Rito Village and the Wild's Frontier

“To those devoid of imagination a blank place on the map is a useless waste; to others, the most valuable part.”

― Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

“The world's big and I want to have a good look at it before it gets dark.”

― Attributed to John Muir, famous Scottish-American Naturalist

― Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

“The world's big and I want to have a good look at it before it gets dark.”

― Attributed to John Muir, famous Scottish-American Naturalist

For me, and perhaps this is just as an American [1], the west always feels, well, a bit wild. And Hyrule feels no different: when I think of the most out-there, hinterlands-feeling locations in Breath of the Wild, my mind goes immediately to the enormous Tanagar Canyon, Tabantha, and the piercing colds of Hebra. As they say, it is a “region of few inhabitants and fewer travelers.” [2] Hebra Province stands in a place apart, cut off from the main body of Hyrule by Tanagar Canyon, an immense gulch which begins just above the Gerudo Highlands and extends nearly to the utmost north, where a single bridge of land connects Hyrule to Hebra above the mystery of the Forgotten Temple. Few signs of civilization exist in this region, mostly ancient, some contemporary; the Ancient Columns in the south present a fascinating enigma, while the Tabantha Village Ruins farther north speak more to a tragedy. The dominant landmarks are the Tabantha Great Bridge — a rapidly-aging wooden suspension bridge at the far south of the canyon —, a few stables, some charming cabins, and numerous rustic windmills that help us attune to the primary element of this region: air. The roads of this region meet near the Rito Stable at the lip of Lake Totori, from which a smaller path springs and wends its way around the southern half of the lake, eventually reaching slowly north to the Warbler’s Nest, Rito Flight Range, and the quaint Hebra Trailhead Lodge. But in this vast land, where snowfields dwarf the living and icy winds gust unchecked from the uncounted mountains, there is one spot that stands out all the more in its stark beauty.

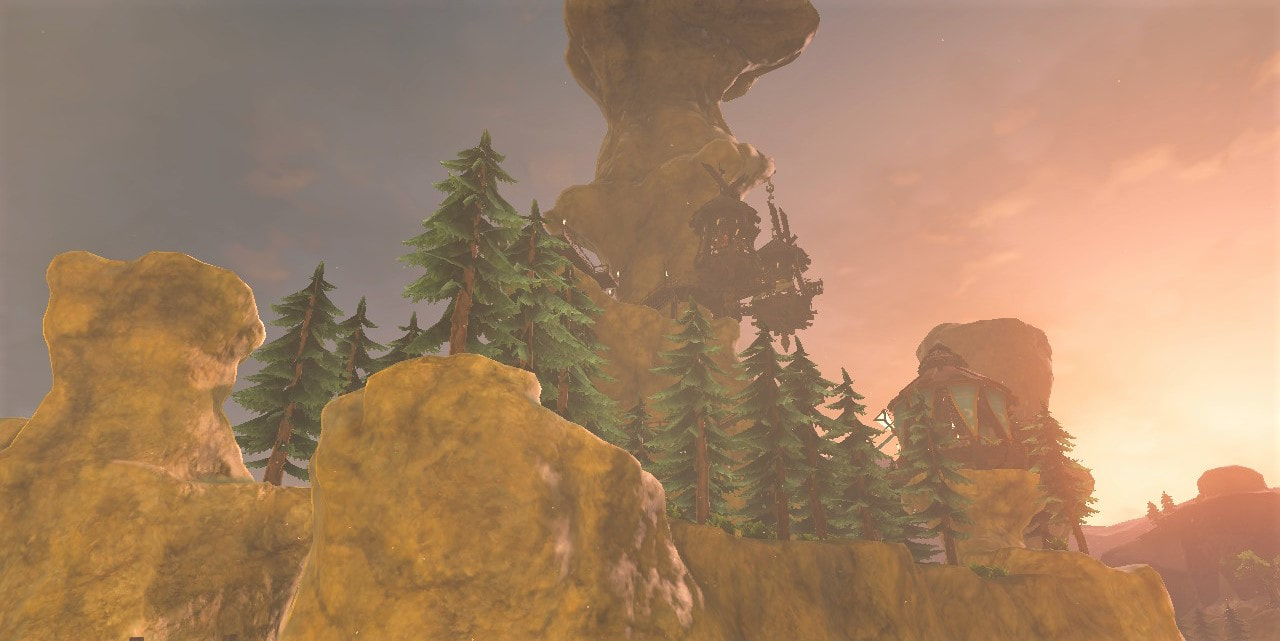

Rito Village is a sight to behold, rising from the middle of Lake Totori on an immense pillar of stone. There are nine islands within the confines of the lake — five smaller, outlying islands, and the main four to the east which, connected as they are by walkways, trace the ascent to the base of Rito Village. The village itself, as we will come to find, is basically a single, linear path which spirals upward, linking the lower levels to the topmost. But we are getting ahead of ourselves. The first thing to attend to, crossing the long wooden bridges from island to island, is just how serene it all is. As the familiar music of past games comes floating in on the air, we further attune ourselves to the wind. And, to me, nowhere is wind so beautiful as when it is blowing through trees — and specifically through conifers.

Rito Village is a sight to behold, rising from the middle of Lake Totori on an immense pillar of stone. There are nine islands within the confines of the lake — five smaller, outlying islands, and the main four to the east which, connected as they are by walkways, trace the ascent to the base of Rito Village. The village itself, as we will come to find, is basically a single, linear path which spirals upward, linking the lower levels to the topmost. But we are getting ahead of ourselves. The first thing to attend to, crossing the long wooden bridges from island to island, is just how serene it all is. As the familiar music of past games comes floating in on the air, we further attune ourselves to the wind. And, to me, nowhere is wind so beautiful as when it is blowing through trees — and specifically through conifers.

There are no deciduous trees this far north in this region, and so we are surrounded by straight and spearlike pines which call to mind a host of mental associations. Chinese poets, painters, and recluses have long been drawn to the pine as a symbol of tenacity, virtue, and individual charm. Lin Yutang writes in his charming The Importance of Living, “Out of the myriad variety of trees, Chinese critics and poets have come to feel that there are a few which are particularly good for artistic enjoyment, due to their special lines and contours which are aesthetically beautiful from a calligrapher's point of view. The point is, that while all trees are beautiful, certain trees have a particular gesture or strength or gracefulness. These trees are therefore picked out from among the others and associated with definite sentiments.” He goes on to talk at some length about the pine tree, noting that it “typifies better than other trees the conception of nobility of manner. . . . The Chinese artists therefore speak of the grand old manner of the pine tree . . .” But what about its manner do we find so charming? It might be a matter of seeing human characteristics bound up in those of trees, human virtue manifested in root, branch, and twig. “I say the enjoyment of pine trees is artistically most significant, because it represents silence and majesty and detachment from life which are so similar to the manner of the recluse. . . . As one stands there beneath a pine tree, he looks up to it with a sense of its majesty and its old age, and its strange happiness in its own independence. . . . Like wise, old men, it understands everything, but it does not talk, and therein lie its mystery and grandeur.” In particular it is the reclusive nature of the pine, standing solitary upon the hill, its roots churning through the stone beneath. “It is this antique manner of the pine tree that gives the pine a special position among the trees, as it is the antique manner of a recluse scholar, clad in a loose-fitting gown, holding a bamboo cane and walking on a mountain path, that sets him off as the highest ideal among men.” [3]

In fact, the pine has long been upheld and revered as one of the “Three Companions of Winter” (岁寒三友), at least since the Song Dynasty. [4] This recurring triadic motif immortalizes those plants which have long drawn the Chinese eye for their hardiness and constancy. As the year ends and most plants fortify their defenses by shedding their foliage, these three remain as companions to those among us humans who must face winter’s cold. But the pine in particular stands out, given its longevity and ability to survive in myriad conditions; due to this, “the pine became considered as the ultimate test of time, symbolizing a wise and brave old person who has withstood and experienced many difficulties.” [5] As a symbol of longevity, the connection is obvious. The connection to virtue may be a bit harder to pin down. Xun Zi, a Confucian philosopher, drew upon these similarities when he wrote that “Even when a gentleman is in dire straits and bitter poverty, he does not lose his way. Although he is tired and exhausted, he does not behave indecorously. In the face of calamity or great difficulties, he does not forget the smallest requirement of his belief. Not until winter comes, do we know the character of pine and cypress trees. Not until [a nation] has encountered difficulty, do we know the character of a virtuous person.” [6] In short, the pine tree does not abandon itself when presented with hardship, but appears all the stronger in adversity, just like a person of virtue, who, when tested, appears to rise above the storm, relying as they are upon their own principles and character.

