The Fire Temple

"It is something that grows over time . . . a true friendship. A feeling in the heart that becomes even stronger over time . . . The passion of friendship will soon blossom into a righteous power and through it, you will know which way to go . . . This song is dedicated to the power of the heart . . . Listen to the Bolero of Fire . . . ."

— Sheik, Ocarina of Time

— Sheik, Ocarina of Time

Picture Credit: http://qlockwork.deviantart.com/

Certainly, fire evokes a great many concepts and emotions. It is both a symbol of home and comfort, and of wanton and indifferent destruction. It is hearth, and it is conflagration. The Gorons revere fire, and their temple is a house of this element.

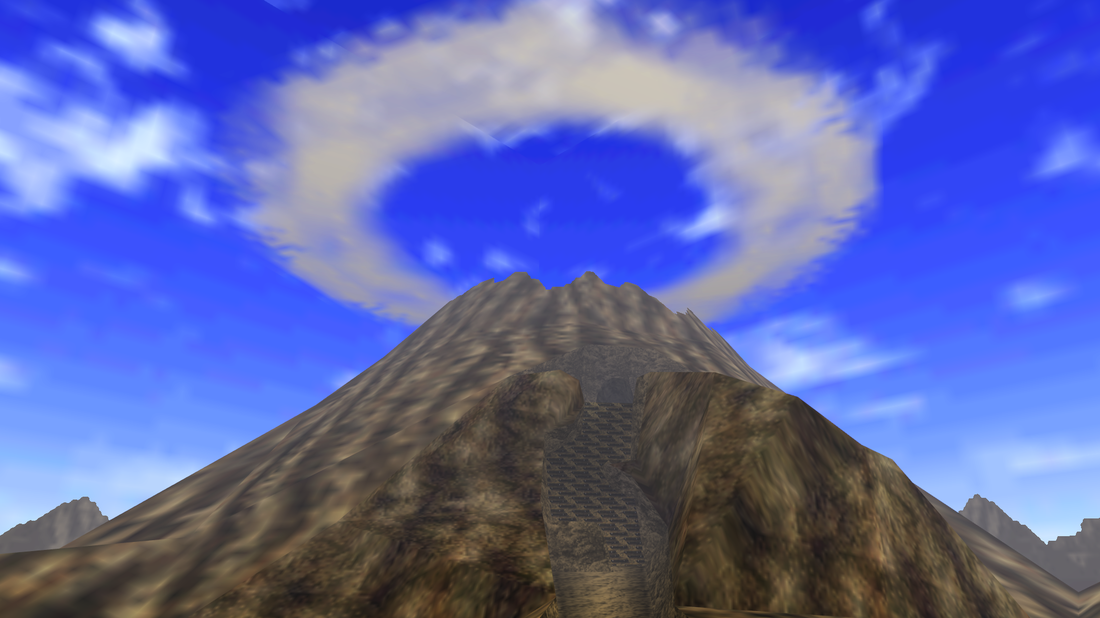

The volcano itself is a symbol equally important to the Gorons, directly reflecting the state of the civilization of those living on and within the mountain. It is known that when the clouds ringing the summit are normal, then Death Mountain is at peace. As with many societies living in particular places, they pour themselves into the land. The terrain is anthropomorphized: it takes on moods, feelings, and characteristics; it metamorphoses into spirits and gods; and it is worshipped and revered.

The volcano itself is a symbol equally important to the Gorons, directly reflecting the state of the civilization of those living on and within the mountain. It is known that when the clouds ringing the summit are normal, then Death Mountain is at peace. As with many societies living in particular places, they pour themselves into the land. The terrain is anthropomorphized: it takes on moods, feelings, and characteristics; it metamorphoses into spirits and gods; and it is worshipped and revered.

There are several places of importance on Death Mountain Trail, and each is distinct. The main dwelling place of the Gorons is Goron City, high above Dodongo’s Cavern (their chief mine), and this is the principal gateway to Death Mountain Crater, which ultimately ends in the heart of the mountain: the Fire Temple.

