The Twilight Realm and the Palace of Twilight

“My god had only one wish . . . to merge shadow and light . . . and make darkness!”

— Zant, Twilight Princess

— Zant, Twilight Princess

Upon first entering the Twilight Realm, it is anything but the place of serene beauty described by Midna. In the first commentary concerning this game, I gave a selection of quotes pertaining to the hour of twilight which sought to highlight its meaning within the sphere of human existence — particularly the moods that it is capable of evoking. For many, this hour is one of depth and splendor, and it is a beauty that is made all the more exquisite for its tenuous existence hovering between the light of day and the darkness of night. Darkness is unsettling for most, and this is, and has been, reflected in art, history, and culture the whole world over since mankind first came into its own sapience. Quite naturally, because daylight both grants and represents clear vision, warmth, and safety, the ineluctable blotting out of light from the world must have been both beautiful and worrisome to behold for early humanity. At this hour, shadow and light come together in a delicate, preordained dance, until one inexorably yields to the other, cloaking the world in umbral stillness.

The Mirror of Twilight itself recognizes this relationship, tracing its brilliant white lines through ebon rock and the sky itself

For some reason, nearly all villains prefer darkness to light. Zant, under his god, Ganondorf, seeks to cast out all pure light from the world, creating a land of perpetual shadow. This process began in the Twilight Realm with the theft of the Sols. The Sols, small orbs which function as the light sources of this realm, were taken from the Sol Shrine at the heart of the plaza in front of the Palace of Twilight. Stolen by Zant and hidden away, their disappearance led to the blacking out of the light and the transformation of the Twili into Shadow Beasts. [1] As the tale recounts, Zant, feeling both unwanted and useless, pleaded for power into a listening void. When an entity ultimately answered his cry, Zant usurped the throne using his newfound power, displacing a magic-less, imp-like Midna into a world not her own, leaving her embittered and alone. And this is where Twilight Princess really comes into its own, showing a masterful development of themes. Link and Midna, representing the light and shadow of their respective realms, collide in the periphery of the machinations of Zant, and initially they mix as do oil and water. Most inhabitants of the Kingdom of Hyrule show very mixed emotions that generally border on fear when the coming darkness is brought up, and, initially, both Midna and Link misunderstand the needs, nature, and normalcy of their separate planes of existence. Throughout the story, these two counter-locations and counter-identities play off of one another, their cultures and essences flowing from Midna into Link and from Link into Midna. Eventually, the two characters find abiding love and respect for one another. Their two worlds, which at first seemed irreconcilably different, are ultimately shown to be opposing sides of the same coin. The Hero and his Companion are but microcosms of these larger themes at play within this tale, and the most imperative message of this work is that of conciliation and understanding.

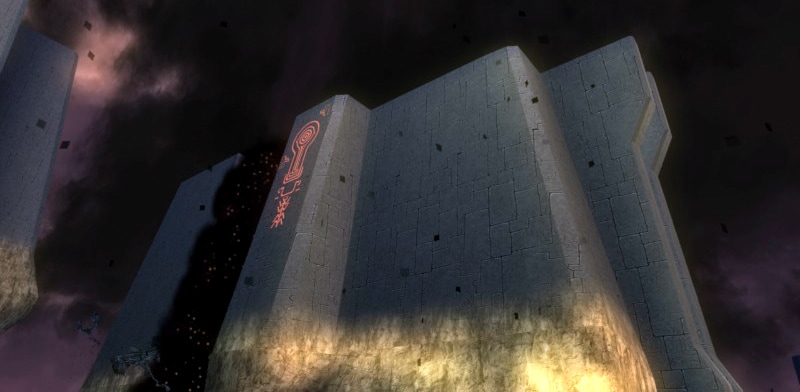

Though Midna admits that she was, at the outset, merely using Link to re-assemble the Mirror of Twilight, she finally divulges that she came to care for him and his land just as much as she cares for her own. So, once all of the Mirror Shards are accounted for, Midna and Link set forth from high atop the Arbiter’s Grounds and travel through the Mirror of Twilight to the home of the Twili. They are greeted by a tenebrous sky of pale yellows and faint purples. Black clouds coalesce and fade in the distance, obscuring dark islands and concealing unknown structures. And, as is characteristic of this location, strange pixelated motes float overhead and underfoot, as though this realm seeks to be a simulacrum of its medium.