In fact, the pine has long been upheld and revered as one of the “Three Companions of Winter” (岁寒三友), at least since the Song Dynasty. [4] This recurring triadic motif immortalizes those plants which have long drawn the Chinese eye for their hardiness and constancy. As the year ends and most plants fortify their defenses by shedding their foliage, these three remain as companions to those among us humans who must face winter’s cold. But the pine in particular stands out, given its longevity and ability to survive in myriad conditions; due to this, “the pine became considered as the ultimate test of time, symbolizing a wise and brave old person who has withstood and experienced many difficulties.” [5] As a symbol of longevity, the connection is obvious. The connection to virtue may be a bit harder to pin down. Xun Zi, a Confucian philosopher, drew upon these similarities when he wrote that “Even when a gentleman is in dire straits and bitter poverty, he does not lose his way. Although he is tired and exhausted, he does not behave indecorously. In the face of calamity or great difficulties, he does not forget the smallest requirement of his belief. Not until winter comes, do we know the character of pine and cypress trees. Not until [a nation] has encountered difficulty, do we know the character of a virtuous person.” [6] In short, the pine tree does not abandon itself when presented with hardship, but appears all the stronger in adversity, just like a person of virtue, who, when tested, appears to rise above the storm, relying as they are upon their own principles and character.

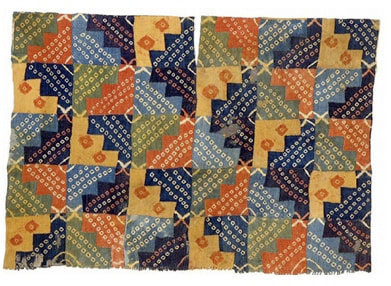

Three Friends of Winter, by Zhao Mengjian (趙孟堅). Song Dynasty, circa 1264. Image in the Public Domain.

So, we see many things in the pine tree, given the human predilection to project our virtues and vices upon the natural world. The pine, to me, while it certainly represents the aged recluse as in Lin Yutang’s writing, also represents the sentry. Pine trees really do stand apart at times, seeming to keep a vigilance even when all their fellow trees have retreated into themselves. Their evergreen nature holds out against the cold, perhaps making sure that Green has some small foothold when cometh spring. But while the sharp-lined conifers give an air of the martial, there is nothing else in Rito Village to suggest defensive measures. The bridges lack the ability to be drawn up against invaders, and there are no gates or guard posts, but only a few guards stalking between the trees on foot. They tread past limpid pools and soft-colored stones, and through the trees we catch glimpses of wooden lamps and decorative gates. Rito society is not particularly decorative; it is a highly-functional architecture, though still prone to some flights of fancy. The gate layout gives the impression of a bird’s wingspan, of feathers extending out against the sky. This symmetrical, three-feather motif carries on in many places around the village, the Rito having written their biology into their architecture. Unlike the other races of Hyrule, which have realistic representations of themselves in art, the Rito have but one representation, and a highly abstract one at that — a crescent-moon bird of prey with three dots as feathers. Why this difference in aesthetics, and where do the Rito take their inspiration?

First, it is critical to note that, unlike most other games in the franchise, Breath of the Wild doesn’t borrow many architectural elements of real-world cultures for use in-game; instead, perhaps more interestingly, they draw upon handicrafts and other artistic modes of expression for architectural inspiration: Jōmon pottery for the Ancient Sheikah, art nouveau jewelry and metalworking for the Zora, mosaics and statuary for the Gerudo, ironworked tools for the Gorons, and textiles and weaving for the Rito. Of course, some cultures (e.g., the modern Sheikah and Hylians) borrow from real-world architecture, but the non-Hylian races in this incarnation of Zelda take inspiration from things that are, at least to me, under-noticed and underappreciated forms of art and artisanship. It is also curious to note that almost every race — Goron, Gerudo, Hylian, Zora — represents itself in statuary: sometimes monumental statuary, as in the case of the Gorons and Gerudo. But the Rito have nothing like this: only a small symbol to denote their presence in Hyrule. Why such a limited symbolic vocabulary? Why so few works of traditional artwork? A few answers immediately flood the mind: it could stem from the Rito’s particular morphology (among the races, they are the only one without hands), but it could also reflect a difference in cultural values. Given the Rito’s relatively short lifespan [7] one might wonder why they wouldn’t go in for statues that could pass down legacies and histories throughout the centuries. Yet not all history needs to be literary or reified in stone to survive. Much history is oral, and perhaps the answer to this mystery is best embodied in Kass, who travels the land in search of lore and story which he can set to song. We know that the Rito “. . . are a people with a tradition of developing expert archers and skilled songsters” [8] and that they “are known for their musical abilities” and “have passed down many legends through the ages in the form of songs or poems” [9], so it may be that they hold their entire cultural legacy in bardic knowledge, relying on minstrels, scops, and skalds to relay their heritage from one generation to the next. There is a deep beauty to this folkway — at least as beautiful as that of the musty tome and the antique scroll.

It seems that the Rito, then, value the ephemeral and that which demands presence in the given moment, apparently forsaking an abiding attachment to past or future. At the very least, they are culturally oriented in ways that ensure that their presence on the earth is a light one. It strikes me that this echoes perfectly their manifestation as birds and their relationship to the air. Unlike their other Hyrulean counterparts, they are not consumed by massive building projects and withstanding the test of time; normally, they spend their days in that most mutable of elements, chasing the wind and scattering the clouds. They tread on earth to sleep and eat, but they are not a people of dirt or clay. Given all this, it is highly unsurprising to find that, alongside song and tale, the Rito’s master passion is archery. Archery, at least at the philosophical or spiritual level of analysis, has two primary components springing from Buddhism and Daoism, respectively. From Buddhism, we pull themes of impermanence and evanescence which culminate in the Japanese aesthetic principle of mono no aware. This “pathos of things”, this being able to appreciate a thing’s beauty because of its transience, could underlie the Rito’s indifference to monumentality and permanence. If things last eternally, are we able to still find them beautiful? In the mindset of mono no aware, things are beautiful precisely because they will not last: their fragility makes them precious, and in being precious, they are transmuted into that which is beautiful. Archery is just one of many Japanese practices — from flower-arrangement to calligraphy — which have spiritual and philosophical orientations. These are activities inseparable from philosophy, especially aesthetics. One does not simply do them as a hobby, but to harmonize with greater elemental forces and to pursue wisdom.

There is also an element of the Dao in archery, most obviously in the form of wuwei (無爲 / 无为), or “non-action”. Just as one “goal” of archery could be said to be an appreciation of the quick flight of an arrow toward its target and the momentary thrum of a bowstring (engaging in mono no aware), so too could another be the spontaneity born of complete atonement with a moment. “Acting spontaneously involves moving beyond the binary of activity or passivity; that is, the world moves the body as much as the body moves in the world.” [10] To peer into spontaneity and see our true nature is a function of any bodily practice, as our bodies act as “a site for cultivating religious-philosophic discipline.” [11] Perhaps the most famous piece on this process, at least in the West, is Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery, and perhaps the most famous line from that book is this: “The shot will only go smoothly when it takes the archer himself by surprise.” Bringing all these aesthetic notions back to our discussion of the Rito, we find that, in place of a vacuum left by the scarcity of tangible Rito artifacts, we are presented with a rich reading of their culture: one predicated on impermanence, spontaneity, and an appreciation of the weightless and fleeting — a true philosophy for birds.

