unnoticeable personality, has been trapped in the canyon for many years, waving his arms at passersby, waiting for rescue. True to the nature of the Stone Mask, wearing it causes one to become as plain and as overlooked as a stone. Only when Link is able to locate him with the Lens of Truth and give him a medicinal potion to cure his ailments does Shiro bequeath unto Link his precious, yet unlucky, mask, giving Link the power to walk unnoticed throughout much of Termina. While certainly a useful tool for concealment, it is undoubtedly one of the stranger masks within Termina.

[3] A vardo is actually a quite modern invention, having only been invented (and popularized) sometime around 1850 in England. These caravan wagons are almost perfectly emblematic of the wandering lifestyle, and call to mind a vast sense of freedom and a unique relationship with the land. While there are many types of vardos, made at different times and for different purposes, there are common features to which all of them are bound. They are generally intricately decorated, with carvings and bright paint, and are sometimes even gilded with gold leaf; in fact, these embellishments were quite often a symbol of wealth and culture, and commonly incorporated various images of the Romani lifestyle. For more information, please feel free to visit this site: http://gypsywaggons.co.uk/varhistory.htm

[4] Majora’s Mask. Tatl. Nintendo. 26 Oct. 2000. Video Game.

[5] While not directly referenced in this piece, these maps (http://nj242.deviantart.com/) of much of Termina have been extremely helpful during my writings. This note is simply to acknowledge the work put into creating them, and to give credit where it is due.

[6] Ritualized death is both a worldview and a law for the Garo. Regular Garo are all bound to their manner of life, saying, “To die without leaving a corpse . . . That is the way of us Garo,” while their leader, the Garo Master, changes the grammar slightly, stating, “Die I shall, leaving no corpse. That is the law of us Garo.” Although the difference may seem slight, it reveals something, a minor change that perhaps comes with rank. While normal soldiers are possibly governed by their own worldview, which relies on personal dedication and will-power, it seems as though higher-ranking Garo were bound to a law, which may have been imposed externally, as well as internally through a personal code. It may also be that the Garo simply wished to rid their captors of any evidence or information, and to prevent themselves from being taken and tortured. Regardless, these differences ultimately matter little, for both the Garo and their Master all choose to take their own lives upon being defeated, maintaining honor even after death.

Majora’s Mask. Garo Ninja and Garo Master. Nintendo. 26 Oct. 2000. Video Game.

[7] A secret entrance: “The well atop the hill and the well at Ikana Castle’s inner garden are one.” A way into the throne room: “A hole can be opened in the ceiling of a particular room in Ikana Castle. But it cannot be broken without an explosive with incredible might.” Even a way to overthrow the King of Ikana: “To counter the rage of the King of Ikana Castle, burn away that which disrupts the light and shine the sacred rays on the King.”

Ibid.

[8] As mystery inevitably calls for speculation, Ikana Canyon has no great dearth of fan-based theories. Some theories attempt to connect the spirituality of Termina to the Golden Goddesses of Hyrule (http://www.zeldadungeon.net/2011/09/ikana-hyrules-shadow/ ), some pieces address the haunting strangeness of the Elegy of Emptiness (https://withaterriblefate.com/2015/02/11/a-soldier-who-has-no-heart-understanding-the-elegy-of-emptiness/), and some put forward the hypothesis that the Garo opened up the doors to the Stone Tower in an attempt to simply destroy the entirety of the region, not just the Ikana Royal Family (http://xilfy.com/v/kzkj7OywL7I). Yet others draw biblical connections between the Stone Tower and the Tower of Babel (http://zrpg.net/forums/viewtopic.php?f=10&t=3185). In short, due to the vacuum of verifiable history within Majora’s Mask, theories have cropped up in abundance to explain gaps, shortcomings, and mysteries. Happily, it is not within the purview of this blog to present and defend theories. It is enough to enumerate them.

[9] Concerning the exact timeline here, nothing is known with certainty. All we have are quotes from the individuals who inhabit Ikana, which may or may not be fully true. Dampé states that: “Even nowadays, the ghosts come out at night!” Sakon: “You know . . . Lately, frightening ghosts have been appearing in swarms in Ikana Village across the river.” These two quotes seem to suggest that the Doors in the Stone Tower were only recently opened, likely by Skull Kid, and that the haunting of the land is not an established, long-standing phenomenon. Curiously, these warnings only cover spirits. Creatures like Gibdos have been here for years, and likely had nothing to do with the Stone Tower being opened. Pamela divulges that she and her father used to live in town, and that only recently did they move to Ikana so that her father could continue research on the undead; her father himself tells us that he discovered the song, Farewell to Gibdos, after years of research — which means that Gibdos are not uncommon to the region and predate the more-recent phantoms.

[10] These stills have been taken from:

"Exploring Termina." Exploring Termina. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2016. <https://mujulastills.tumblr.com/>.

[11] Majora’s Mask. Garo Master. Nintendo. 26 Oct. 2000. Video Game.

[12] Ibid.

[1] Majora’s Mask. Dampé the Gravekeeper. Nintendo. 26 Oct. 2000. Video Game.

