Lakebed Temple and the Lands of the Zora

The Zora have built their civilization upon the lifeblood of the world. From the throne room at the height of Zora’s Domain a great river flows, cascading down sheer cliffs and through lofty tunnels. It is this river which feeds the spiritual waters of Lake Hylia, protecting the sanctity of Zoran temples and nourishing all Hyrule through wellspring and tributary.

Speaking once again to the cosmopolitanism of Twilight Princess’s rendition of Hyrule, Lake Hylia is a site of pilgrimage for those of several races. Hylian soldiers tell Link of the complaints they have received related to the inaccessibility of the spring spirit of the lake, which makes peregrination to the shrine impossible. And though certain places are normally open to the greater public, the structures private and sacrosanct to the Zora maintain their isolation. The three main Zoran gathering places — the temple, the spring, and their domain — are all rich continuations of architectural traditions first seen in Ocarina of Time; and, indeed, because these games are within the same branch of the official timeline, the germinal works of beauty found in that previous game can be said to culminate in the construction and artistry of the Zora during the time of Twilight Princess. Though the locations of the temple and settlement may not match up precisely between games (and this is inexplicable, as with so many other things), the culture of this race has flourished magnificently.

Speaking once again to the cosmopolitanism of Twilight Princess’s rendition of Hyrule, Lake Hylia is a site of pilgrimage for those of several races. Hylian soldiers tell Link of the complaints they have received related to the inaccessibility of the spring spirit of the lake, which makes peregrination to the shrine impossible. And though certain places are normally open to the greater public, the structures private and sacrosanct to the Zora maintain their isolation. The three main Zoran gathering places — the temple, the spring, and their domain — are all rich continuations of architectural traditions first seen in Ocarina of Time; and, indeed, because these games are within the same branch of the official timeline, the germinal works of beauty found in that previous game can be said to culminate in the construction and artistry of the Zora during the time of Twilight Princess. Though the locations of the temple and settlement may not match up precisely between games (and this is inexplicable, as with so many other things), the culture of this race has flourished magnificently.

|

Above, the Amphitheater of Delphi, Greece (By Hu Totya — Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=718288)

Below, the Great Amphitheater of Hylia |

Beginning with the Hylian construction within this province, and due to the proximity of Hyrule Castle and Town, it is evident that, not only is transport through this region critical, the people find it beautiful. Viewed from the lake itself, an expansive, partially-destroyed bridge parts the sky, connecting two of the larger land masses of Hyrule. Clearly, this bridge took prodigious skill and resources to create, so far flung it is from the simpler wooden bridges that connect various parts of Hyrule Field to one another. This bridge is immense in scope, very wide, and much artistry has gone into its decoration — particularly upon its entrances and on its two low walls. The foundations may have crumbled into the water beneath, yet still it stands as a testament to the construction skills of Hylian engineers. Nearby, perched upon the cliff side, there is a certain archetypal throwback to early Western architecture. Following a small road near Hyrule Castle Town, a rise and dip in the faint path eventually reveal a large amphitheater which provides a breath-taking vista of Lake Hylia and its environs. And this was clearly taken from certain Greek hillsides: a semicircular structure facing a stage, upon which have fallen once-standing fluted, Doric columns. From this lofty stage, nearly the whole of the lake can be seen. The bridge is shown connecting to its terminal point, which burrows through a large tree on its route away from the castle. The scenic view serving as the backdrop to this stage would provide iconic and inimitable settings to performances, as well as demonstrate beauty in itself.

|

Lake Hylia seems to be a sunken lake, far deeper than it had previously been, as all land surrounding it is significantly higher, most notably present in the immense cliffs encircling the lake. The layout of Lake Hylia is very strange when compared to its counterpart in Ocarina of Time; the temple, the island, and the great tree are all present, but the proportioning is ludicrous. While these alterations have proved bewildering to those who give attention to maps and history, it should be remembered that this series works with concepts and changes, instead of focusing on making its own inherent timeline cohesive or understandable.