There is also an element of the Dao in archery, most obviously in the form of wuwei (無爲 / 无为), or “non-action”. Just as one “goal” of archery could be said to be an appreciation of the quick flight of an arrow toward its target and the momentary thrum of a bowstring (engaging in mono no aware), so too could another be the spontaneity born of complete atonement with a moment. “Acting spontaneously involves moving beyond the binary of activity or passivity; that is, the world moves the body as much as the body moves in the world.” [10] To peer into spontaneity and see our true nature is a function of any bodily practice, as our bodies act as “a site for cultivating religious-philosophic discipline.” [11] Perhaps the most famous piece on this process, at least in the West, is Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery, and perhaps the most famous line from that book is this: “The shot will only go smoothly when it takes the archer himself by surprise.” Bringing all these aesthetic notions back to our discussion of the Rito, we find that, in place of a vacuum left by the scarcity of tangible Rito artifacts, we are presented with a rich reading of their culture: one predicated on impermanence, spontaneity, and an appreciation of the weightless and fleeting — a true philosophy for birds.

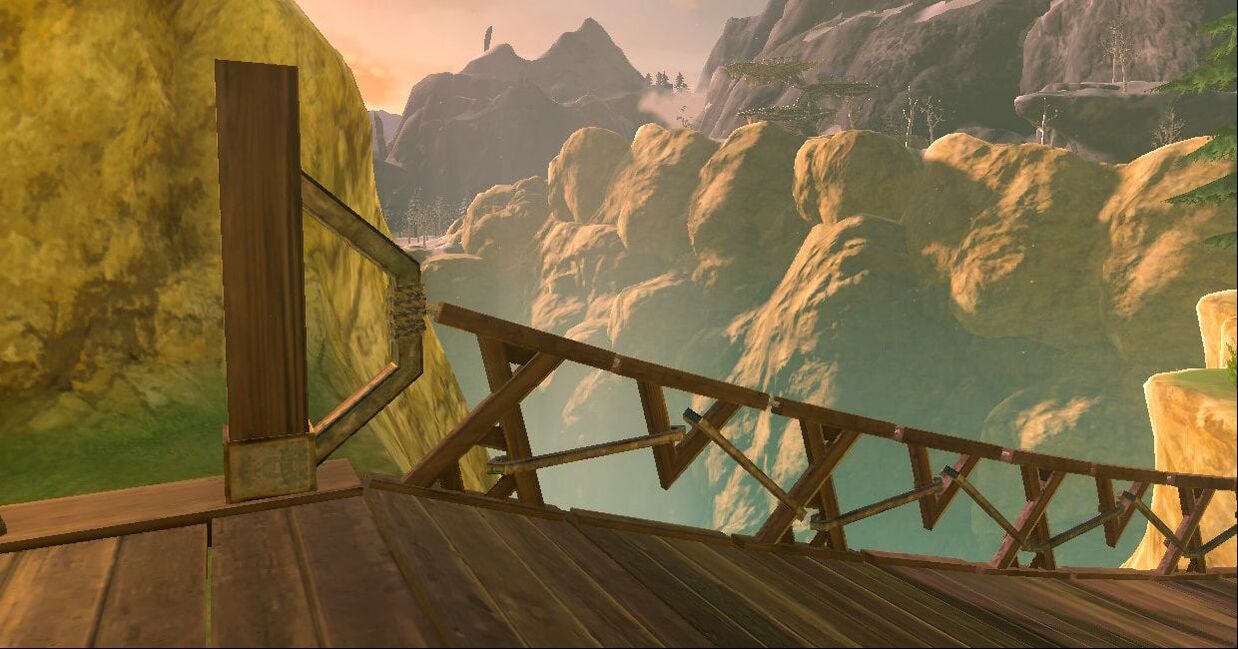

So too in their buildings do we see notions of impermanence, like those structures of the ancient Japanese all built of wood. As we cross the several rope suspension bridges connecting one rock island to the next, we come into contact with the basics of Rito construction and aesthetics. The bridges themselves show a good degree of artisanship, with regular construction and milling; large posts on either side hold down metal supports from which a chain extends through the wooden guardrails. The guardrails feature inverted triangles (the lower of which is a constricted Triforce) and are further held together by metal bars which have been hammered into place at the base. Overall, the bridges appear remarkably sturdy, and have a very natural, rustic beauty born of regularity and simplicity. The wooden signs that guide the traveler bear an arrow created of two abstracted feathers done in wood, while the open, symbolic gateways (as those seen in Kakariko Village or Lurelin Village) rest upon tripod frames, holding up both a symmetrical, though ragged, crest of feathers and a set of lanterns, inverted at the gate’s middle. The tripod supports and upper lintel structure are bound together with cord, while the ends of the wooden boards are painted with two white bands. From afar, it gives the impression of a gate created of large feathers from some bird of prey. There are only a few pieces of Rito construction that feature metal (almost certainly imported from elsewhere), and these are mostly used as stabilizing and anchoring elements. We see metal primarily in four places: on the guardrails of bridges, on the walkways which connect buildings to the stone pillar at the heart of Rito Village, in the rough chimneys upon Rito roofs, and in the massive chains and hooks holding up the cage-like houses. There are also smaller metal braces about, but, for the most part, wood is the dominant material of these structures, reflecting basic Rito aesthetic philosophy.

|

Above: Note the triangular designs and presence of metal.

Right: The lamp-posts I find particularly charming, as they carry both a spirit of whimsy and comfort. Not quite sturdy, some of them lean upon two askew legs, ready to be knocked over by the next breeze; yet, the shape and material warmth do a great deal to calm the wayfarer’s heart. |

As we begin to ascend the winding walkway, passing a lovingly-adorned statue of the Goddess, we get a better sense of the airy quality of this place. There is a constant breeze through Rito Village, though not one overly powerful; while their houses are anchored to the central walkway by small bridges and weighted down at the bottom by heavy pieces of metal or stone, they do not seem to be much at risk, and none of the light-weight objects in the open-air houses ever seems to get blown away. At least lower to the ground the airs are gentle. The developers describe the Rito’s home as being “hung” upon the sides of the central stone pillar, going on to say that “Airy abodes and shops constructed from lumber are affixed to the side of the column and connected by a spiraling staircase. The upward construction of their village is unique to the flight-capable Rito, and there are many other aspects of Rito Village that are inconvenient to the other races of Hyrule, so they get few visitors.” [12] This verticality was a chief design element in the village’s conception, given the Rito’s relative freedom from gravity; but their avian nature also provided the inspiration for the colorful textiles found throughout the town. [13] This connection comes to us through the condor and the civilizations of the ever-compelling Andes Mountains.

Like the Andes, the pillar of Lake Totori stands stark against the sky. And just as the condor captured the attention of Andean peoples, so too do the Rito capture the essence of the Andean spirit. Now, saying “the Andes” is a bit like offhandedly talking about Russia — it’s an enormous tract of land full of diverse climes, histories, and peoples. For the purposes of our little discussion, we’ll be focusing primarily on the civilizations of Peru, though we might tread a bit further afield into places like Ecuador and Bolivia.

The Cordillera del Paine in the Torres del Paine National Park, Southern Chile. This massif is located in an eastern spur of the Andes Mountains. Image Credit: Mpazmarzolo, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Along with the later-developing Olmec culture in Mesoamerica, the earliest civilization to arise in the Americas was that of the Norte Chico (also called the Caral-Supe civilization) along the Peruvian coast between the fourth and second millennia BCE. These two cultural powerhouses are considered by many to rank among the six “Pristine Civilizations”, being those complex, stratified societies that arose endogenously from Neolithic cultures without the influence of migration or cultural exchange. [14] There has been much debate as to where the earliest elements of Andean civilization originated; for a long time, the mother site was considered to be at Chavín de Huantar in the central highlands of Peru. But archaeological evidence from Caral shocked many when radiocarbon techniques gave a date for a major urban center in the Americas nearly two-thousand years older than that of the Olmecs. [15] Beyond its age, archaeologists were staggered by its size and scope; Caral, which covered roughly 1,500 acres, was home to immense terraced pyramids made of earth and other monumental structures, and had a population of thousands. [16] If we compare this to other civilizational development at the time, we find that the Norte Chico civilization was building its pyramids during the same period as the ancient Egyptians were constructing theirs. And while other cities in the region are now vying as contenders for title of “oldest city in the Americas”, they are all bound together as members of the Norte Chico civilization, each with their own monumental or large-scale communal architecture. In the end, we may content ourselves with the fact that the cradle of Andean civilization likely rests somewhere in the coastal regions of Peru. And while all of these “pristine” civilizations are fascinating in their own right, that of the Norte Chico is exceedingly odd for several reasons: its development happened quickly, over the course of hundreds of years, instead of millennia; it seemingly lacked all ceramics [17]; it may have been primarily a marine economy, and not an agricultural one [18]; and, unique among these early civilizations, it lacked a traditional system of writing, though it may have encoded information into khipu (or quipu) for communication purposes. [19]

A wide shot of the ruins of Caral in the Supe Valley of Peru about 23 kilometers from the coast.