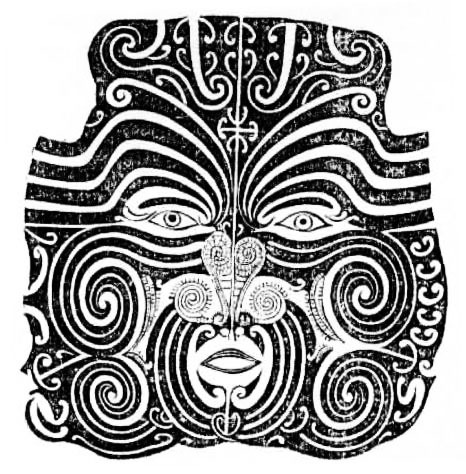

Goron City is an interesting nexus of society, having entrances to both the nearby Death Mountain Crater as well as the more distant Lost Woods. It is a multilevel edifice, seemingly created using a top-to-bottom approach, with the most important rooms being on the lowest level. Everything is delved from the living rock, and upon the walls are paintings — representational but not realistic — of the Gorons, the Dodongos, and of elemental fire. These markings are, at least in part, a narrative of Goron history; it is the telling of a story, and it is a constant, edifying reminder of what has passed. In the center, held aloft by three ropes, is a platform upon which the Goron Ruby, the Spiritual Stone of Fire, was once displayed. The passageways and staircases within the city are numerous, and there are many strange, unexplained rooms. The use of multitudinous small flags demarcate doors, passages, and are also found in Darunia’s chambers. They bear the symbol of the Gorons, and of the Triforce and Royal Family. Outside Darunia's room, there is a massive earthenware vase, three-sided, with each face portraying a different expression: anger, contentment, and joy. The living quarters of the Goron Chief are also unique for their wall decorations. The walls, floor, and ceiling are all of rough stone, but here we first witness the abstract, tribal art of the Gorons. The wall paintings here resemble eyes, large and unblinking, highly abstracted, and surrounded with coiling, labyrinthine lines, circles, and angular projections more than slightly redolent of the tā moko body markings of the Māori. They appear as disconcerting masks, and frame the highly-stylized statue of an aged Goron, behind which rests the portal into Death Mountain Crater.

Goron City is an interesting nexus of society, having entrances to both the nearby Death Mountain Crater as well as the more distant Lost Woods. It is a multilevel edifice, seemingly created using a top-to-bottom approach, with the most important rooms being on the lowest level. Everything is delved from the living rock, and upon the walls are paintings — representational but not realistic — of the Gorons, the Dodongos, and of elemental fire. These markings are, at least in part, a narrative of Goron history; it is the telling of a story, and it is a constant, edifying reminder of what has passed. In the center, held aloft by three ropes, is a platform upon which the Goron Ruby, the Spiritual Stone of Fire, was once displayed. The passageways and staircases within the city are numerous, and there are many strange, unexplained rooms. The use of multitudinous small flags demarcate doors, passages, and are also found in Darunia’s chambers. They bear the symbol of the Gorons, and of the Triforce and Royal Family. Outside Darunia's room, there is a massive earthenware vase, three-sided, with each face portraying a different expression: anger, contentment, and joy. The living quarters of the Goron Chief are also unique for their wall decorations. The walls, floor, and ceiling are all of rough stone, but here we first witness the abstract, tribal art of the Gorons. The wall paintings here resemble eyes, large and unblinking, highly abstracted, and surrounded with coiling, labyrinthine lines, circles, and angular projections more than slightly redolent of the tā moko body markings of the Māori. They appear as disconcerting masks, and frame the highly-stylized statue of an aged Goron, behind which rests the portal into Death Mountain Crater.

