The Fire Sanctuary

“Faron Woods . . . Eldin Volcano . . . and Lanayru Desert . . . A sacred flame is hidden somewhere in each of these lands. Seek them out, and purify your sword in their heat. Only after your blade has been tempered by these three fires will it be fully imbued with the great power for which you search.”

— Impa, Skyward Sword

As the spiritual representation of fire and strength, Din chose to house her Flame upon the very summit of Eldin Volcano, a peak of seismic power and roiling lava. From the religious history given to us in Ocarina of Time, we know that Din, with her strong flaming arms, cultivated the land and created the red earth. That Din, the deity most strongly represented by flame, strength, and earth, should be the primary Goddess of this volcanic region is therefore unsurprising, and fitting, given the thematic continuity and motifs of the series as a whole. Protecting this flame — the last, and likely, the strongest — is the sprawling complex known, in English, as the Fire Sanctuary, though the Japanese translation describes it simply as a Great Temple Shrine. Regardless of linguistic background, however, this structure is both vast and ancient, as well as a house and temple to fire and its worship.

Being the temple set at the greatest elevation in Skyward Sword, the entrances to this dungeon are few, and this sanctuary is the only such place upon the surface with a Bird Statue capable of reaching the sky. Link is able to gain access to the mountaintop through the volcanic summit, high above the rest of the mountainous area beyond. It should go without saying that the terrain of this location is one primarily of caverns, craters, and chambers of magma with small foot-paths weaving dangerously through the liquid rock. The nearby crater makes this area extremely hot, and thus the element water becomes the oppositional complement to this region, playing an integral part in entering the actual sanctuary.

— Impa, Skyward Sword

As the spiritual representation of fire and strength, Din chose to house her Flame upon the very summit of Eldin Volcano, a peak of seismic power and roiling lava. From the religious history given to us in Ocarina of Time, we know that Din, with her strong flaming arms, cultivated the land and created the red earth. That Din, the deity most strongly represented by flame, strength, and earth, should be the primary Goddess of this volcanic region is therefore unsurprising, and fitting, given the thematic continuity and motifs of the series as a whole. Protecting this flame — the last, and likely, the strongest — is the sprawling complex known, in English, as the Fire Sanctuary, though the Japanese translation describes it simply as a Great Temple Shrine. Regardless of linguistic background, however, this structure is both vast and ancient, as well as a house and temple to fire and its worship.

Being the temple set at the greatest elevation in Skyward Sword, the entrances to this dungeon are few, and this sanctuary is the only such place upon the surface with a Bird Statue capable of reaching the sky. Link is able to gain access to the mountaintop through the volcanic summit, high above the rest of the mountainous area beyond. It should go without saying that the terrain of this location is one primarily of caverns, craters, and chambers of magma with small foot-paths weaving dangerously through the liquid rock. The nearby crater makes this area extremely hot, and thus the element water becomes the oppositional complement to this region, playing an integral part in entering the actual sanctuary.