Image Credit: I, KyleThayer, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Image Credit: I, KyleThayer, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

It is interesting that the people of the Norte Chico should encode language through weaving, but it is ultimately unsurprising, given what we know of their artistic focus; they left very little visual art but for their architecture and, most famously, their textiles. In fact, textiles, as we will see, have been the dominant form of artistic expression of the Andean peoples for millennia. [20] And we have many well-preserved textiles from the south coast of Peru, where it is extremely dry, some examples showing “over a hundred shades of color . . . and a great diversity of materials — cotton, wool and even human hair.” [21] Just as the Andean peoples crafted some of the most beautiful textiles in the world, so too do we see the Rito following suit. Nearly every home in Rito Village features decorative textiles alongside its more functional pieces. We see vivid, all-natural earth tones predominate among the dyes: light and dark greens, cornflower blue, turquoise, many different ochres, orange, and cream-white. A few things become immediately obvious across all Rito textiles: lines are almost always rectilinear [22], symmetry is consistently valued, and geometric figures obtain.

It should be noted that there are three primary symbols among the Rito: a crescent moon, an abstracted bird, and, perhaps most commonly, a chakana, or Inca Cross. The word chakana takes its roots from the Quechua word for bridge, stair, or intersection; the first use of the chakana symbol is unknown, though we can estimate a rough age from an obelisk at Tello en Chavín at about 3000 years. It is found in many places, especially across the Inca Empire, and could possibly have represented many philosophical or astrological notions, expressing dualities, the order of the universe, or certain constellations. [23] However, it is a controversial symbol, as we have no guide to interpret it, nor a clear story of its origins. There are even those who believe it to be a relatively recent invention in terms of its spiritual trappings. In short, it is uncertain what the chakana represents, but two things can be said about it: it is definitively Andean, and it is very pleasing to the eye. Because of this latter reason (as we learn next to nothing about Rito mythology or symbology in the game), we see the chakana upon the huge rugs splayed out in the middle of homes and shops, upon tablecloths and doilies, hung over bannisters, and on blankets, hammocks, and pillows. (This calls into doubt its sacred nature to the Rito, at least.) The crescent moon image can be seen most obviously on the large banners stretched between houses and shops, where it is suspended between two other angular designs which may represent the encircling mountains, the pines at the foot of their village, or nothing at all. As has been noted, the only Rito-centric symbol we see is that of an abstracted bird, scattered among the textile landscape. It consists of a crescent moon representing the wings of a predatory bird with a small angular protrusion in its middle representing a head and beak; opposite the head on the outer ring of the crescent moon are suspended three dots, representing tail feathers. Like many Andean cultures, and deeply unlike Mesoamerican styles, the Rito shy away from depictions of themselves in art, preferring to lose themselves in geometric abstraction. [24]

It should be noted that there are three primary symbols among the Rito: a crescent moon, an abstracted bird, and, perhaps most commonly, a chakana, or Inca Cross. The word chakana takes its roots from the Quechua word for bridge, stair, or intersection; the first use of the chakana symbol is unknown, though we can estimate a rough age from an obelisk at Tello en Chavín at about 3000 years. It is found in many places, especially across the Inca Empire, and could possibly have represented many philosophical or astrological notions, expressing dualities, the order of the universe, or certain constellations. [23] However, it is a controversial symbol, as we have no guide to interpret it, nor a clear story of its origins. There are even those who believe it to be a relatively recent invention in terms of its spiritual trappings. In short, it is uncertain what the chakana represents, but two things can be said about it: it is definitively Andean, and it is very pleasing to the eye. Because of this latter reason (as we learn next to nothing about Rito mythology or symbology in the game), we see the chakana upon the huge rugs splayed out in the middle of homes and shops, upon tablecloths and doilies, hung over bannisters, and on blankets, hammocks, and pillows. (This calls into doubt its sacred nature to the Rito, at least.) The crescent moon image can be seen most obviously on the large banners stretched between houses and shops, where it is suspended between two other angular designs which may represent the encircling mountains, the pines at the foot of their village, or nothing at all. As has been noted, the only Rito-centric symbol we see is that of an abstracted bird, scattered among the textile landscape. It consists of a crescent moon representing the wings of a predatory bird with a small angular protrusion in its middle representing a head and beak; opposite the head on the outer ring of the crescent moon are suspended three dots, representing tail feathers. Like many Andean cultures, and deeply unlike Mesoamerican styles, the Rito shy away from depictions of themselves in art, preferring to lose themselves in geometric abstraction. [24]

|

Above: Nasca-Huari Unku with staggered, linear designs —

Lima Art Museum, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Right: Wari tunic, Peru, 750-950 CE, Image in the Public Domain. |

Above Left and Right: We see the ample use of feathers in decorating, hanging from rafters near the ceiling, used as tassels on pillows and hammocks, acting as bookmarks, and suspended from shelves. And while Inca textiles were rarely embroidered, occasionally “feathers were imported from the jungle and sometimes sewn into large shirts and capes.” [25]

|

Before we discuss Rito architecture proper, I wanted to first mention Rito ceramics; while the Norte Chico were fairly unique in their aceramic existence, ceramics of course did burst upon the South-American scene eventually, and became an incredibly rich and varied pursuit. Rito pottery is fairly simplistic in nature, though showy uses of polychromy and angularity keep it from being uninteresting. As in textiles, the Rito have shied away from representational pottery, except for the three-feather motif which rests just below the lip of many ceramics. Otherwise, they are marked by geometric patterns and broad bands of vibrant color. As with Inca sculpture, there is a broad feeling of horizontality to Rito pottery, and it is all rather utilitarian. The Dictionary of Art has this to say about Inca ceramics:

“Pottery was standardized in form and decoration, well-designed and well-proportioned but repetitive. . . . All ceramic shapes, whether utilitarian or ceremonial, are predominantly functional and include aryballos jars, plates and flat dishes, jugs and bowls, and large jars for storage. . . . Decoration was organized in zones of parallel bands: continuous triangles or diamonds were used for necks and rims; crosshatching was executed in vertical bands on bodies and horizontal bands on bowls and the insides of plates.” [26]

“Pottery was standardized in form and decoration, well-designed and well-proportioned but repetitive. . . . All ceramic shapes, whether utilitarian or ceremonial, are predominantly functional and include aryballos jars, plates and flat dishes, jugs and bowls, and large jars for storage. . . . Decoration was organized in zones of parallel bands: continuous triangles or diamonds were used for necks and rims; crosshatching was executed in vertical bands on bodies and horizontal bands on bowls and the insides of plates.” [26]

In the picture to the left above, near the Goddess Statue, we see some of the more decorative and embellished ceramics of the Rito; these elevated techniques may mark them apart as ceremonial or religious vessels, as opposed to the more simplistic ones on the right.