The spring of the Light Spirit Lanayru draws its influence from things seen within the previous Water Temple — primarily, the serpentine nāgás, who historically protect springs, rivers, and wells. Largely, these beings have everything to do with water, for good or ill. One hand brings fertility, the other flood. Nonetheless, these protector spirits hold great significance in the religious traditions of both Hinduism and Buddhism, and can be found widely across South and Southeastern Asia, in multifarious forms and settings. [1]

In Ocarina of Time’s Water Temple, these serpents were not many in number, primarily forming the pillars which held hook-shot targets and enshrining crystals that controlled various mechanisms within the dungeon. Here, both outside and inside the spring itself, they are impossible not to notice. On the exterior, five nāgá heads spring forth from the rock above the entrance, carved in good likeness, peering out over the lake. (An odd number of heads represents that the creature is male, while even numbers denote females. Generally speaking, these beings represent fertility, immortality, and protection.) [2] The spirit Lanayru also takes this form, and so it can justly be said that these nāgás are its holy symbol. They appear numerously inside the cavern surrounding the spring, as well as in the room across the water where treasure is stored in a long hallway of encircling nāgás. These spirits are of clear importance within Zoran culture, and their significance has only increased over the centuries.

In Ocarina of Time’s Water Temple, these serpents were not many in number, primarily forming the pillars which held hook-shot targets and enshrining crystals that controlled various mechanisms within the dungeon. Here, both outside and inside the spring itself, they are impossible not to notice. On the exterior, five nāgá heads spring forth from the rock above the entrance, carved in good likeness, peering out over the lake. (An odd number of heads represents that the creature is male, while even numbers denote females. Generally speaking, these beings represent fertility, immortality, and protection.) [2] The spirit Lanayru also takes this form, and so it can justly be said that these nāgás are its holy symbol. They appear numerously inside the cavern surrounding the spring, as well as in the room across the water where treasure is stored in a long hallway of encircling nāgás. These spirits are of clear importance within Zoran culture, and their significance has only increased over the centuries.

Above left: directly inside the entrance to the spring, two nāgá heads can be seen flanking the portal in grey stone.

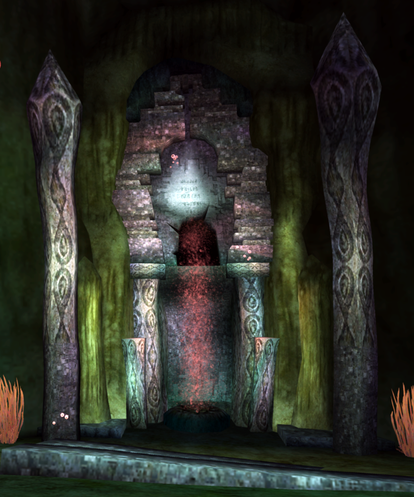

Bottom left: the door at the back of the spring chamber carries a relief of a two-headed serpent, mysterious yet not unrelated to the nāgás seen elsewhere within this shrine. Several serpentine heads extend from the doorway, watching from above.

Bottom right: the back of the farthest cavern, where a gathering of the snakelike guardians watches over a green-lit sanctuary.

Bottom left: the door at the back of the spring chamber carries a relief of a two-headed serpent, mysterious yet not unrelated to the nāgás seen elsewhere within this shrine. Several serpentine heads extend from the doorway, watching from above.

Bottom right: the back of the farthest cavern, where a gathering of the snakelike guardians watches over a green-lit sanctuary.

