Goron City and Death Mountain

"Gorons gulp down rock by the mouthful, relax in bubbling lava, and don't see any value in gems. You didn't hear this from me, but . . . that's just plain crazy."

— Savelle, Breath of the Wild

“I love to invent peoples, tribes, racial origins . . . I return from my tribes. As of today, I am the adoptive son of fifteen tribes, no more, no less. And they in turn are my adopted tribes, for I love each of them more than if I had been born into it.”

— Deleuze & Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

“Medieval writers will wrestle with the idea that stone might itself be a kind of organism, might possess something like animam viventem, a creaturely soul.”

— Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman

— Savelle, Breath of the Wild

“I love to invent peoples, tribes, racial origins . . . I return from my tribes. As of today, I am the adoptive son of fifteen tribes, no more, no less. And they in turn are my adopted tribes, for I love each of them more than if I had been born into it.”

— Deleuze & Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

“Medieval writers will wrestle with the idea that stone might itself be a kind of organism, might possess something like animam viventem, a creaturely soul.”

— Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman

Author’s Note:

This article is a combined effort between my friend Clara and me, without whom I probably wouldn’t have written an article on Goron City, and especially not one this long. I have never been overly happy to write about Gorons, as I find them rather hokey and bumbling at the best of times (not to mention architecturally-uninspired); but as Clara finds them endlessly fascinating, as well as a lens through which to view some of the more arcane fields of human study, I figured she was the one to lead me to a greater understanding — and dare I say appreciation? — of everything Goron. It has proved quite the strange adventure for the both of us, and though we may disagree at times or even express contradictory opinions (sometimes in the same paragraph), I hope you enjoy all that the Goron can teach you. Just remember: the riddle is the message.

Secondary Author’s Note:

As a long-time fan of this website, I am honored and grateful for the opportunity to share our findings with its readers. When I pitched my idea for this article, Talbot was justifiably skeptical. On the face of it, there is not much to expatiate on; Gorons are straightforward creatures. Breath of the Wild’s complexity, however, allows us to give them a second look and attempt to move beyond a more narrow understanding of art and architecture. To this end, I embraced the Deleuzian turn in Game Studies. While Deleuze can feel disorienting at times, relaxing and following the flow is the best way to read his philosophy. And while I was at it, I jumped at the chance to air some interpretations and speculations. I hope I have done my part towards giving a voice to the untalkative Goron.

Caveat Lector:

As you read, you will find a series of “interludes” written by Clara; there are three in total, and each highlights a certain aspect of Goron culture, ethology, or being. To me, these are flights of fancy launched by the whimsical mind in a period of conjecture and wonder; they are the daydreams spawned by a mind playing with its object. They are curious things, and I have interspersed them throughout the text where I felt appropriate, in her unadulterated words as much as possible. Take them in stride, and carry them with you as you read.

This article is a combined effort between my friend Clara and me, without whom I probably wouldn’t have written an article on Goron City, and especially not one this long. I have never been overly happy to write about Gorons, as I find them rather hokey and bumbling at the best of times (not to mention architecturally-uninspired); but as Clara finds them endlessly fascinating, as well as a lens through which to view some of the more arcane fields of human study, I figured she was the one to lead me to a greater understanding — and dare I say appreciation? — of everything Goron. It has proved quite the strange adventure for the both of us, and though we may disagree at times or even express contradictory opinions (sometimes in the same paragraph), I hope you enjoy all that the Goron can teach you. Just remember: the riddle is the message.

Secondary Author’s Note:

As a long-time fan of this website, I am honored and grateful for the opportunity to share our findings with its readers. When I pitched my idea for this article, Talbot was justifiably skeptical. On the face of it, there is not much to expatiate on; Gorons are straightforward creatures. Breath of the Wild’s complexity, however, allows us to give them a second look and attempt to move beyond a more narrow understanding of art and architecture. To this end, I embraced the Deleuzian turn in Game Studies. While Deleuze can feel disorienting at times, relaxing and following the flow is the best way to read his philosophy. And while I was at it, I jumped at the chance to air some interpretations and speculations. I hope I have done my part towards giving a voice to the untalkative Goron.

Caveat Lector:

As you read, you will find a series of “interludes” written by Clara; there are three in total, and each highlights a certain aspect of Goron culture, ethology, or being. To me, these are flights of fancy launched by the whimsical mind in a period of conjecture and wonder; they are the daydreams spawned by a mind playing with its object. They are curious things, and I have interspersed them throughout the text where I felt appropriate, in her unadulterated words as much as possible. Take them in stride, and carry them with you as you read.

Once again, Link finds himself at the crossroads near the mouth of the Zora River. The southern path has led him to the lush world of the Zora, culminating in the taming of Vah Ruta and his reunion with the shade of Princess Mipha. He has quelled the floodwaters and provided a balm to wounds between longstanding allies — setting the region on the path to both physical and emotional healing. But his journey is far from ending, and much remains to be done before he is able to face Ganon at the heart of the kingdom. And so this time turning left, he sets his sights on the vast cone of fire in the distance: Death Mountain.