All of these features can be seen in Rito wares, in the parallel bands of color, in the triangular patterning, and in the proportions. Yet not all Andean pottery was so, shall we say, simplistic. The Moche, or Mochica, had zany, complex, and eye-catching pottery in shapes both representational and functional, with depictions of war, weaving, and, very commonly, sex. [27] At Tiahuanaco, figures of pumas, human beings, and condors can easily be recognized. [28] Condors, both to the Andean peoples and to the developers of Breath of the Wild, are extremely pertinent to our discussion. Most obviously, the Rito were based upon predatory birds. [29] But we get another glimpse into their inspiration, as one of the developers admitted to designing aspects of the Rito with the song “El Condor Pasa” playing on repeat in his head. [30] The condor is the largest bird of prey in the world, and was depicted in art from the Andes to southern California, where it can be seen in Condor Cave in the San Rafael Wilderness. But the most spectacular condor representation can be found among the Nazca lines near Peru’s south coast — the most extensive geoglyphs we have yet discovered. Considered to have been created by the Nazca culture somewhere between 500 BCE and 500 CE, these immense symbols are fundamentally mysterious in origin and meaning (and theories abound as to why they exist), and are comprised of patterns of “ruler-straight lines and geometric forms (by far, the most numerous), human, floral, faunal, and hybrid forms.” [31] Their method of making was fairly simple: by removing surface dirt, their creators exposed ground of a different color, thus yielding what is called a negative geoglyph (made via a subtractive process). [32] Alongside the condor depiction, which Anthony Aveni has noted appears as the shadow of a condor soaring overhead [33], there are pelicans, hummingbirds, a fish, a spider, a monkey, lizards, an insect, and, most astonishingly, a 500-yard/450-meter frigatebird, whose beak alone measures 300 yards/270 meters. [34]

|

A massive representation of the condor within the sprawling system of Nazca Lines in southern Peru. The condor measures 440 feet, or 134 meters. Image Credit: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

|

A Nazca bowl from the 2nd-4th centuries depicting raptorial birds decapitating human beings. Image in the Public Domain.

|

The condor can be seen elsewhere in human architecture, famously on the Gate of the Sun in Tiahuanaco built by the Tiwanaku culture, an Andean civilization of Bolivia that grew up around the shores of Lake Titicaca, the largest lake in South America, and considered to be the highest “navigable lake” in the world at an elevation of 12,507 feet (3,812 meters). The iconography of the Tiwanaku was highly influential throughout the Andes, associated with other cultures such as the Inca and Wari, and some of the most stunning iconography is found upon the Gate of the Sun. It is covered with bas-reliefs of pumas and condors, and these geometric representations can be found in many other locations throughout the Andes Mountains. [35] The gate features a great many anthropomorphic figures with condor heads, all gazing at a central being which is one of the most mysterious figures in Andean culture. “At the center of this frieze is a figure known to most scholars as the Sun God. It has anthropomorphic features in contrast to the deities in Mesoamerica. The head is surrounded by rays which indicate that this figure is a personification of the sun. Representations of puma and condor also play an important role in this relief. Traces of tears in the form of puma fall from the eyes of the central figure, and some of the rays around the head begin as puma heads. The deities hold staffs (rays) in their hands which end as condor heads. In addition there are forty-eight subsidiary figures all hurrying toward the main figure. They are partly human and partly animal, with masks of predatory animals and birds.” [36] This deity is also referred to as the Gateway or Staff God, and was believed to be a god of storms, dealing out rain, thunder, and lightning. [37] A powerful and clear connection can be drawn here to the Cliffside Etchings at the Cliffs of Ruvara leading to the Gerudo Highlands. Though these are far-removed from Rito Village, the design itself could’ve come directly from the Andean highlands. An updraft of wind carries Link close to the etching, and when he is near, he can shoot a shock arrow at the center (recall the elements of the Staff God), causing a Shrine to appear. The etching itself consists of what appears to be a solar motif at the center acting as a bullseye, surrounded by four birds of prey in white and four yellow lightning bolts all racing toward the sun. This combination of elements links the Staff God, who deals in lightning, to the condor, which is the sun personified. This glyph, one of the stranger ones in Hyrule, suddenly makes sense when viewed from a perspective external to the game. The Andean cultural realm is rife with such depictions, and it is a welcome sight to have such images engraved upon the mountains of Hyrule.

A close-up view of the central portion of the Gate of the Sun depicting the Sun or Staff God and various anthropomorphic beings. Image Credit: Dennis Jarvis from Halifax, Canada, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, Wikimedia Commons

The Cliffside Etchings at the Cliffs of Ruvara at the feet of the Gerudo Highlands.

The condor may also be seen at Chavín de Huantar in Peru’s northern highlands. The sculptural style at Chavín is odd, to say the least, and it is known that ritual sacrifice was practiced there, perhaps alongside ritual cannibalism; this insanity seems to be reflected in both architecture and sculpture. The most famous artifact to have been unearthed at Chavín is called, simply, the Great Image (or Lanzón), and it is a truly unsettling piece of imagery. (I won’t go into things here, but please do look it up.) The art of Chavín is highly protean, and very little is overtly clear. It is well-known that priests there would use psychotropic drugs, and so it is rather unsurprising that the architectural and sculptural images should bear some of the hallmarks of a trance state. Distinctive images of the condor have been contested by some (some believing that the bird of prey is an eagle [38]), because we really only have the general contours of a bird, and so the image is highly ambiguous. Further, “interchangeable parts of bodies and multiple points of view complicate the iconography. We may guess that the clustering of the attributes of jaguar, condor, and serpent was meant to personify daemonic forces of nature.” [39] In all, it is a confusing picture, but one well worth the time of scholars and archaeologists.

Throughout these last paragraphs, we have seen that the condor was highly venerated in multiple Andean civilizations. While not an overly-attractive bird, it is certainly stately and majestic from afar — it does seem a true lord of the sky. But what are its symbolic meanings? In many ways, it is “the embodiment of indigenous Andean identity and focus of cosmological beliefs” ranging from ancestor god or a form adopted by mountain spirits to an animal invoked by humans during rituals. [40] It has been associated with the sun deity, seen as a deity of the upper world, and even today is the national symbol of many South-American countries. And the sacral nature of the condor was not just displayed upon architecture, but in pottery, metal-working, and textiles, which ties us back to the Rito. The Rito share a complex relationship to Andean culture, having sprung partly from worship of the condor, and although their architecture is a far cry from Norte Chico, Chavín, or Machu Picchu, their form has graced multiple Andean art forms for millennia. And in homage to their Andean roots, we see the Rito as fine weavers and potters, which hearkens back to their real-world origins. The two cultural realms, Andean and Rito, reflect and complement one another admirably, and it is a lovely picture once we delve beneath the surface of what Breath of the Wild has given us.

Throughout these last paragraphs, we have seen that the condor was highly venerated in multiple Andean civilizations. While not an overly-attractive bird, it is certainly stately and majestic from afar — it does seem a true lord of the sky. But what are its symbolic meanings? In many ways, it is “the embodiment of indigenous Andean identity and focus of cosmological beliefs” ranging from ancestor god or a form adopted by mountain spirits to an animal invoked by humans during rituals. [40] It has been associated with the sun deity, seen as a deity of the upper world, and even today is the national symbol of many South-American countries. And the sacral nature of the condor was not just displayed upon architecture, but in pottery, metal-working, and textiles, which ties us back to the Rito. The Rito share a complex relationship to Andean culture, having sprung partly from worship of the condor, and although their architecture is a far cry from Norte Chico, Chavín, or Machu Picchu, their form has graced multiple Andean art forms for millennia. And in homage to their Andean roots, we see the Rito as fine weavers and potters, which hearkens back to their real-world origins. The two cultural realms, Andean and Rito, reflect and complement one another admirably, and it is a lovely picture once we delve beneath the surface of what Breath of the Wild has given us.