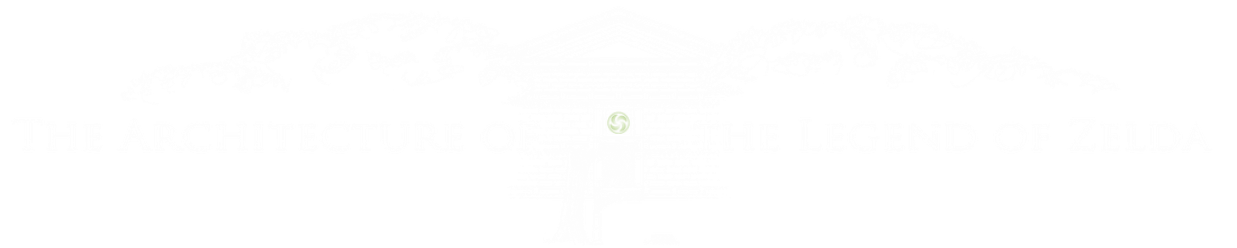

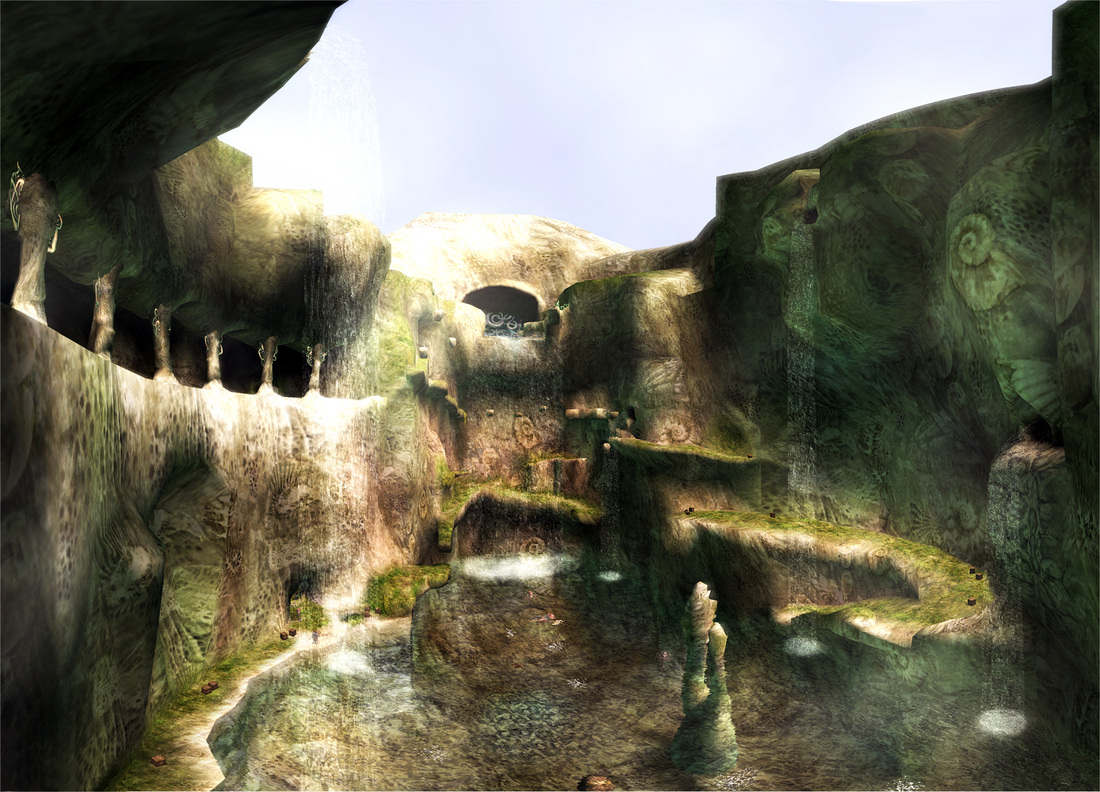

Far up in the mountains near Lake Hylia is the font of Hyrule's water, Zora's Domain. Whereas previous incarnations of the Zoran home have been enclosed, austere spaces little more than caves, this rendition is beautiful, structured, and yet natural. The area directly before the throne room is an enormous sinkhole, open to the skies. Groundwater cascades out of several openings high up in the cliff sides, forming a pool of dazzling clarity below. Natural paths lead upward from the shores of the water, and from here, the fossil remains of colossal ammonites and trilobites, shimmering opalescently with greens and blues, give the cliff walls both history and untold age. A loggia, created by a colonnade of rough stone, sits opposite these fossils, connecting the Domain to various other places within Hyrule. Only the beginnings of Zoran architecture can be seen here in the fluid latticework and ornamentation on the columns, and in the main waterway to the throne room. It seems a common characteristic of Zoran space to be tampered with as little as is possible, using the preexisting stone, caves, and outcroppings to augment their dwellings.