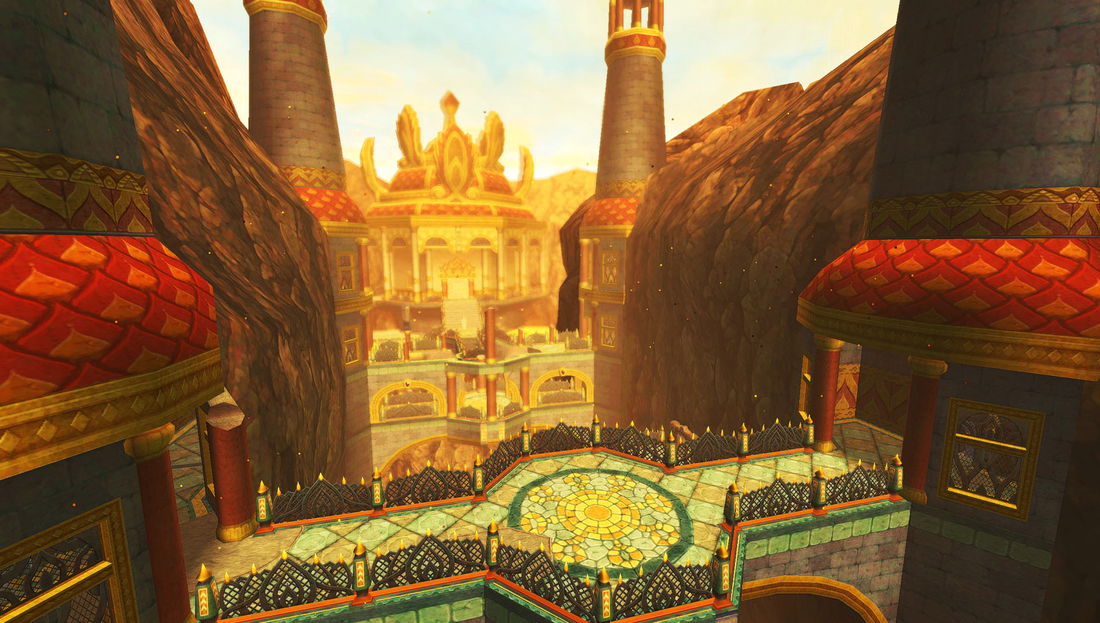

An initial series of gates serves to protect this complex, having been built into a natural cave system of brown stone. These gateways are considerably plainer and more subdued than those of its sister complex, the Earth Temple, which was fierce and unrelenting in its use of strong, vivid coloration. These three gates are barred by flames, and their protectors, a set of strange chimeric creatures resembling both bird and frog, demand a tribute of water before quelling their fire. These beings are ensconced in stone, with bulging eyes, and a pair of large, stone lips. Their bodies, held between webbed feet and tail, are marked with a symbol of water entering a vessel similar to a cauldron. In a way, these very creatures give, even without speaking, the clue to moving forward. The last, and greatest, of these statuary devices rests upon the main entrance to the temple. Across a narrow trefoil bridge of grey stone bricks, with an azure fence fancifully cast in the shape of orange-tipped rising flames, a large temple façade comes quickly into view with a massive, multi-tiered crown of red fire set between two tall towers. These thick towers are domed with two red roofs, which are further marked with four red leaves facing each direction, and topped with small finials (the spires that rest atop domes or towers) of metal. Immediately obvious are the few colorful patterns and materials set against the subtle grey-brown stone of the complex. The archways of blue tile in varying shades are surrounded by striped ribs of gold or yellow stone, and gold trim follows the upper and lower tracks of wall, as well as demarcating different levels of the structure in the form of simple stringcourses. The tiles upon the ground are of pastel teal blue and a yellow-orange, subtly complementing both of the stronger colors upon the wall. Initially, like the other gates, this one is sealed with fire, though the doorways to the flanking turrets are open, revealing a high space with open windows and delicate metalwork. These may have perhaps once served as guard posts, though this is not certain.