But it is time to return to Rito Village and see what other architectural details await us. It has been said that the houses of the Rito have been hung upon the monolith at the center of their village, and this is quite literally true: most Rito structures, apart from one gazebo at the village entrance and a few houses and shops, are suspended from the stone pillar via a sturdy metal hook and chain, reinforcing the image of their homes as birdcages. I must say that I have fallen quite in love with these houses, even as they are probably unfit for human life (given their open-air nature and exposure to the elements) [41]; they are charming buildings which are equal parts whimsical and pragmatic. The roofs and base structures are highly redolent of nests, being composed as they are of rough-laid pieces of wood which jut out much like twigs and pieces of straw in a real bird-nest. The wing or feather motif that we have seen before (even hinting back to the katsuogi found in Kakariko Village) further decorates the rooftops of Rito houses, standing beside strangely-bent chimneys, wind vanes, and, occasionally, a small clerestory. The houses are built using eight or twelve large beams, angled at a point near the base, resulting in a taper at the roof. These beams are quite large, seemingly taken from single trees; they are painted, and often festooned with banners, kite-shaped cloths, and other textiles. These do some work in blocking the wind at this altitude, but cannot be said to be primarily for that purpose — likely, they are decorative, as the Rito do not mind the cold. [42]

Across Rito Village, we also see textiles driving small weather vanes, each blade supporting a small “kite” of navy blue with cream edges and the symbol of the Rito. These have the benefit of showing the direction of the wind — critical for a people of the air.

The rafters inside support lanterns, hammocks (the Rito sleep quite close to the ceiling, but for the little ones), and are frequently decorated with feathers suspended from strings. Inside, we are afforded ever-incredible views of distant mountains, forests, and the lake beneath us. And the textiles and warm wood give a deep impression of home. The furnishings cannot be said to be advanced, but they are fairly distributed among the Rito, and seem to all come from a common source. Each home and shop has its share of small tables, bookshelves and books, ceramics (vases and dinner-ware), hammocks or beds, throw-pillows, rugs, and small chests. At the center of many homes is a cooking fire around which stones have been arranged to prevent an errant spark from catching fire to the wood. Walking up and up the spiraling wooden planks of the village, we also find several landing platforms that drop off precipitously over Lake Totori. Here we find more weather vanes and a larger rendition of the Rito symbol, this time with extended wings, done in the same three-feather pattern as elsewhere. And, once Kass has come home to roost, we can find him here with his children, performing and carrying on the bardic tradition with the next generation.

Note the homey aspects above: the warm wood, cheerful textiles, and the small marks of a Rito child drawing flowers upon the walls.

Yet another tradition than the bardic plays out in Rito culture, and that is the cult of the warrior. Huck, a member of the village, tells Link that “all Rito males are urged from birth to become honorable warriors” like Revali, who is held as the paragon of Rito martial skill. The Rito are known to weave their own plumage into their weapons, and they have created a monument to Revali in the largest landing platform in the village; from the landing, one can head immediately to the Flight Range, which rests at the foot of the Hebra Mountains. It was created at Revali’s request for the training of Rito warriors, as the constant updraft in this canyon allows the Rito to practice their marksmanship while airborne. [43] The Flight Range is littered with a number of practice targets and is an architectural manifestation of Rito values — along with the sung word, they value the strung arrow. We see a fascinating parallel here with Moche culture, which depicts “raptorial birds . . . portrayed as warriors . . . handl[ing] shields, maces, and tumi knives.” [44] Other birds appear in combat scenes, as well, but chiefly these birds of prey, much like the Rito, who value the path of the warrior above all for their males.

It seems we have explored most of the paths left for us by the game developers. We now have a good picture of the inspirations for the Rito, how they were inspired by the Andean peoples, and how the Rito, in turn, do homage to them. The one thing that stands apart, strangely, is Kass, the most worldly and familiar of all the Rito. He alone is not the warrior, is not the typical bird of prey, modeled as he is after the blue-and-yellow macaw. But even his presence is accounted for in the Andean realm, albeit indirectly. Bird feathers were precious in Andean societies, and merchants of old “traded brilliantly colored parrot and macaw feathers in long-distance networks . . . where they adorned the sumptuous garments of rulers and kings.” [45] And as this last piece of imagery locks into place, the culture springs to life and escapes us, leaving us with a single impression both beautiful and austere: a lone bird circling far overhead, and the world below trying to capture its shadow.

Notes and Works Cited:

[1] Sorry to my fellow continental Americans (especially the Brazilians among you — I know that you guys are particularly touchy about this), but there’s just no other good demonym for people from the United States . . .

[2] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 305. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

[3] Lin, Y. (1998). The Importance of Living, pp. 295-7. Quill, Willam Morrow.

[4] Three friends of winter | Chinese Art Gallery | China Online Museum. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2021, from http://www.chinaonlinemuseum.com/painting-three-friends-of-winter.php.

[5] Pine Painting | Chinese Art Gallery | China Online Museum. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2021, from http://www.chinaonlinemuseum.com/painting-pine.php.

[6] Wang, Y. (2018, March 1). The Moral Connotations of Pine and Cypress Trees. SSCP. Retrieved October 27, 2021, from http://www.csstoday.com/Item/5302.aspx.

Here’s another lovely article about pine trees, if the spirit so moves you.

[7] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 400. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

[8] Ibid., p. 125.

[9] Ibid., p. 131.

[10] Parkes, G., and Loughnane, A. (2018, December 4). Japanese Aesthetics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved October 27, 2021, from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/japanese-aesthetics/.

[11] Ibid.

[12] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 305. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

[13] Ibid., p. 307.

[14] There are always naysayers in the “groves of academe”, and some scholars enumerate other examples of “pristine” civilizations while still others deny the entire label as preposterous — how can any culture arise “independently”? What makes these societies in any way special? What makes this sort of development more precious than the societies of Neolithic peoples? But, to be honest, I think such scholars are throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Civilization is a very special thing: from decentralized, nomadic or hunter-gatherer tribal societies to those marked by agriculture and domestication, social stratification (and the specialization of labor), urban centralization, complex governance, and, most holy of holies, symbolic communication — such a jump demands some attention, if not respect. We can debate the relative merits of any of these aspects of civilization til the cows come home, but let us at least acknowledge that something special has taken place!

[15] Smithsonian Magazine. “First City in the New World?” Smithsonian.com, 1 Aug. 2002, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/first-city-in-the-new-world-66643778/.

[16] Betz, Eric. “Is Caral, Peru, the Oldest City in the Americas?” Discover Magazine, 2 Feb. 2021, https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/is-caral-peru-the-oldest-city-in-the-americas.

[17] Haas, Jonathan, and Winifred Creamer. “Crucible of Andean Civilization.” Current Anthropology, vol. 47, no. 5, 2006, pp. 745–775., https://doi.org/10.1086/506281.

[18] Moseley, M. E. (1975). The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization. Menlo Park: Cummings Publishing Company.

This theory has seemingly been refined and criticized for decades. See for a good overview: Beresford-Jones, D., Pullen, A., Chauca, G. et al. Refining the Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization: How Plant Fiber Technology Drove Social Complexity During the Preceramic Period. J Archaeol Method Theory 25, pp. 393–425 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-017-9341-3

[19] Mann, Charles C. “Unraveling Khipu's Secrets.” Science, vol. 309, no. 5737, 2005, pp. 1008–1009., https://doi.org/10.1126/science.309.5737.1008.

[20] Bushnell, Geoffrey H.S., and John V. Murra. “Andean Civilization.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/pre-Columbian-civilizations/Andean-civilization.

[21]“In contrast to the north coast of Peru, it never rains on the south coast. Accordingly textiles have endured here over thousands of years completely intact. In the years from 1925 to 1930 two large burial-grounds in the middle of the desert were excavated, Paracas Cavernas and Paracas Necropolis, in which a number of mummies were found. These had remained intact, thanks to the dryness of the climate, just like the woven fabrics in which they were wrapped. Additional fabrics and ceramic and precious metal objects were added to these woven textiles as burial offerings. While the textiles of Paracas Cavernas must be attributed to the pre-classic period and are in part coarsely woven, those of Paracas Necropolis are among the most beautiful and the richest found in America and perhaps in the whole world. Over a hundred shades of color were used and a great diversity of materials — cotton, wool and even human hair. The creators of these textiles are still unknown. Since the places where the burial enclosures are situated seem to have been uninhabited it is generally thought that corpses were transported there from far away. The similarity of some of the Paracas motifs to those of the Nazca valley a hundred kilometres further south indicates that the dead came from there.”