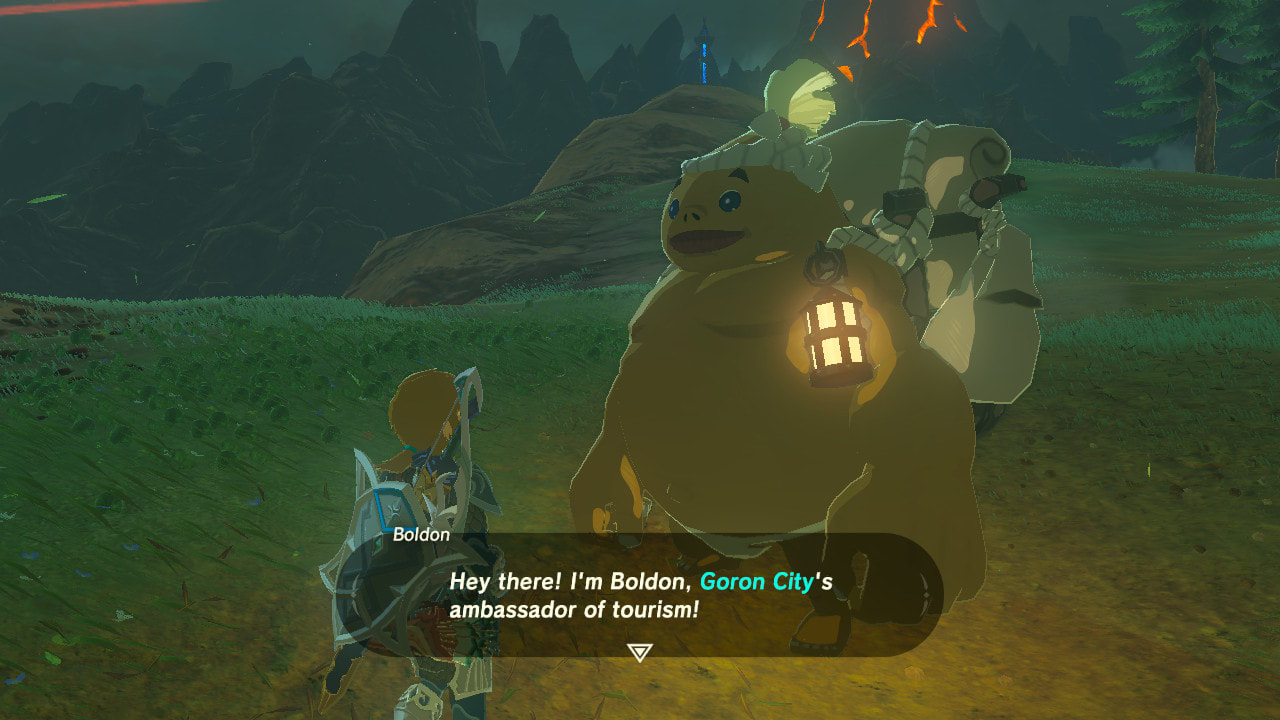

Not far along this pathway, he encounters Boldon, Goron traveler and Ambassador of Tourism for Goron City, who recommends heartily that Link visit his people, though he is also quick to point out that visitors there are in greater danger due to the rampage of Vah Rudania at the volcano’s summit. And as Link comes soon to find out, Goron City, while not existentially threatened, is suffering from an ailing economy and dangers on the road. Now is no time for tourism in Hyrule, and the dangers treading the land make even journeys of necessity cautious things. Though there were no long-term consequences for the stability of this area of Hyrule after the Great Calamity, and for the most part the Gorons were spared any disruption, there is still evidence of the Calamity along the road: the carapaces of destroyed Guardians lie scattered across the feet of Death Mountain, alongside burned wagons and desecrated campsites of days gone by. But Gorons are hardy folk, given their tenacious and roving natures, and at the time of Breath of the Wild, they are just as widespread as Hylians across Hyrule. [1] So Gorons are not strangers to Link. But they are strange. And if Link is anything like me, at some point along his journey into Goron lands, he likely puts to himself a question akin to this: just what is a Goron? No other entity is as strange in all of Hyrule — no other being so anomalous. The other races have their being through evolution traced from the animal kingdom, carrying all the genetically-familiar baggage expected: kinship with other species extant or extinct, sexual dimorphism, cycles of birth and death. But not so the Goron. The Goron seems to transcend nature, yet is at the same time completely immanent.