This last chamber is a spacious cavern containing the origins of the river. The chamber focuses upon its beginnings, creating the mouth of a well around the source, from which rise several highly-carved steps leading to the ornate grills which stand between the columns. (In this case, column refers to the meeting of a stalagmite and stalactite, and not anything created by sentient beings, as these appear completely natural). These grills are elaborate, colorful arabesques showcasing the fluid lines and water-plant motifs loved by the Zora. These arabesques form a hallway behind them leading to the throne, which itself is a simple seat. The regal nature of this chair is not to be found in its construction, but derived from the great roots which thrust downward to a point behind the back of the chair. An opening in the natural arcade before the throne grants the ruler an unparalleled view of the spring waters rising from below the ground, and a solitary torch rests within the shallows of the pool. The colors of this room are all cooler hues, reflecting different shades of water in aquamarines, deep blues, algae greens, and purples. As they are the race tied to the element of water, it should come as no surprise that it is the most common feature in their art.

Above can be seen the throne room in its entirety, from the stalactite-columns to the great throne. From there, we see two photos in detail of the rough columns, with branches, roots, and leaves, as well as the throne itself, adorned similarly. Below these two pictures are shown the intricate stone carvings adorning the river's source (abstract, circular designs, predominantly) and the underwater fencing that creates a channel in the river leading downward to Zora's Village. These designs echo the arabesques within the throne room.

The last two pictures show the flow of water at the very beginnings of the river. This is the view granted to the Zoran leader — a channel of stone filled with light or stars, and a cleft in the cliffs proving a mirror of nobility and beauty in the topmost towers of Hyrule Castle.

From its source, Zora River travels swiftly down the mountain, winding its way through cave, canyon, and tunnel, until it reaches its destination in Lake Hylia far below. Lakebed Temple is buried in a multi-level recess at lake bottom. An elevated, sealed doorway pierces the wall on one side of the recess, above which is lazily written the English alphabet in Hylian script. (Apparently the designers could find nothing more profound for this epigraphic feature than to continue on in the same vein of the Gerudo script found within the Spirit Temple, being the alphabet on repeat.) Ten large pillars, shaped like the tentacles of some great beast, rise up from the bed of the lake, forming an elaborate and imposing entry-path to the temple.

|

This right image clearly shows the decorative elements upon the tentacles from the HD remake of the game. The designs appear like connected dewdrops, filled like amoeba with specks and swirls, giving them some semblance to Morpha, the cursed creature from Ocarina of Time's Water Temple.

|

To the left, we see the darkened entrance to this Lakebed Temple, the Zoran holy site wherein dwell the spirits of water. The doorway itself is, apart from the tentacle-like appendages rising from the lake floor, of a natural-seeming, rough-cut stone. The picture directly above shows the approach to the temple.

|

The Water Temple and Lakebed Temple are likely related structures. Whether it is the exact structure of Ocarina of Time or one heavily influenced by it, several similarities show themselves clearly. Even from the beginning, in which the antechamber is reached through an underwater tunnel leading up to the well-mouth entrance of the temple proper, the sameness can be seen. Though the décor is different, and much advanced, the layout and naturalness of the cave system, as well as its location at the bottom of Lake Hylia, profess its true identity. In this initial round room, only the entrance to the deeper parts of the temple has been tampered with; the stalactites have been carved into fluid, falling water, and the platform is covered with green and aquamarine tiles held together with some form of plaster or concrete. Upon these tiles is emblazoned the sacred symbol of the Zora. The torches which light up this room, and indeed this temple, are gold with teal gems, on a standard of red and gold, from which extends an ornate golden arm and mosaic candle holder. While these items of great craftsmanship deeply offset the natural cave setting of most of this temple, most of the chambers have largely been left untouched, their underground waterfalls and raw terracing forming splendid water effects.