Peaceful is not quite the adjective to describe this place, for while it is peaceful it is also unsettling. The backdrop to the musical setting is the rising dissonance of a music box, to which the sickly melody struggles to adhere, its synthetic bells and falling tones creating a feeling of bottomless instability and slight madness. All music pertaining to the Twilight within this game is meant to portray, at some level, an uncontrollable disquiet bordering on schizophrenia. This is among the gentlest of its incarnations, while that of the palace is more somber and rigid, and that of dispelling the Twilight from Hyrule is nothing if not deeply disturbing. There is good reason for this, whether or not it was originally intended. We hear and interpret this music, first and foremost, through Link — an inhabitant of the world of light. This space, which lacks the familiarity of sun and horizon, is not made to be pleasing or welcoming to a human traveler. It is a matter of perspective. We cannot separate ourselves from our cultural biases, and in creating this region of shadow an equally uncomfortable musical atmosphere was necessary. Were the main character of the Twili, and we able to understand such a people, the setting would undoubtedly be changed dramatically, simply due to perception. But we are human travelers in an odd fictional universe, and we are rightfully disturbed.

Peaceful is not quite the adjective to describe this place, for while it is peaceful it is also unsettling. The backdrop to the musical setting is the rising dissonance of a music box, to which the sickly melody struggles to adhere, its synthetic bells and falling tones creating a feeling of bottomless instability and slight madness. All music pertaining to the Twilight within this game is meant to portray, at some level, an uncontrollable disquiet bordering on schizophrenia. This is among the gentlest of its incarnations, while that of the palace is more somber and rigid, and that of dispelling the Twilight from Hyrule is nothing if not deeply disturbing. There is good reason for this, whether or not it was originally intended. We hear and interpret this music, first and foremost, through Link — an inhabitant of the world of light. This space, which lacks the familiarity of sun and horizon, is not made to be pleasing or welcoming to a human traveler. It is a matter of perspective. We cannot separate ourselves from our cultural biases, and in creating this region of shadow an equally uncomfortable musical atmosphere was necessary. Were the main character of the Twili, and we able to understand such a people, the setting would undoubtedly be changed dramatically, simply due to perception. But we are human travelers in an odd fictional universe, and we are rightfully disturbed.

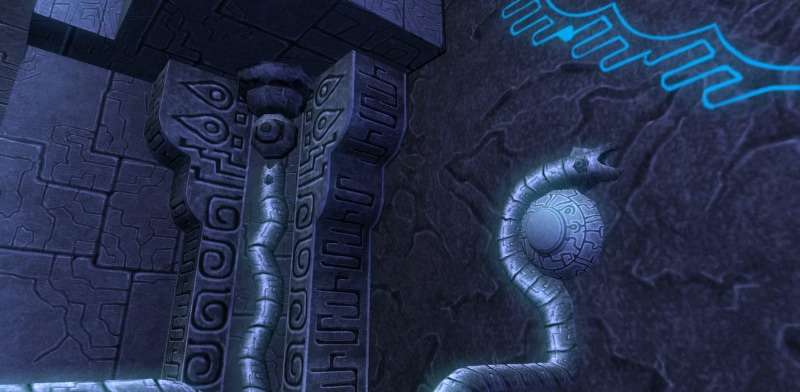

The architecture of the Twili is utterly unique. Their buildings rise from incongruous brown stone, and appear as worn monoliths standing solitary against the strange sky and shifting clouds; these are austere structures with slanting walls and fierce angularity, perhaps reflecting Twili conceptions of beauty, royalty, or power — we cannot be sure. Upon the ashen grey walls are neon patterns of red and blue running circuit-like in tight forms like veins in a living organism. They seem to pulse with life, as if they, through their eccentric channels and shapes, provide life and energy to the buildings themselves. Huge columns of ruby-infused black smoke flow through conduits at the top of each of these three structures and pour endlessly into the empty sky below. To human eyes, all is faded, grim, and bleak.