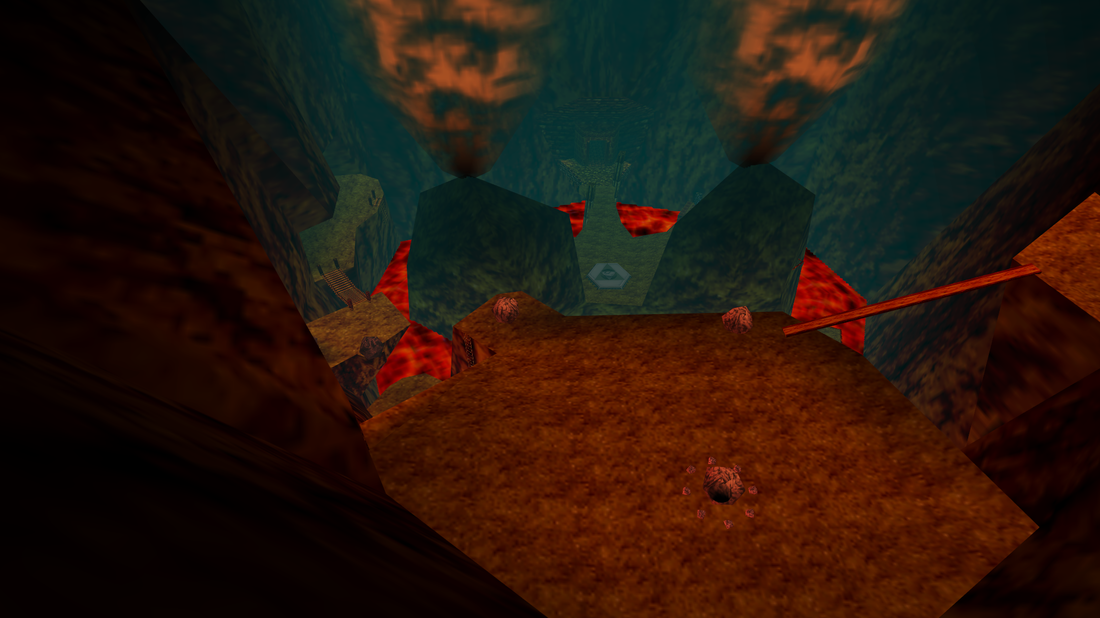

After passing through the crater, full of broken outcroppings of rock, crumbling columns protruding from the lava, and the unbearable heat, the temple begins with a descent. Under the gaze of immense stony faces, the only way in is a downward plunge.

As the temple is located within an active volcano, there are limits as to the dimensions of the structure, spatially. Roughly speaking, the construct is conical in nature, following the natural upthrust and tapering of the mountain. The bottom floor is the most sprawling, and contains the most rooms; gradually, the space of the upper levels diminishes appropriately. There exist two central chambers within the temple that are relatively round, and that lessen in size as one ascends through the complex. Because of their duality, their positioning, and the way that they taper to a point, it has been conjectured that these rooms exist on the interior of Spectacle Rock, the two smaller peaks within Death Mountain Crater.

As the temple is located within an active volcano, there are limits as to the dimensions of the structure, spatially. Roughly speaking, the construct is conical in nature, following the natural upthrust and tapering of the mountain. The bottom floor is the most sprawling, and contains the most rooms; gradually, the space of the upper levels diminishes appropriately. There exist two central chambers within the temple that are relatively round, and that lessen in size as one ascends through the complex. Because of their duality, their positioning, and the way that they taper to a point, it has been conjectured that these rooms exist on the interior of Spectacle Rock, the two smaller peaks within Death Mountain Crater.