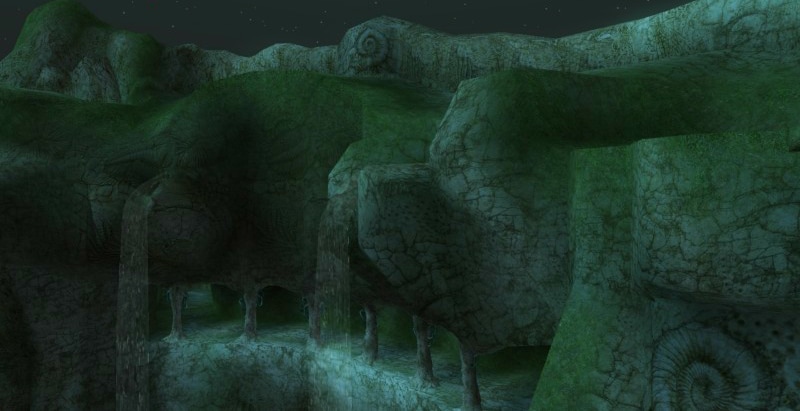

The doors deserve special attention, as they are some of the only things that show a consciousness at work within this sanctuary. In this nearly-pristine cave system, the doors demarcate the bounds of nature and civilization. They give this area a presence that would not be felt without them. And they range from simplistic to ornate in taste. The simplest style carries the Zoran symbol with a metal grill at the bottom which allows water to flow through and out into the central chamber. The door frame is a tiered sculpture which is reflective of those molded stalactites seen in the antechamber and elsewhere in the dungeon. Upon the lintel, two tentacles or jets of water flank a central whirlpool in carved stone.

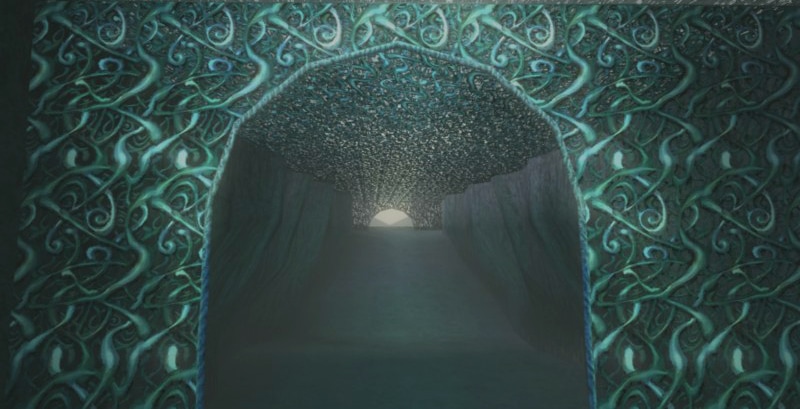

Increasing in grandeur, the doors found leading to, and within, the innermost room are vibrant and ostentatious, featuring many symbols already at play in Zoran architecture. The double doors leading to the central chamber are of a pale stone, into which are carved several types of shells; the ammonites previously seen near Zora's Domain have prominent place on the lower portion of the doors, while the upper portion carries two symmetrical scallop shells. Above this door, as with all other portals herein, can be seen the now-familiar whirlpool device. The most ornate doors are those found within the Staircase Chamber of the temple. While the doors themselves are the same, these are headed by a stone carving of a fish, and are of a beautiful mosaic of glistening blues, purples, pinks, greens, and pale yellows. The doors, which face the cardinal directions, are each done in a different color. The lapidary tentacles of the previous insignia are actually carved in this grouping, flanking the door on either side, reaching toward the animal statue above.

Increasing in grandeur, the doors found leading to, and within, the innermost room are vibrant and ostentatious, featuring many symbols already at play in Zoran architecture. The double doors leading to the central chamber are of a pale stone, into which are carved several types of shells; the ammonites previously seen near Zora's Domain have prominent place on the lower portion of the doors, while the upper portion carries two symmetrical scallop shells. Above this door, as with all other portals herein, can be seen the now-familiar whirlpool device. The most ornate doors are those found within the Staircase Chamber of the temple. While the doors themselves are the same, these are headed by a stone carving of a fish, and are of a beautiful mosaic of glistening blues, purples, pinks, greens, and pale yellows. The doors, which face the cardinal directions, are each done in a different color. The lapidary tentacles of the previous insignia are actually carved in this grouping, flanking the door on either side, reaching toward the animal statue above.

Below: linking the Staircase Chamber to a series of rooms in each direction are bridges with a membranous netting forming walls to either side. The floor of these bridges is made up of large tiles of coral and light blue with delicate mosaics of shells and plant life.