[2] The brief story of the soldier, Shiro, is a strange one. Shiro, bearer of the Stone Mask, out of ignorance, curiosity, or an unnoticeable personality, has been trapped in the canyon for many years, waving his arms at passersby, waiting for rescue. True to the nature of the Stone Mask, wearing it causes one to become as plain and as overlooked as a stone. Only when Link is able to locate him with the Lens of Truth and give him a medicinal potion to cure his ailments does Shiro bequeath unto Link his precious, yet unlucky, mask, giving Link the power to walk unnoticed throughout much of Termina. While certainly a useful tool for concealment, it is undoubtedly one of the stranger masks within Termina.

[3] A vardo is actually a quite modern invention, having only been invented (and popularized) sometime around 1850 in England. These caravan wagons are almost perfectly emblematic of the wandering lifestyle, and call to mind a vast sense of freedom and a unique relationship with the land. While there are many types of vardos, made at different times and for different purposes, there are common features to which all of them are bound. They are generally intricately decorated, with carvings and bright paint, and are sometimes even gilded with gold leaf; in fact, these embellishments were quite often a symbol of wealth and culture, and commonly incorporated various images of the Romani lifestyle. For more information, please feel free to visit this site: http://gypsywaggons.co.uk/varhistory.htm

[4] Majora’s Mask. Tatl. Nintendo. 26 Oct. 2000. Video Game.

[5] While not directly referenced in this piece, these maps (http://nj242.deviantart.com/) of much of Termina have been extremely helpful during my writings. This note is simply to acknowledge the work put into creating them, and to give credit where it is due.

[6] Ritualized death is both a worldview and a law for the Garo. Regular Garo are all bound to their manner of life, saying, “To die without leaving a corpse . . . That is the way of us Garo,” while their leader, the Garo Master, changes the grammar slightly, stating, “Die I shall, leaving no corpse. That is the law of us Garo.” Although the difference may seem slight, it reveals something, a minor change that perhaps comes with rank. While normal soldiers are possibly governed by their own worldview, which relies on personal dedication and will-power, it seems as though higher-ranking Garo were bound to a law, which may have been imposed externally, as well as internally through a personal code. It may also be that the Garo simply wished to rid their captors of any evidence or information, and to prevent themselves from being taken and tortured. Regardless, these differences ultimately matter little, for both the Garo and their Master all choose to take their own lives upon being defeated, maintaining honor even after death.

Majora’s Mask. Garo Ninja and Garo Master. Nintendo. 26 Oct. 2000. Video Game.

[7] A secret entrance: “The well atop the hill and the well at Ikana Castle’s inner garden are one.” A way into the throne room: “A hole can be opened in the ceiling of a particular room in Ikana Castle. But it cannot be broken without an explosive with incredible might.” Even a way to overthrow the King of Ikana: “To counter the rage of the King of Ikana Castle, burn away that which disrupts the light and shine the sacred rays on the King.”

Ibid.

[8] As mystery inevitably calls for speculation, Ikana Canyon has no great dearth of fan-based theories. Some theories attempt to connect the spirituality of Termina to the Golden Goddesses of Hyrule (http://www.zeldadungeon.net/2011/09/ikana-hyrules-shadow/ ), some pieces address the haunting strangeness of the Elegy of Emptiness (https://withaterriblefate.com/2015/02/11/a-soldier-who-has-no-heart-understanding-the-elegy-of-emptiness/), and some put forward the hypothesis that the Garo opened up the doors to the Stone Tower in an attempt to simply destroy the entirety of the region, not just the Ikana Royal Family (http://xilfy.com/v/kzkj7OywL7I). Yet others draw biblical connections between the Stone Tower and the Tower of Babel (http://zrpg.net/forums/viewtopic.php?f=10&t=3185). In short, due to the vacuum of verifiable history within Majora’s Mask, theories have cropped up in abundance to explain gaps, shortcomings, and mysteries. Happily, it is not within the purview of this blog to present and defend theories. It is enough to enumerate them.

[9] Concerning the exact timeline here, nothing is known with certainty. All we have are quotes from the individuals who inhabit Ikana, which may or may not be fully true. Dampé states that: “Even nowadays, the ghosts come out at night!” Sakon: “You know . . . Lately, frightening ghosts have been appearing in swarms in Ikana Village across the river.” These two quotes seem to suggest that the Doors in the Stone Tower were only recently opened, likely by Skull Kid, and that the haunting of the land is not an established, long-standing phenomenon. Curiously, these warnings only cover spirits. Creatures like Gibdos have been here for years, and likely had nothing to do with the Stone Tower being opened. Pamela divulges that she and her father used to live in town, and that only recently did they move to Ikana so that her father could continue research on the undead; her father himself tells us that he discovered the song, Farewell to Gibdos, after years of research — which means that Gibdos are not uncommon to the region and predate the more-recent phantoms.

[10] These stills have been taken from:

"Exploring Termina." Exploring Termina. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2016. <https://mujulastills.tumblr.com/>.

[11] Majora’s Mask. Garo Master. Nintendo. 26 Oct. 2000. Video Game.

[12] Ibid.