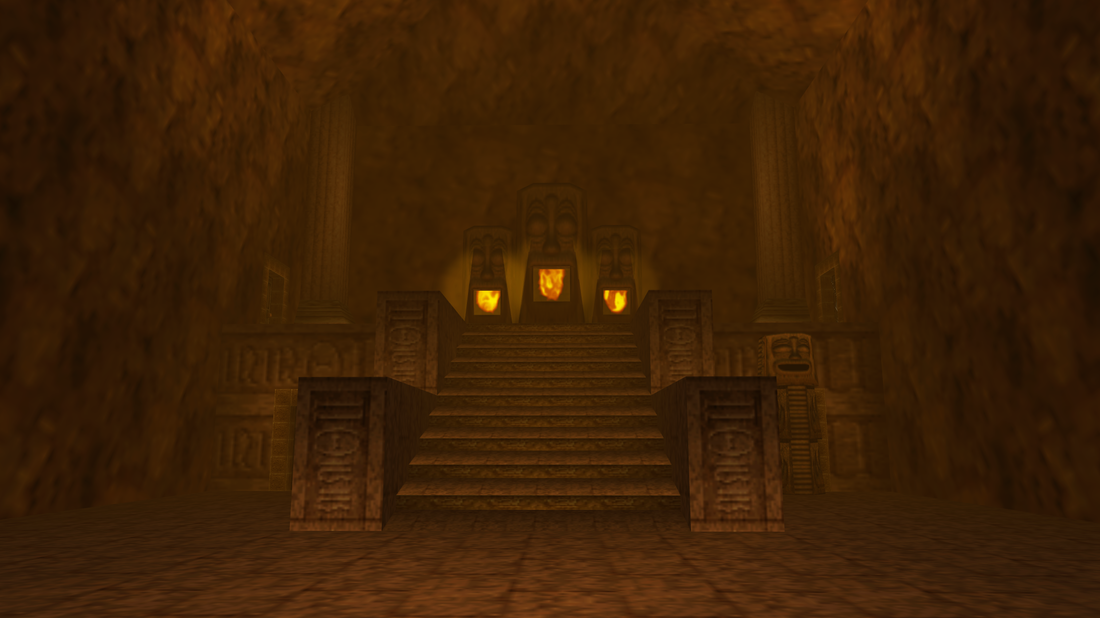

Upon entering, Link is greeted with fiery-mouthed statues that seem to mirror real-world tikis (also of Māori culture) or the totemic, statuesque carvings seen in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The large staircase in the antechamber is ornate, with strange, unknown markings which are also found upon various other walls throughout the building. Other architectural curiosities of note are small panels, bearing the insignia of a burning flame, and larger panels bearing the simple, yet unexplained, representation of an open-mouthed visage. Most of the temple is constructed of simple brown stone, without any form of adornment. Sandy-colored bricks are another oft-seen material, and the floor and columns (fluted, with dark grey bases), resemble a light rose in coloration. In certain rooms, especially in the central chambers, small niches appear, as would hold the images of Arhats or Bodhisattvas in certain temples of the East. However, in this temple they remain black windows, and are unadorned. Many doors seem to be constructed of a heavy metal, with bars across the windows. These, along with the existence of many cages within the complex, the walls of fire, myriad booby traps, and fake doors, give the edifice the dual appearance of being both a holy place and a prison. One must wonder at the reasons behind such extravagant traps and snares, and ponder whether they are protecting something, holding something back, or if this is simply the standard for a temple of Goron design.

The musical theme of this temple is but a shadow of what it should have been. Originally featuring a culturally-rich (pseudo-) Islamic chanting, it was removed after the initial release, and we are therefore left with a considerably more prosaic version. [1] Like the ascent of a mountain, the music slowly builds, from the low howling of wind to an ancient-sounding percussion set. A vaguely-tambourine-sounding instrument begins, echoed by a curious stringed instrument, and then the well-known Goronian drums follow; lastly, simple bells ring out in groups of four, completing the theme. Even without the chanting, the impression is as primal as the fire it seeks to emulate. Such earnest simplicity, done passionately, accentuates the extremely elemental nature of this temple: fire was among the initial essentials of humanity, and perhaps this theme seeks to hearken back to more primordial epochs, calling forth both the fundamental and the elemental.

In comparison with the other temples that have been discussed, this one seems largely unremarkable — it lacks the architectural maturity and foresight of the Forest Temple, and the thoughtfulness and complexity of the Water Temple. Yet, perhaps that is the point. It is more basal than the others for the simple reason that it seeks, above all other things, to glorify the element for which it was constructed. The simplicity and unadorned nature of this structure brings fire — its colors, essence, and emotions — to the forefront of the mind, displaying it in a piercingly brutal fashion.

In comparison with the other temples that have been discussed, this one seems largely unremarkable — it lacks the architectural maturity and foresight of the Forest Temple, and the thoughtfulness and complexity of the Water Temple. Yet, perhaps that is the point. It is more basal than the others for the simple reason that it seeks, above all other things, to glorify the element for which it was constructed. The simplicity and unadorned nature of this structure brings fire — its colors, essence, and emotions — to the forefront of the mind, displaying it in a piercingly brutal fashion.