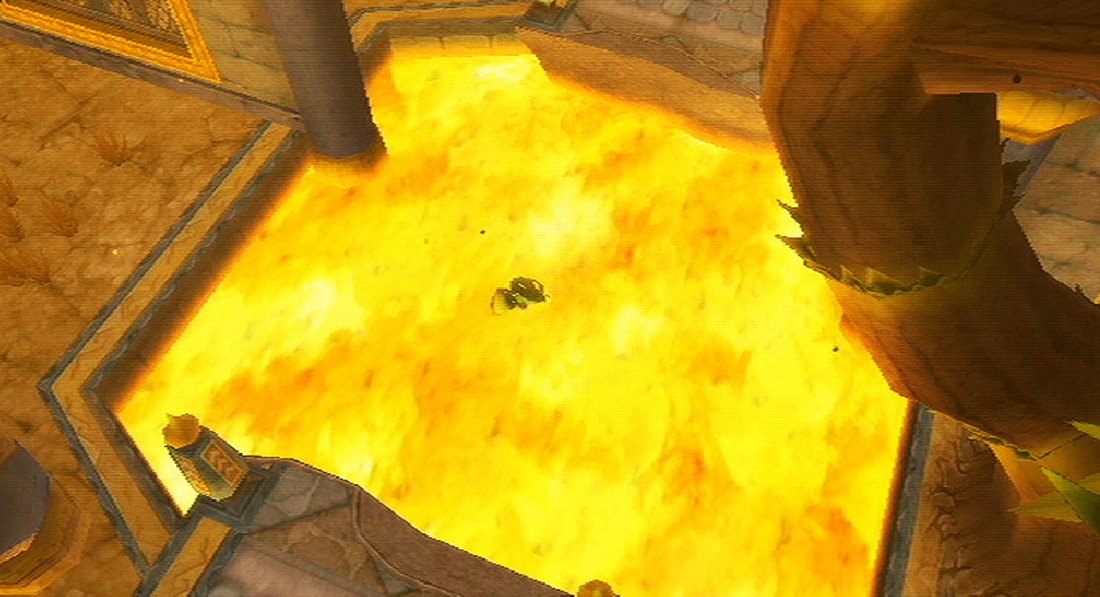

As with many other temples and dungeons throughout the surface world that have been built into caves, this one follows no logical plan in organization, likely having been built around the naturally-existing caverns and passages. Fascinatingly, the entire complex is bifurcated by an immense fissure, so that the temple itself is split into two halves that must be spanned by bridges, much like the two hemispheres of the brain are connected via the corpus callosum. The actual interior, then, lies behind these cliff walls. The floor, in many places, has been worn away, or perhaps never existed at all, and large tracts of wall and ceiling appear to be natural stone that was perhaps created by the lava flows that riddle this mountain summit.

As with many other temples and dungeons throughout the surface world that have been built into caves, this one follows no logical plan in organization, likely having been built around the naturally-existing caverns and passages. Fascinatingly, the entire complex is bifurcated by an immense fissure, so that the temple itself is split into two halves that must be spanned by bridges, much like the two hemispheres of the brain are connected via the corpus callosum. The actual interior, then, lies behind these cliff walls. The floor, in many places, has been worn away, or perhaps never existed at all, and large tracts of wall and ceiling appear to be natural stone that was perhaps created by the lava flows that riddle this mountain summit.