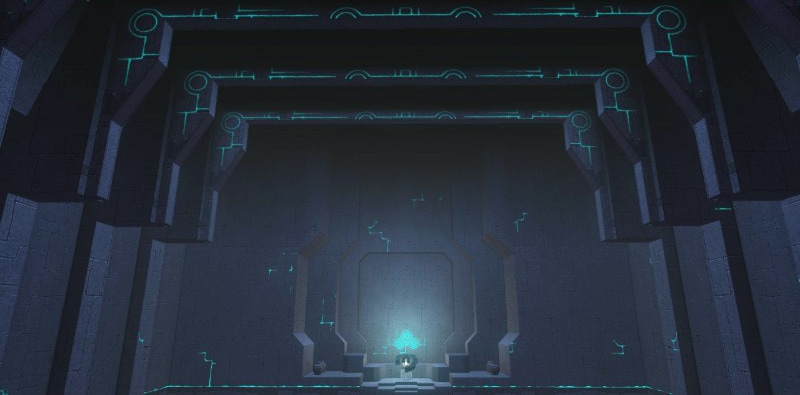

Essentially, the interior is much the same as the exterior in terms of materials, layout, and overall architectural style. The veins of light are more ubiquitous here, running myriad, thin courses through the grey stone, almost like mortar between individual bricks. Black orbs rest in metal encasements, and are activated when struck; these control seemingly-impossible floating platforms, whose shape and solidity are defined solely by light. These provide access to nearly all the doors within the Palace of Twilight, as normal sets of stairs are rare. In many of the rooms, small platforms simply jut out of walls, with no form of access provided, and, given the height of some of the chambers, these would be impossible to reach for most visitors. Sources of illumination within the palace are few, and therefore the majority of the complex is slightly obscured. The same ruby-filled black haze can be found hugging the floors and walls tightly in certain areas, and it has the curious ability to alter Link’s appearance from his light-world form into the form of the Sacred Beast.

Please note two things: first, the masonry of the walls is either oddly-fitted stones done without mortar, or a set of larger bricks superficially carved into strange sizes and pieces using different tools; second, pay attention to the moving platforms, and how they seem to be created only from lines of energy. This same energy can be seen pulsing in the walls and upon the pillars in this room.