Throughout this entire temple, actually, the true skills of the Zora are manifested in the tiles, mosaics, and pottery-esque feel of the shattered walls. This was very strange to me, initially. A great many walls and barriers within this dungeon are broken, as if they were a vase which had been dropped from some great height. However, with the artistry demonstrated in the purple, green, and azure tiles, along with the mosaics found in the hallways and upon the door frames, perhaps this was purposeful. All of these features imbue this structure with the feeling of antiquity, so that it comes together only slowly — fragment by fragment, as if being pieced into a whole at an archaeological site. It is a very strange visual experience, but it is displayed so subtly, and so elegantly, that it goes almost unnoticed.

Anyone that has ever been to Barcelona, in northeastern Spain, should feel a familiar tug walking through the halls of the Lakebed Temple. Inasmuch as cities can ever be dominated by architects, Barcelona has been carved and shaped by the singular talents and vision of one man: Antoni Gaudí. His architectural projects dominate post cards, brochures, and travel agencies within the country, and are so distinctive as to be instantly recognizable anywhere. When he was alive, his work was a massive amalgam of styles, from Modernism to the Gothic, and certain materials, shapes, and forms dominated his art. [3] Gaudí drew extensively from nature, using organic forms and lines within his buildings as much as was possible; to me, his architecture has always spoken of ocean waves, rivulets of water, and of long, snaking vines. Also pertinent to our discussion is Gaudí's use of mosaic. On or within nearly every structure designed by Gaudí, mosaic works can be found. They cover buildings from Casa Batlló and Casa Milà to entire parks, like Park Güell, his signature naturalistic work. The connection to the Lakebed Temple should be obvious; nearly every crafted facade within the temple is coated in a rough, beautiful mosaic quite similar to the works of Gaudí. Below is Gaudí's Casa Batlló that I think shows an undeniable connection between these two architectural styles; the mosaics in the Lakebed Temple are clearly derivative of this work, and the fanciful columns on this real-world building seem eerily akin to the carved columns and even stalactites found in the early chambers of the temple.

Anyone that has ever been to Barcelona, in northeastern Spain, should feel a familiar tug walking through the halls of the Lakebed Temple. Inasmuch as cities can ever be dominated by architects, Barcelona has been carved and shaped by the singular talents and vision of one man: Antoni Gaudí. His architectural projects dominate post cards, brochures, and travel agencies within the country, and are so distinctive as to be instantly recognizable anywhere. When he was alive, his work was a massive amalgam of styles, from Modernism to the Gothic, and certain materials, shapes, and forms dominated his art. [3] Gaudí drew extensively from nature, using organic forms and lines within his buildings as much as was possible; to me, his architecture has always spoken of ocean waves, rivulets of water, and of long, snaking vines. Also pertinent to our discussion is Gaudí's use of mosaic. On or within nearly every structure designed by Gaudí, mosaic works can be found. They cover buildings from Casa Batlló and Casa Milà to entire parks, like Park Güell, his signature naturalistic work. The connection to the Lakebed Temple should be obvious; nearly every crafted facade within the temple is coated in a rough, beautiful mosaic quite similar to the works of Gaudí. Below is Gaudí's Casa Batlló that I think shows an undeniable connection between these two architectural styles; the mosaics in the Lakebed Temple are clearly derivative of this work, and the fanciful columns on this real-world building seem eerily akin to the carved columns and even stalactites found in the early chambers of the temple.

By Planomenos — Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14990290

|

This picture shows two things very much at odds. While the cogs and gears are in perfect order in stunning golds and blues, the walls between them are fractured, partial, and jagged.

|

As in the Light Spring far above, this strange beast resembles a chimerical nāgá, which wraps around the room, descending from the ceiling, its body a perfect aqueduct to channel water.