Addendum (Changes in the 3DS Version):

The updated version adds splendid paneling and wall-based artwork. This temple now properly reflects the tribalism and subterranean nature of the Gorons as a people.

The columns are labyrinthine, literally carrying the motif of a maze upon them. On several other walls do we find this design, echoing the nebulous underground passages within these structures. The stringcourses within this complex are also of this nature, carrying a horizontal labyrinth around entire rooms.

The structure is ablaze in orange, red, and yellow. The colors have become prodigiously elemental so as to adequately do the concept of fire justice. The wall decorations reflect the importance of the inferno. There are several different panel styles to be found within the Fire Temple. They are, in no particular order: tribal face decorations, masks, a flower of flame with a coiled dragon inside, stylized fire, and, in the room with the Megaton Hammer, four coiled dragons wreathed in flame. Most obvious are the adornments on the way to Volvagia’s chamber, the dragon itself being the incarnate spirit of Death Mountain. [2] The door itself is red and orange, bearing a symmetrical flame within a labyrinth, all upon a field of brown. It is ringed with an industrial-looking black metal, perhaps in an attempt to contain the evil within. Flanking the portal are two giant-order panels. They are magnificent, with highly abstracted fire upon them. The floor tiles upon the platform in the last chamber appear to be of writhing dragons.

Such paneling adds unbelievable richness and a sense of architectural splendor previously not experienced. The spirits of fire, revered for their power, are now paid homage to respectfully and with an air of grandeur.

The updated version adds splendid paneling and wall-based artwork. This temple now properly reflects the tribalism and subterranean nature of the Gorons as a people.

The columns are labyrinthine, literally carrying the motif of a maze upon them. On several other walls do we find this design, echoing the nebulous underground passages within these structures. The stringcourses within this complex are also of this nature, carrying a horizontal labyrinth around entire rooms.

The structure is ablaze in orange, red, and yellow. The colors have become prodigiously elemental so as to adequately do the concept of fire justice. The wall decorations reflect the importance of the inferno. There are several different panel styles to be found within the Fire Temple. They are, in no particular order: tribal face decorations, masks, a flower of flame with a coiled dragon inside, stylized fire, and, in the room with the Megaton Hammer, four coiled dragons wreathed in flame. Most obvious are the adornments on the way to Volvagia’s chamber, the dragon itself being the incarnate spirit of Death Mountain. [2] The door itself is red and orange, bearing a symmetrical flame within a labyrinth, all upon a field of brown. It is ringed with an industrial-looking black metal, perhaps in an attempt to contain the evil within. Flanking the portal are two giant-order panels. They are magnificent, with highly abstracted fire upon them. The floor tiles upon the platform in the last chamber appear to be of writhing dragons.

Such paneling adds unbelievable richness and a sense of architectural splendor previously not experienced. The spirits of fire, revered for their power, are now paid homage to respectfully and with an air of grandeur.

Notes and Works Cited:

[1] "There are three main releases of Ocarina of Time. There is version 1.0, 1.1., and 1.2 (the Game Cube and Virtual Console releases are modified versions of version 1.2). Only versions 1.0 and 1.1 have the original fire temple music; every version after that has a revised version."

Hagopian, Mases. “The Legend of Music #03: The Fire Temple Controversy.” Zelda Dungeon, 7 Apr. 2012, www.zeldadungeon.net/the-legend-of-music-03-the-fire-temple-controversy/.

[2] “Historical Records.” The Legend of Zelda — Encyclopedia, by Keaton C. White and Tanaka Shinʼichirō, Dark Horse Comics, 2018, p. 22.

[1] "There are three main releases of Ocarina of Time. There is version 1.0, 1.1., and 1.2 (the Game Cube and Virtual Console releases are modified versions of version 1.2). Only versions 1.0 and 1.1 have the original fire temple music; every version after that has a revised version."

Hagopian, Mases. “The Legend of Music #03: The Fire Temple Controversy.” Zelda Dungeon, 7 Apr. 2012, www.zeldadungeon.net/the-legend-of-music-03-the-fire-temple-controversy/.

[2] “Historical Records.” The Legend of Zelda — Encyclopedia, by Keaton C. White and Tanaka Shinʼichirō, Dark Horse Comics, 2018, p. 22.