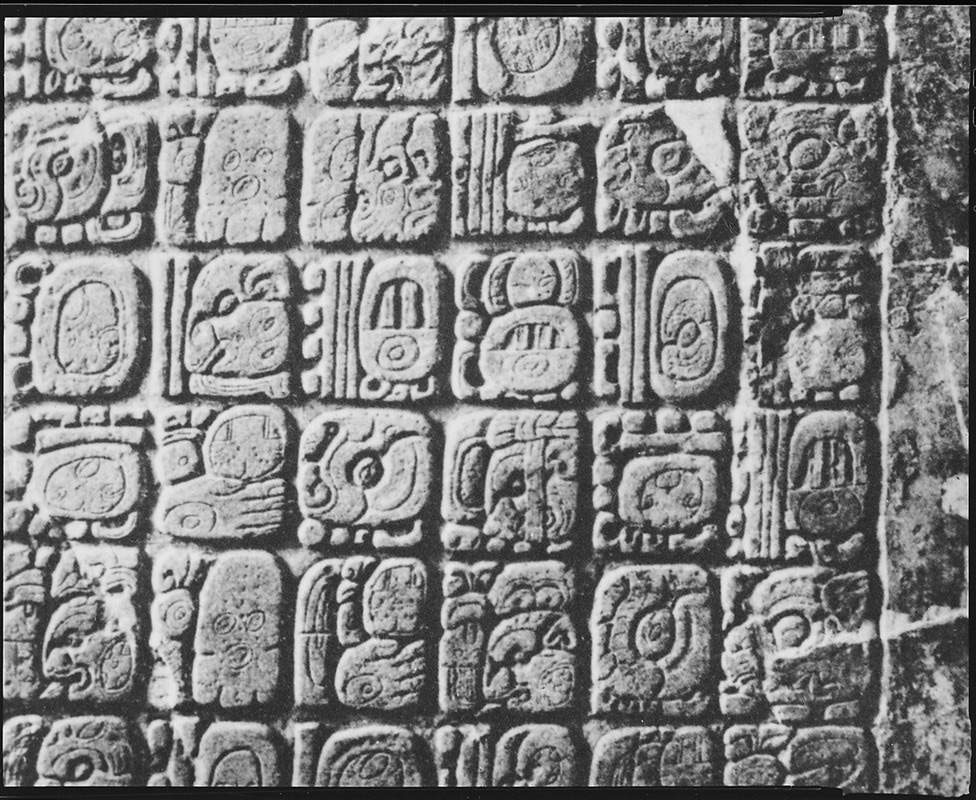

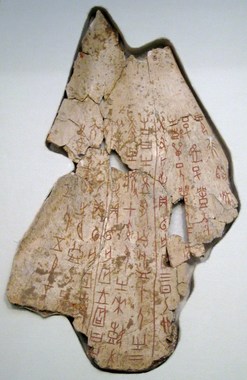

The one culture we know of to have inspired the design of the Twilight Realm and all its inhabitants is that of ancient China — specifically, the Shang Dynasty, which lasted from c. 1600 to 1046 BCE. [2] [3] Insofar as I can tell, this inspiration seems to bear itself out in three primary places: character design, symbols, and architectural embellishments. I will focus my attention on the latter two categories, beginning with the curious symbols found upon and within Twili structures. While many of the designs show great resemblance to computer circuitry, as has been stated, other symbols, specifically those found within the throne room and upon the freestanding pillars in the picture directly above, seem much more mysterious, and much more ancient. What is stranger still is that the pillars seem to bear two distinct forms of script or symbol: the upper two designs are enclosed, rougher, and seem to a fixed external structure, while the bottom designs seem to be made up of many smaller components, which focus on semi-connected dots, lines, and simpler geometric shapes. The upper designs, though we have little idea what they could mean, seem to be loosely derivative of ancient Maya script, a set of logograms used for many centuries by some peoples of Mesoamerica. The lower symbols — which may be script or simply decoration — seem taken from several cultural artifacts from Shang Dynasty China; these markings bear passing resemblance to Oracle Bone Script and to the decorative elements found upon many pieces of Shang bronze-ware, examples of which are shown below.

|

A set of Mayan glyphs from the Temple of the Cross in Palenque, Mexico. While these glyphs are certainly more representational than those symbols found in the Palace of Twilight, there is still some resemblance in their organization and quadratic design.

Above right: A sample of Oracle Bone Writing from the reign of King Wu Ding of the late Shang dynasty. [4]

Middle right: A ding from the late Shang dynasty. [5] Here we can clearly see the inspiration for the design elements found within the Twilight Realm — the curvilinear, yet thick, lines, the circuit-like tracings, the eyes, and the animalistic forms. The image on this device, and on many other ceremonial bronze pieces from early Chinese dynasties, is called taotie, and its meaning is, as yet, uncertain, though there are many related theories. [6] The taotie symbol is representative of one of the four demons of ancient China, taotie meaning "gluttonous beast". These masks are characteristically zoomorphic, which, "may be divided, through the nose ridge at the center, into profile views of two one-legged beasts . . . confronting each other. A ground pattern of squared spirals, the "thunder pattern" (lei-wen), often serves as a design filler between and around the larger features of the design." [7] This motif has no decided-upon meaning, and it has been hypothesized that it may be, ". . . totemic, protective, or an abstracted, symbolic representation of the forces of nature." [8] Bottom right: The ceramic pot to the direct right, from the Palace of Twilight, shows these same "squared spirals" and protruding, segmented lines, in a color that is almost the same as the Shang bronze-ware above. Truly, these Shang Dynasty design elements were folded into the very fabric of the Twilight Realm. |

The final chamber is, by any measure, the grandest, reflecting the very height of Twili art and architecture. The walls fold in, out, and upward at various angles, and stones of various greys make up the walls, pillars, and stairs. Behind the throne is an enormous design in vivid blue, appearing technological and natural all at once — both wire-work and birds' wings. The dark-stone pillars are engraved with designs similar to the bronze-ware embellishments above, and, in the corners, two snakes coil up the pilasters, while two of their kin form the balustrades on either side of the staircase, like the Nāga present in Lake Hylia's sacred spring. And while all of these decorative elements speak to the cultural milieu of the Shang Dynasty, the throne seems almost ripped from the pages of history itself. With its harsh, blocky spiraling on each side and its antennae-esque protrusions, and given its complex trace curls and spirals, it looks very much like the bronze bo bell shown below.

Perhaps the most iconic aspect of this dungeon is the guardian hand shown above. Its appearance is a direct copy of the actual hands of the Shadow Beasts, with the elongated pointer and pinky fingers and dominant thumb. These protectors remain still until their treasure (the Sol) is disturbed, after which they promptly begin a ceaseless hunt until either they or Link are victorious.

As the Twilight Realm serves as the penultimate stage of this play, so to speak, it sets an atmosphere of rising tension which leads to climax and a heart-rending denouement. Through the Mirror of Twilight, we are given a fleeting glimpse into the life of Midna and the Twili at a very critical point in the shaping of their future. It really is invaluable, as well as touching. The dialogue between Princess and Usurper reflects some of the deeper issues at play within all governance — those of lost power, of banishment, and of the Mandate of Heaven: those chosen by the gods to rule. Beneath the immediate surface of this world are powerful, ancient forces continually surfacing and sinking, never finding harmony. Would Zant have triumphed, twilight would have spread fear and hopeless shadow throughout the planes. His defeat spelled the end for this bleak perception, allowing Midna to return this world to the state of serene repose so beautiful to her.