Katz, Friedrich. “The Civilizations of the Middle Andes.” The Ancient American Civilizations, pp. 105-6. Castle Books, 2004.

[22] On rectilinearity: “The technical requirements of the loom further restrict the designer: large curvilinear forms are generally impractical.”

On dyes: Colors used at Cavernas number only about 10 or 12 different shades, mostly browns, reds, yellow-oranges, blue-greens, and natural whites. In Necropolis and Nazca embroideries, we can see many more colors, around 190 in total.

Kubler, George. The Art and Architecture of Ancient America: the Mexican, Maya and Andean Peoples, p. 293. Penguin Books, 1962.

[23] Giovanetti, Marco, and Sofía Silva. “La Chakana En La Configuración Espacial De El Shincal De Quimivil (Catamarca).” Estudios Atacameños, vol. 66, 2020, pp. 213–235., https://doi.org/10.22199/issn.0718-1043-2020-0052.

[24] “The anthropomorphic or humanist bent of all Mesoamerican expression is carried by innumerable representations of the human figure. In the Andes a humanistic style appears only intermittently, as in Colombia and Ecuador, or on the north coast of Peru; elsewhere the human figure is subjected to complex deformations tending either to the emergence of monster-like combinations or to the dissolution of the human form in geometric abstractions. Throughout the Andes a dominant concern for technological control over the hostile environment is apparent.” [Emphasis mine.]

[25] “Inca.” The Dictionary of Art, vol. 15, pp. 163-4. Grove, 1996.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Seriously, get a look at some of this stuff (potentially not safe for work): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moche_culture#/media/File:Fellatiomoche.jpg

[28] “The Classic Tiahuanaco painted wares comprise handsome cups of concavely flaring profile, as well as libation bowls which are squat, wide versions of the cups. Both are painted in as many as five colours on a red slip with heavy black outlines surrounding the areas of local colour. The figures of pumas, human beings, and condors in profile are clearly delineated and easy to recognize.”

“The style of Tiahuanaco belongs to the Andean tradition of conventional signs ordered more by semantic needs than by mimetic relationships. It conveys information about ideas rather than pictures of things, and in this it resembles the art of Chavín, although major differences separate the two styles. Chavín objects are curvilinear and asymmetrical; those of Tiahuanaco are rectilinear and balanced. Chavín carving recalls woodworking and hammered metal; Tiahuanaco art evokes textile and basketry techniques.” [Emphasis mine.]

Kubler, George. The Art and Architecture of Ancient America: the Mexican, Maya and Andean Peoples, pp. 309-10. Penguin Books, 1962.

[29] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 129. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

[30] Ibid., p. 307.

[31] Werness, Hope B. The Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism in Art, pp. 294-5. Continuum, 2004.

[32] Geoglyphs can also be “positive”, created by an additive process such as an arrangement of stones or other materials to create images. Examples of this are the Cerne Abbas Giant near Dorset, England, which features chalk rubble, or the Great Serpent Mound in Ohio, USA, which is an effigy mound of piled earth.

[33] Werness, Hope B. The Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism in Art, p. 294. Continuum, 2004.

[34] Ibid., p. 295.

[35] Katz, Friedrich. “The Civilizations of the Middle Andes.” The Ancient American Civilizations, pp. 243-4. Castle Books, 2004.

Also: “A number of the motifs of this Gateway of the Sun, especially the geometric representations of puma and condor heads, recur with few variations over the entire Andean region.” (Ibid., p.109)

[36] Ibid., p. 109.

[37] Staller, John E.; Stross, Brian. Lightning in the Andes and Mesoamerica, Pre-Columbian, Colonial, and Contemporary Perspectives, p. 86. Oxford University Press, 2013.

[38] Werness, Hope B. The Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism in Art, p. 84. Continuum, 2004.

[39] Kubler, George. The Art and Architecture of Ancient America: the Mexican, Maya and Andean Peoples, p. 244. Penguin Books, 1962.

[40] Howard-Malverde, Rosaleen. “Between Text and Context in the Evocation of Culture.” Creating Context in Andean Cultures, Oxford University Press, New York, 1997, p. 16.

Note: The author here also goes on to state that perhaps the power of the symbolism of the condor is a product of the colonial process. I’ll leave that to the scholars.

[41] It is interesting to juxtapose the houses of the Rito with the houses of the common Incan citizen. While the Rito live in rather pristine environs, with houses clean and airy, the denizens living outside of Cuzco lived in slightly-less-than-desirable conditions:

“In stark contrast to the great buildings in the centre of Cuzco were the surrounding dwellings of the people constructed of dried adobe bricks, and in the highlands sometimes of stones. Hardly any vestiges are left of these small huts. Life inside them must have been more than spartan. They were always provided with a small entrance, but they had no windows and no vent for smoke. Almost the only furnishing was the blankets on which the inmates slept, but there were also niches in the wall in which some articles could be placed. Separate families lived in these huts, which they shared with a great number of the guinea pigs that were found in almost every peasant household.” [Emphasis mine.]

Katz, Friedrich. “The Civilizations of the Middle Andes.” The Ancient American Civilizations, p. 280. Castle Books, 2004.

We might look to the Muisca for at least the exterior architectural elements of Rito houses. Look at the replications that have been built of both the bohíos and the Temple of the Sun at Sugamuxi.

[42] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 131. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

“One of the Rito’s most useful qualities is that their bodies are completely covered in soft feathers which retain heat. That is particularly helpful since they dwell in a chilly climate, and it also enables them to fly high into altitudes where the cold is extreme. . . . The Rito have developed a thriving industry based on their feathers. Each individual’s feathers have unique coloration, and the Rito aesthetic draws on a wide palette as well. Their furniture and clothing are eye catching because of their bright, colorful patterns.”

[43] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 313. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

[44] Bernier, Hélène. “Birds of the Andes.” Metmuseum.org, June 2009, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bird/hd_bird.htm.

[45] Ibid.

[1] Sorry to my fellow continental Americans (especially the Brazilians among you — I know that you guys are particularly touchy about this), but there’s just no other good demonym for people from the United States . . .

[2] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 305. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

[3] Lin, Y. (1998). The Importance of Living, pp. 295-7. Quill, Willam Morrow.

[4] Three friends of winter | Chinese Art Gallery | China Online Museum. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2021, from http://www.chinaonlinemuseum.com/painting-three-friends-of-winter.php.

[5] Pine Painting | Chinese Art Gallery | China Online Museum. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2021, from http://www.chinaonlinemuseum.com/painting-pine.php.

[6] Wang, Y. (2018, March 1). The Moral Connotations of Pine and Cypress Trees. SSCP. Retrieved October 27, 2021, from http://www.csstoday.com/Item/5302.aspx.

Here’s another lovely article about pine trees, if the spirit so moves you.

[7] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 400. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

[8] Ibid., p. 125.

[9] Ibid., p. 131.

[10] Parkes, G., and Loughnane, A. (2018, December 4). Japanese Aesthetics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved October 27, 2021, from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/japanese-aesthetics/.

[11] Ibid.

[12] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 305. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

[13] Ibid., p. 307.

[14] There are always naysayers in the “groves of academe”, and some scholars enumerate other examples of “pristine” civilizations while still others deny the entire label as preposterous — how can any culture arise “independently”? What makes these societies in any way special? What makes this sort of development more precious than the societies of Neolithic peoples? But, to be honest, I think such scholars are throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Civilization is a very special thing: from decentralized, nomadic or hunter-gatherer tribal societies to those marked by agriculture and domestication, social stratification (and the specialization of labor), urban centralization, complex governance, and, most holy of holies, symbolic communication — such a jump demands some attention, if not respect. We can debate the relative merits of any of these aspects of civilization til the cows come home, but let us at least acknowledge that something special has taken place!

[15] Smithsonian Magazine. “First City in the New World?” Smithsonian.com, 1 Aug. 2002, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/first-city-in-the-new-world-66643778/.