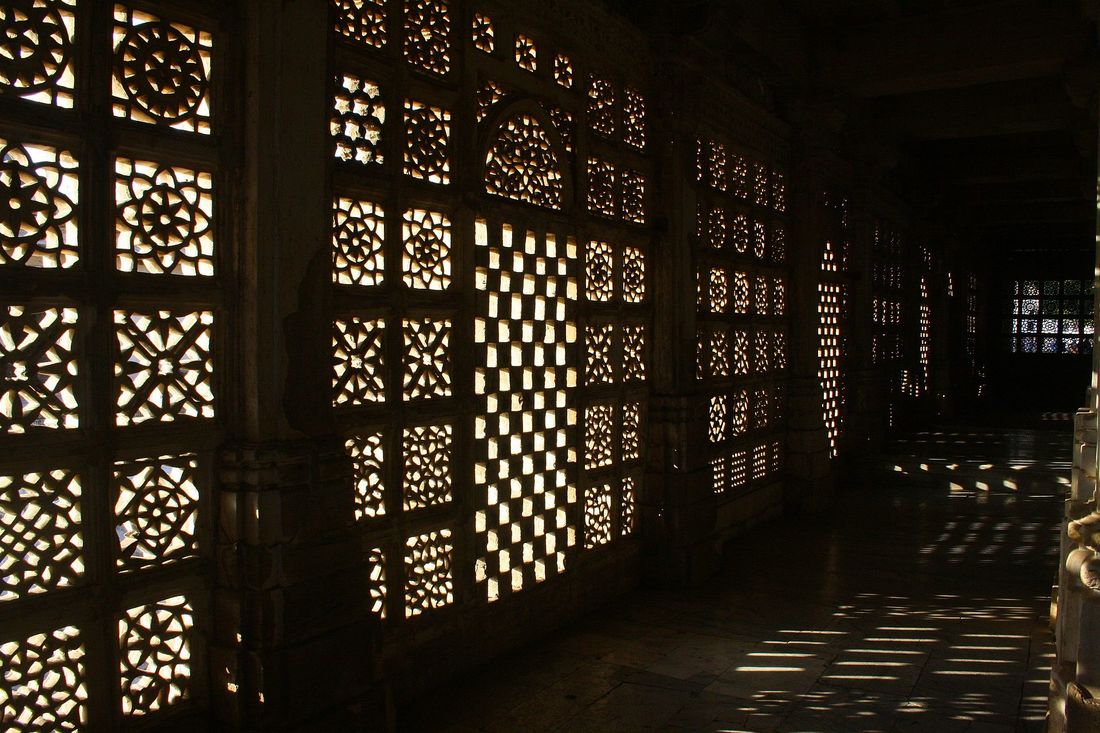

Not uncommon, a descending staircase leads into the sanctuary, and, as in the Earth Temple, the air is almost visible due to the intense heat refraction and dull particles floating on streams of air. The ground in this initial chamber is a plain dirt floor, somehow still marked with dried, yet growing, grass. Brick walls of blue and cobalt stone hold metal screens, called jaali in Hindi, which are demarcated with golden trim; these are both a decorative and defensive feature, and, as these are primarily geometric in design, these likely take their provenance from Indo-Islamic temples. Now is as good a time as any to discuss a hugely important aspect of both Islam and the architecture over which it exerted near-absolute influence. This concept is called Aniconism (meaning against icons), and, to an extent, it is also found in sects of Christianity, Buddhism, and Judaism. Most educated persons know that, within Islam, it is forbidden to depict the Prophet Muhammad or the Islamic deity, Allah; similarly, this proscription leads downward in the great chain of beings, from god to man, and from man to animal. Indeed, through the hadith (the purported collections of the teachings and injunctions of the Prophet Muhammad), we know that the depiction of any sentient being in any form of art is manifestly forbidden. [1] The reason for this is that any act of sub-creation (as Tolkien would have called a god-made artist making art of his or her own) is still an act of creation, which is the domain of god. God created both man and world, and it is therefore reasoned that god alone should have full control over the creation of life — even in art. Thus, Islamic architecture and art have been dominated by elaborate and ornate geometric patterning, calligraphy, and the well-known arabesque — abstract plant life which finds synthesis with geometric designs. In this sanctuary, consequently, there are very few representations of any sentient life (save those features which hail from other real-world architectural schools, or from in-game schools; after all, this temple does house composite architecture of many styles), and most decorative elements are simple, geometric patterns which pay respect to the author of the universe.

Jaali at Sarkhej Roza, India: Chaitra.sharad - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21670389

Architecturally, this building unquestionably lifts its features from the pages of real-world architecture, as we have briefly discussed, paying subtle homage to the grand traditions of the past. And, like nearly every creation within the series, it is not a pure representation of any one convention or school, but a composite of many ages, peoples, and styles. While there are assuredly countless motifs drawn from architectural schools the world over present in all of these temples and fortresses, the Fire Sanctuary draws primarily from Islamic architecture (Moorish architecture from the Iberian Peninsula and Northern Africa, as well as the colorful sub-cultural schools of Persia and Mughal India), as well as East and Southeast Asian traditions from China to Thailand.

In stark contrast to the non-representative aspects of Islamic art within this temple setting are the owl statues that flank the initial crumbling staircase. Created from stone and rock, these owls are robed and crowned, with cream-colored breast feathers, blue wings and brow, with two multifaceted rubies for eyes. Their foreheads are further marked with a diamond emblem, reflective of the gold crowns encrusted with emeralds above. And it should be noted that these statues are in pairs. Though not rare in architecture, owls are not commonly-featured animals — especially within temples. In a fascinating article on Shang Dynasty culture from pre-dynastic China, author Wang Tao examines Shang pottery and metalworking in an attempt to uncover the mysterious representation — both abstract and literal — of the owl in Shang works. [2] While there are many theories circulating around this issue, with many different scholars in many different camps, it has been posited by some that this bird deity could have represented the sun, which would tie into the nature of this sanctuary almost perfectly. And like the actual intellectual battle over the meaning of the owl in Shang art, the origins of these statues within the Fire Sanctuary are also shrouded in mystery. Whether they are protector spirits, or represent true sight or wisdom, is unknown. The only thing we do know is the prevalence of bird iconology within Goddess Architecture within this game; perhaps, then, these owls are indirect homages to the goddess Hylia and her sacred birds.

Within this area are several other points of interest that will appear throughout the temple: simple columns of stone — both red and blue — are ubiquitous, and are capped with bulbous golden bases and capitals; small balusters, and their metal railings, carry chevron designs and are dominated by small bulbs reminiscent of the onion domes present in Mughal architecture; finally, the most obvious aspect of embellishment here is the flame motif that ranges from abstract to concrete. Along walls, atop fences and posts, and upon roof-tiles, ruby-red and gold flames rise upward, peaking, and giving rise to yet more flames, reflecting the self-renewing nature of fire in the presence of life.