Alfred T. Bricher's Twilight in the Wilderness — image in the public domain

Notes and Works Cited:

[1] The Sols, in addition to being sources of power, are also capable of repelling dark magic. As concerns the Twili, who were changed to Shadow Beasts, they are a rather sullen people, rarely speaking but to each other, and each bears a pattern on the chest which represents their clan in the Twili Hierarchy. The Twili were originally a magically-gifted people of Hyrule, but after they sought to establish dominion over the Sacred Realm, they were banished to the Twilight Realm by the four Light Spirits of the Goddesses. They, the so-called Interlopers, had their magic siphoned from them and sealed away in powerful artifacts called Fused Shadows, eventually becoming the Twili, a group forever kept from Hyrule's light. Their system of government seems to be founded on force, as the strongest magic users among them tend to end up as king or queen.

“Historical Records: Other Lands & Realms.” The Legend of Zelda — Encyclopedia, by Keaton C. White and Tanaka Shinʼichirō, Dark Horse Comics, 2018, pp. 30-31.

[2] Tanner, Aria, Hisashi Kotobuki, Heidi Plechl, Michael Gombos, Patrick Thorpe, and Cardner Clark. "Encoded in Illustrations." The Legend of Zelda: Art & Artifacts. Milwaukee, OR: Dark Horse, 2017. 420. Print.

Yusuke Nakano said, specifically, "At the time, when I was thinking up a design for the character [Midna], I wanted to search through some image sources not typically used in games. So I searched in various places and eventually ended up looking at bronze artifacts from the Shang dynasty. I felt like I could feel life within them, and their shape and form were really interesting."

[3] Ibid.

Yusuke Nakano also stated, when he was designing Zant: "At one point, I was drawing shapes that made me think of Southeast Asia. I made that shape into the head, added hands and feet, and when I started to clean up the character, there was Zant." It is not certain which Southeast Asian cultures in particular inspired this character.

[4] User: BabelStone. Shang Dynasty Inscribed Scapula. Digital image. Wikimedia Commons. N.p., 22 Aug. 2011. Web.

[5] User: Mountain. Liu Ding. Digital image. Wikimedia Commons. N.p., 27 Feb. 2006. Web. 21 Mar. 2017.

[6] Hogarth, Brian, and Carla Brenner. "Bronze Age China." The Golden Age of Chinese Archaeology: Celebrated Discoveries from the People's Republic of China. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1999. 146-47. Print.

[7] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Taotie." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 05 Apr. 2002. Web. 21 Mar. 2017.

[8] Ibid.

[1] The Sols, in addition to being sources of power, are also capable of repelling dark magic. As concerns the Twili, who were changed to Shadow Beasts, they are a rather sullen people, rarely speaking but to each other, and each bears a pattern on the chest which represents their clan in the Twili Hierarchy. The Twili were originally a magically-gifted people of Hyrule, but after they sought to establish dominion over the Sacred Realm, they were banished to the Twilight Realm by the four Light Spirits of the Goddesses. They, the so-called Interlopers, had their magic siphoned from them and sealed away in powerful artifacts called Fused Shadows, eventually becoming the Twili, a group forever kept from Hyrule's light. Their system of government seems to be founded on force, as the strongest magic users among them tend to end up as king or queen.

“Historical Records: Other Lands & Realms.” The Legend of Zelda — Encyclopedia, by Keaton C. White and Tanaka Shinʼichirō, Dark Horse Comics, 2018, pp. 30-31.

[2] Tanner, Aria, Hisashi Kotobuki, Heidi Plechl, Michael Gombos, Patrick Thorpe, and Cardner Clark. "Encoded in Illustrations." The Legend of Zelda: Art & Artifacts. Milwaukee, OR: Dark Horse, 2017. 420. Print.

Yusuke Nakano said, specifically, "At the time, when I was thinking up a design for the character [Midna], I wanted to search through some image sources not typically used in games. So I searched in various places and eventually ended up looking at bronze artifacts from the Shang dynasty. I felt like I could feel life within them, and their shape and form were really interesting."

[3] Ibid.

Yusuke Nakano also stated, when he was designing Zant: "At one point, I was drawing shapes that made me think of Southeast Asia. I made that shape into the head, added hands and feet, and when I started to clean up the character, there was Zant." It is not certain which Southeast Asian cultures in particular inspired this character.

[4] User: BabelStone. Shang Dynasty Inscribed Scapula. Digital image. Wikimedia Commons. N.p., 22 Aug. 2011. Web.

[5] User: Mountain. Liu Ding. Digital image. Wikimedia Commons. N.p., 27 Feb. 2006. Web. 21 Mar. 2017.

[6] Hogarth, Brian, and Carla Brenner. "Bronze Age China." The Golden Age of Chinese Archaeology: Celebrated Discoveries from the People's Republic of China. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1999. 146-47. Print.

[7] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Taotie." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 05 Apr. 2002. Web. 21 Mar. 2017.

[8] Ibid.