[16] Betz, Eric. “Is Caral, Peru, the Oldest City in the Americas?” Discover Magazine, 2 Feb. 2021, https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/is-caral-peru-the-oldest-city-in-the-americas.

[17] Haas, Jonathan, and Winifred Creamer. “Crucible of Andean Civilization.” Current Anthropology, vol. 47, no. 5, 2006, pp. 745–775., https://doi.org/10.1086/506281.

[18] Moseley, M. E. (1975). The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization. Menlo Park: Cummings Publishing Company.

This theory has seemingly been refined and criticized for decades. See for a good overview: Beresford-Jones, D., Pullen, A., Chauca, G. et al. Refining the Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization: How Plant Fiber Technology Drove Social Complexity During the Preceramic Period. J Archaeol Method Theory 25, pp. 393–425 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-017-9341-3

[19] Mann, Charles C. “Unraveling Khipu's Secrets.” Science, vol. 309, no. 5737, 2005, pp. 1008–1009., https://doi.org/10.1126/science.309.5737.1008.

[20] Bushnell, Geoffrey H.S., and John V. Murra. “Andean Civilization.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/pre-Columbian-civilizations/Andean-civilization.

[21]“In contrast to the north coast of Peru, it never rains on the south coast. Accordingly textiles have endured here over thousands of years completely intact. In the years from 1925 to 1930 two large burial-grounds in the middle of the desert were excavated, Paracas Cavernas and Paracas Necropolis, in which a number of mummies were found. These had remained intact, thanks to the dryness of the climate, just like the woven fabrics in which they were wrapped. Additional fabrics and ceramic and precious metal objects were added to these woven textiles as burial offerings. While the textiles of Paracas Cavernas must be attributed to the pre-classic period and are in part coarsely woven, those of Paracas Necropolis are among the most beautiful and the richest found in America and perhaps in the whole world. Over a hundred shades of color were used and a great diversity of materials — cotton, wool and even human hair. The creators of these textiles are still unknown. Since the places where the burial enclosures are situated seem to have been uninhabited it is generally thought that corpses were transported there from far away. The similarity of some of the Paracas motifs to those of the Nazca valley a hundred kilometres further south indicates that the dead came from there.”

Katz, Friedrich. “The Civilizations of the Middle Andes.” The Ancient American Civilizations, pp. 105-6. Castle Books, 2004.

[22] On rectilinearity: “The technical requirements of the loom further restrict the designer: large curvilinear forms are generally impractical.”

On dyes: Colors used at Cavernas number only about 10 or 12 different shades, mostly browns, reds, yellow-oranges, blue-greens, and natural whites. In Necropolis and Nazca embroideries, we can see many more colors, around 190 in total.

Kubler, George. The Art and Architecture of Ancient America: the Mexican, Maya and Andean Peoples, p. 293. Penguin Books, 1962.

[23] Giovanetti, Marco, and Sofía Silva. “La Chakana En La Configuración Espacial De El Shincal De Quimivil (Catamarca).” Estudios Atacameños, vol. 66, 2020, pp. 213–235., https://doi.org/10.22199/issn.0718-1043-2020-0052.

[24] “The anthropomorphic or humanist bent of all Mesoamerican expression is carried by innumerable representations of the human figure. In the Andes a humanistic style appears only intermittently, as in Colombia and Ecuador, or on the north coast of Peru; elsewhere the human figure is subjected to complex deformations tending either to the emergence of monster-like combinations or to the dissolution of the human form in geometric abstractions. Throughout the Andes a dominant concern for technological control over the hostile environment is apparent.” [Emphasis mine.]

[25] “Inca.” The Dictionary of Art, vol. 15, pp. 163-4. Grove, 1996.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Seriously, get a look at some of this stuff (potentially not safe for work): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moche_culture#/media/File:Fellatiomoche.jpg

[28] “The Classic Tiahuanaco painted wares comprise handsome cups of concavely flaring profile, as well as libation bowls which are squat, wide versions of the cups. Both are painted in as many as five colours on a red slip with heavy black outlines surrounding the areas of local colour. The figures of pumas, human beings, and condors in profile are clearly delineated and easy to recognize.”

“The style of Tiahuanaco belongs to the Andean tradition of conventional signs ordered more by semantic needs than by mimetic relationships. It conveys information about ideas rather than pictures of things, and in this it resembles the art of Chavín, although major differences separate the two styles. Chavín objects are curvilinear and asymmetrical; those of Tiahuanaco are rectilinear and balanced. Chavín carving recalls woodworking and hammered metal; Tiahuanaco art evokes textile and basketry techniques.” [Emphasis mine.]

Kubler, George. The Art and Architecture of Ancient America: the Mexican, Maya and Andean Peoples, pp. 309-10. Penguin Books, 1962.

[29] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 129. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

[30] Ibid., p. 307.

[31] Werness, Hope B. The Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism in Art, pp. 294-5. Continuum, 2004.

[32] Geoglyphs can also be “positive”, created by an additive process such as an arrangement of stones or other materials to create images. Examples of this are the Cerne Abbas Giant near Dorset, England, which features chalk rubble, or the Great Serpent Mound in Ohio, USA, which is an effigy mound of piled earth.

[33] Werness, Hope B. The Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism in Art, p. 294. Continuum, 2004.

[34] Ibid., p. 295.

[35] Katz, Friedrich. “The Civilizations of the Middle Andes.” The Ancient American Civilizations, pp. 243-4. Castle Books, 2004.

Also: “A number of the motifs of this Gateway of the Sun, especially the geometric representations of puma and condor heads, recur with few variations over the entire Andean region.” (Ibid., p.109)

[36] Ibid., p. 109.

[37] Staller, John E.; Stross, Brian. Lightning in the Andes and Mesoamerica, Pre-Columbian, Colonial, and Contemporary Perspectives, p. 86. Oxford University Press, 2013.

[38] Werness, Hope B. The Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism in Art, p. 84. Continuum, 2004.

[39] Kubler, George. The Art and Architecture of Ancient America: the Mexican, Maya and Andean Peoples, p. 244. Penguin Books, 1962.

[40] Howard-Malverde, Rosaleen. “Between Text and Context in the Evocation of Culture.” Creating Context in Andean Cultures, Oxford University Press, New York, 1997, p. 16.

Note: The author here also goes on to state that perhaps the power of the symbolism of the condor is a product of the colonial process. I’ll leave that to the scholars.

[41] It is interesting to juxtapose the houses of the Rito with the houses of the common Incan citizen. While the Rito live in rather pristine environs, with houses clean and airy, the denizens living outside of Cuzco lived in slightly-less-than-desirable conditions:

“In stark contrast to the great buildings in the centre of Cuzco were the surrounding dwellings of the people constructed of dried adobe bricks, and in the highlands sometimes of stones. Hardly any vestiges are left of these small huts. Life inside them must have been more than spartan. They were always provided with a small entrance, but they had no windows and no vent for smoke. Almost the only furnishing was the blankets on which the inmates slept, but there were also niches in the wall in which some articles could be placed. Separate families lived in these huts, which they shared with a great number of the guinea pigs that were found in almost every peasant household.” [Emphasis mine.]

Katz, Friedrich. “The Civilizations of the Middle Andes.” The Ancient American Civilizations, p. 280. Castle Books, 2004.

We might look to the Muisca for at least the exterior architectural elements of Rito houses. Look at the replications that have been built of both the bohíos and the Temple of the Sun at Sugamuxi.

[42] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 131. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

“One of the Rito’s most useful qualities is that their bodies are completely covered in soft feathers which retain heat. That is particularly helpful since they dwell in a chilly climate, and it also enables them to fly high into altitudes where the cold is extreme. . . . The Rito have developed a thriving industry based on their feathers. Each individual’s feathers have unique coloration, and the Rito aesthetic draws on a wide palette as well. Their furniture and clothing are eye catching because of their bright, colorful patterns.”

[43] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 313. Dark Horse Books, 2018.

[44] Bernier, Hélène. “Birds of the Andes.” Metmuseum.org, June 2009, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bird/hd_bird.htm.

[45] Ibid.