Shortly after this opening room, we reach the true nexus of the temple, which is the vast chasm that vivisects this structure. High above a river of churning lava, several thin bridges span the crevasse, in the distance, high, piercing towers break the sky, and, at the end of the fissure, a larger temple can be seen. These bridges, which are two-level structures composed primarily of arches and supported by columns, form octagons in the center — directly above the fire below. Within these octagonal protrusions, set against the diagonally-running tiles, are very abstract symbols of the sun, with curvilinear rays of light stretching out in eight directions. These flames are reflected in the metal railings of these bridges, as well as upon the ceiling tiles of the minaret-like towers that house doors leading into the temple. The architecture of this chasm is incredibly cohesive, as the picture above clearly demonstrates, from the tapering minarets to the crowned sanctuary at the far end.

Perhaps the most interesting, even mysterious, aspect of this temple is the underground passage system currently inhabited by the Mogma — a burrowing species of treasure hunters seeking riches and adventure. These subterranean tunnel-ways are small, cramped spaces which occasionally house storage chests, and strange mechanisms that are necessary for the opening of gateways above the surface. If these devices were originally a part of the creation of this place, then it hints at one of two things: either the Mogma (or their ancient predecessors) were involved in the creation of this protective sanctuary, or the people that inhabited this region were somehow skilled in burrowing, and were thus able to build such complexities into their defensive systems. Because the Mogma give no hint at why these spaces exist, or how these mechanisms are related to the gateways above, the matter is unsolvable, and we must leave it at that.

Shortly after this opening room, we reach the true nexus of the temple, which is the vast chasm that vivisects this structure. High above a river of churning lava, several thin bridges span the crevasse, in the distance, high, piercing towers break the sky, and, at the end of the fissure, a larger temple can be seen. These bridges, which are two-level structures composed primarily of arches and supported by columns, form octagons in the center — directly above the fire below. Within these octagonal protrusions, set against the diagonally-running tiles, are very abstract symbols of the sun, with curvilinear rays of light stretching out in eight directions. These flames are reflected in the metal railings of these bridges, as well as upon the ceiling tiles of the minaret-like towers that house doors leading into the temple. The architecture of this chasm is incredibly cohesive, as the picture above clearly demonstrates, from the tapering minarets to the crowned sanctuary at the far end.

Perhaps the most interesting, even mysterious, aspect of this temple is the underground passage system currently inhabited by the Mogma — a burrowing species of treasure hunters seeking riches and adventure. These subterranean tunnel-ways are small, cramped spaces which occasionally house storage chests, and strange mechanisms that are necessary for the opening of gateways above the surface. If these devices were originally a part of the creation of this place, then it hints at one of two things: either the Mogma (or their ancient predecessors) were involved in the creation of this protective sanctuary, or the people that inhabited this region were somehow skilled in burrowing, and were thus able to build such complexities into their defensive systems. Because the Mogma give no hint at why these spaces exist, or how these mechanisms are related to the gateways above, the matter is unsolvable, and we must leave it at that.

The true sanctuary, resting at the utmost end of the chasm outside, is a truly interesting structure, both inside and out. The ogive arches of the moors, with their alternating colors, are obvious, and the ceiling, with its several tiers and large decorative leaves, is a shorter reflection of the minarets in the canyon, as well as the crown of flames above the first gateway into the dungeon. The room which houses the Boss Key is particularly interesting, and not just because the Boss Key is referred to as the King’s Treasure (after all, who is this king? Did he rule this land, or is this just a moniker given to the key by the treasure-seeking Mogma?); within this room, birds take prominence in the designs, dominating the walls in relief, and resting upon the floor as statues. These statues differ greatly from the owl statues first seen, in that they have their wings outstretched (like the more familiar Bird Statues), and are crowned with fire, like phoenixes from myth. Both of these elements will play a role in the grand culmination of this temple, which is nearly a replica of the sanctum sanctorum of Skyview Temple — creating a lovely final echo of design from the first temple of this game to the last.