|

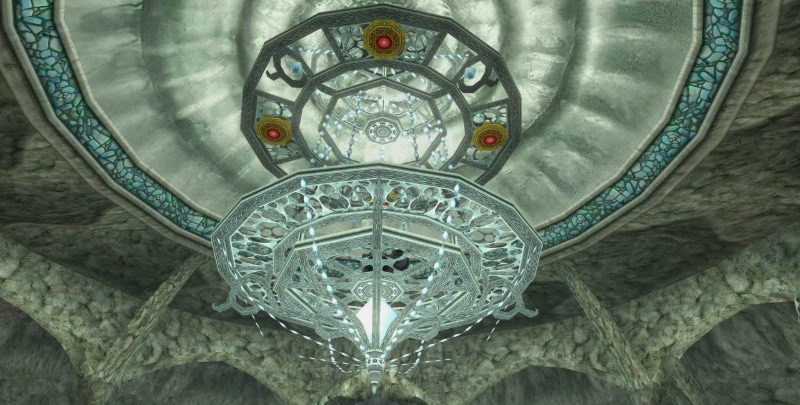

Like the Water Temple of centuries ago, this place also centers around the manipulation of water. But instead of simple changes brought about by music, water is forcibly transported from one area to another through the use of waterwheels, sluices, chutes, and the large central staircase. The main hub of these activities is the Staircase Chamber, which rests above the true temple heart. Fashioned into a cylinder of great depth, encompassed by stories of walkways, the room descends deep into the earth under a shallow dome and opulent chandelier. Juxtaposed against the ancient feel of this site are the technologically-advanced machines which facilitate the changing waters. Levers and handles release torrents of liquid which are carried by gravity through conduits in the floor, turning ornate waterwheels of blue and gold inlay, which act as barriers to different passages and chambers. The streams all reach the center, contributing to the already-existent pool, which eventually enables access to the boss chamber. The whole system is predicated upon these machines being activated by water, and they are thus extremely complex. It is an interesting thought, but it may be that these machines (or their less-elaborate predecessors) were at work within the ancient Water Temple, but it is only in this new structure, with its crumbling walls and newly-built passages, that we are able to see them.

Above: a view from the bottom of the staircase as it carries water into a different section of the temple. The picture on the right shows the ornate chandelier under a shallow dome of what looks like the inside of a shell. A circle of blue mosaic encloses the spiraling dome, and the second story of the chamber can be seen just below, carved in an arcade of simple grey stone.

The final room is oceanic. It is an immense, cylindrical structure filled with murky water that has lain untouched for many years. The massive tiles upon the wall bear symbols of the dungeon above, although the familiar water spiral is here done inversely, facing outward toward the corners of each tile. Sunbursts, or images that look like the points of a compass, can be seen in the lake bed beneath the lake upon the individual drums of the massive columns mired in the sand. Each is segmented rigidly, almost like the armored hide of Morpheel, main calamity of this dungeon. This chamber feels like nothing if not a tomb, as it is profoundly deep, and without exit. For me, falling to the bottom of this dim lake in my iron boots, I felt like Beowulf descending into the marshy, putrid home of Grendel's mother, pulled ever deeper into the unknown.

When the danger is passed, we are once again transported to the sunny shores of Lake Hylia near the Light Spring, to an architectural setting now well-familiar to us. In our adventures, we have discerned several things about the Zora. They are well-attuned to their environment and nature at large; they are an aesthetically-minded society with skilled artists; and they are a deeply spiritual people, secretive yet hospitable. Each in-game civilization is singular unto itself, and it is absolutely incredible that so much can be gleaned not from the creatures themselves, but from what they have created.

When the danger is passed, we are once again transported to the sunny shores of Lake Hylia near the Light Spring, to an architectural setting now well-familiar to us. In our adventures, we have discerned several things about the Zora. They are well-attuned to their environment and nature at large; they are an aesthetically-minded society with skilled artists; and they are a deeply spiritual people, secretive yet hospitable. Each in-game civilization is singular unto itself, and it is absolutely incredible that so much can be gleaned not from the creatures themselves, but from what they have created.

Works Cited:

[1] "Naga." Encyclopædia Britannica. Ed. The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 04 Feb. 2015. Web. 28 Jan. 2017.

[2] Jones, Constance, and James D. Ryan. "Nagas." Encyclopedia of Hinduism. New York: Facts On File, 2007. 300-01. Print.

[3] Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Works of Antoni Gaudí." UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO, n.d. Web. 29 Jan. 2017.

[1] "Naga." Encyclopædia Britannica. Ed. The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 04 Feb. 2015. Web. 28 Jan. 2017.

[2] Jones, Constance, and James D. Ryan. "Nagas." Encyclopedia of Hinduism. New York: Facts On File, 2007. 300-01. Print.

[3] Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Works of Antoni Gaudí." UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO, n.d. Web. 29 Jan. 2017.