As with the final chamber of Skyview Temple, this room is utterly spectacular. Beginning with the dome above, this dome is of simple stone blocks, like the rest of the temple, in the form of an octagon with bronze ribbing encasing the room. Metal-gilded windows fill the room with orange light, which is ambiguously reflected in the flame designs near the large amulet in the center of the dome. Each corner of this octagonal room has a column, and this column takes the shape of a robust bird: a feathered body and jeweled eyes support their fluted capitals, which attend all three layers of wall, terminating in the metal ribbing of the dome. Yet, two of the birds — those framing the way to the Goddess Flame — are far, far more elegant. Perhaps of a different species of bird, these two creatures are red, white, and gold, and have elongated necks, which curve elegantly and face one another; graceful plumage, neck bracers, and crowns of gold all help to accentuate their importance relative to the other columnar birds. And, as in Skyview, the outstretched wings of these birds encircle the room, forming support for the ogival arcade and entablature above. The entablature, which has historically been home to telling stories through architecture, is no different within this temple, and houses rich illustrations that are as strange as they are beautiful.

As with the final chamber of Skyview Temple, this room is utterly spectacular. Beginning with the dome above, this dome is of simple stone blocks, like the rest of the temple, in the form of an octagon with bronze ribbing encasing the room. Metal-gilded windows fill the room with orange light, which is ambiguously reflected in the flame designs near the large amulet in the center of the dome. Each corner of this octagonal room has a column, and this column takes the shape of a robust bird: a feathered body and jeweled eyes support their fluted capitals, which attend all three layers of wall, terminating in the metal ribbing of the dome. Yet, two of the birds — those framing the way to the Goddess Flame — are far, far more elegant. Perhaps of a different species of bird, these two creatures are red, white, and gold, and have elongated necks, which curve elegantly and face one another; graceful plumage, neck bracers, and crowns of gold all help to accentuate their importance relative to the other columnar birds. And, as in Skyview, the outstretched wings of these birds encircle the room, forming support for the ogival arcade and entablature above. The entablature, which has historically been home to telling stories through architecture, is no different within this temple, and houses rich illustrations that are as strange as they are beautiful.

Resting between the arcade above, and relief-section below (whose reliefs are of birds from the King’s Chamber, as well as the Sunburst design upon the floor in this room and upon the bridges over the chasm), is a tripartite series of panels that encircles the entire room. The panels upon six of the eight walls are in three segments, and each vertical segment depicts several pyramids — three smaller, one larger — and people bowing in prostration. Upon the far wall, between the ornate bird statues discussed above, are the three most striking panels, for they tell far more than the others. Housed within rays of golden light and designs in cloud and wind, these three panels depict the Gates of Time, as well as the abstract image of the goddess found within all her architecture. On the leftmost panel, we see a Gate of Time against a landscape of brown and tan. This undoubtedly represents the Gate of Time previously found in the Temple of Time in Lanayru Province — marked by pyramids, two high towers, cacti, and worshippers. Above the Gate is a full Hylian symbol of Triforce and Wings, exactly like the ancient Temple of Time hidden at the edge of the desert. To the far right, this scene is echoed almost perfectly in shades of green, except that the building has become the Sealed Temple, with its striking roof and four cardinal turrets, and is protected by a deep forest represented by four tall trees. These two Gates act as pathways to the goddess, having been an integral part of her designs throughout the ages, and this temple enshrines both their power and beauty, as well as their prominent place in the iconology of goddess worship upon the surface — a worship that once encompassed all the land.

Works Cited:

[1] “Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History." Figural Representation in Islamic Art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, n.d. Web. 15 July 2015. <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/figs/hd_figs.htm>.

[2] Wang, Tao. "The Owl in Early Chinese Art: Meaning and Representation on Sotheby’s Blog.” The Owl in Early Chinese Art: Meaning and Representation. Sotheby’s, n.d. Web. 15 July 2015. <http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/2014/sakamoto-n09124/sakamoto-goro/2014/02/the-owl-in-early-chi.html>.

[1] “Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History." Figural Representation in Islamic Art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, n.d. Web. 15 July 2015. <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/figs/hd_figs.htm>.

[2] Wang, Tao. "The Owl in Early Chinese Art: Meaning and Representation on Sotheby’s Blog.” The Owl in Early Chinese Art: Meaning and Representation. Sotheby’s, n.d. Web. 15 July 2015. <http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/2014/sakamoto-n09124/sakamoto-goro/2014/02/the-owl-in-early-chi.html>.