Not far along this pathway, he encounters Boldon, Goron traveler and Ambassador of Tourism for Goron City, who recommends heartily that Link visit his people, though he is also quick to point out that visitors there are in greater danger due to the rampage of Vah Rudania at the volcano’s summit. And as Link comes soon to find out, Goron City, while not existentially threatened, is suffering from an ailing economy and dangers on the road. Now is no time for tourism in Hyrule, and the dangers treading the land make even journeys of necessity cautious things. Though there were no long-term consequences for the stability of this area of Hyrule after the Great Calamity, and for the most part the Gorons were spared any disruption, there is still evidence of the Calamity along the road: the carapaces of destroyed Guardians lie scattered across the feet of Death Mountain, alongside burned wagons and desecrated campsites of days gone by. But Gorons are hardy folk, given their tenacious and roving natures, and at the time of Breath of the Wild, they are just as widespread as Hylians across Hyrule. [1] So Gorons are not strangers to Link. But they are strange. And if Link is anything like me, at some point along his journey into Goron lands, he likely puts to himself a question akin to this: just what is a Goron? No other entity is as strange in all of Hyrule — no other being so anomalous. The other races have their being through evolution traced from the animal kingdom, carrying all the genetically-familiar baggage expected: kinship with other species extant or extinct, sexual dimorphism, cycles of birth and death. But not so the Goron. The Goron seems to transcend nature, yet is at the same time completely immanent.

Interlude: Mythology and Schizoanalysis

“What is it to have a rock nature? This question puts our mind in a petromorphic state.” [2]

If the multiplicity of races sharing the world of The Legend of Zelda didn’t exist, the Hylian imagination would have needed to invent them. They are lines of flight from a State machine that is perpetually in the process of reconstituting itself. Mythically predicated on a recursive, ontologizing struggle against chaos, it places a high value on overcoding and reterritorialization as translatio imperii. Through all their vicissitudes in time and space, Castle, Temple, and Lost Woods impose meaning on the land, distribute religious and political power, and superpose the bright shadow of the Sacred Realm on the finite world, tracing a path only Hylia’s chosen can walk. Yet the same Hero that acts as cultural ambassador to enlist the support of the races under the aegis of a single royal house can do so only by traversing all the planes and affirming all becomings: inviting the player in turn to become-scrub, become-fish, become-woman, become-rock, transformations most solidly expressed in games like Majora’s Mask, wherein Link becomes envoy to the disparate races of Hyrule by becoming them.

Among the races capable of forming assemblages with the Hylian majority in creative becomings, Gorons are the most alien and uncanny, and the most powerful and exhilarating. The full body of the Earth is the Goron desiring-machine and production-machine, hearkening “. . . back to a time before the man-nature dichotomy, before all the coordinates based on this fundamental dichotomy have been laid down. He does not live nature as nature, but as a process of production. There is no such thing as either man or nature now, only a process that produces the one within the other and couples the machines together.” [3] Gorons are both producers and product, caught in a utopian cycle that satisfies all their needs with the least possible number of variables; as such, even as they remain embedded in their territoriality, they represent the absolute limit that is a constant opportunity and invitation to experiment for all Hyrulean races: “the unequal, the coarse, the rough, the cutting edge of deterritorialization.” [4] For anyone, then, that desires to be something other than they are — to experience newness through breaking down old ways of being, recreating themselves in the process — the Goron stands as testament to the possibility of transformation.

And there are many other frameworks for understanding the peculiar allure Gorons hold for us. The lithic hybridization of our imagination brings us back to primeval fancies of autochthonous birth, at-one-ness with the substance of the landscape, and erotic involvement with the living rock. The question almost begs itself: just how do Gorons reproduce? The absence of female Gorons must not lead us to postulate an estrangement from the feminine. Foreclosed from association with the opposite gender, the sons of stone may be even closer to the archetypal feminine in its petric, chthonic aspect: the strong- and red-armed mother Din who dances and stomps tectonic plates into chains of mountains: petra genitrix, matrix mundi. We see no shortage of world myth in which humanity springs forth from the earth “. . . engendered by a chthonian Great Goddess . . . the Armenians thought the earth was the ‘maternal womb, whence men came forth.’ The Peruvians believed that they were descended from mountains and stones.” [5]

The fertility of stone is a well-known mythological motif; accompanied by such practices as ‘sliding’ (in which a woman rubbed her stomach against a stone surface), for the most part it remained confined to the female’s quest for offspring, as she sought to replenish herself by contact with the divine feminine of the earth. Alternately, conception was often attributed to the agency of ancestor spirits who were thought to reside in megaliths, waiting for the right woman to help them reincarnate. But an older, weirder process of sexualization of the inhuman has left a few traces: “Kings and clerics in the Middle Ages were constantly forbidding the cult of stones, and in particular the practice of seminal emission in front of stones. [It] results from a somewhat evolved conception of the sexualization of the mineral kingdom, of birth originating from stone and so forth, which corresponds to certain rites for the fecundation of stone.” [6] Rock and stone have long occupied places in fertility myths, and so Gorons, at least by connotation, are perhaps not as removed from the realm of reproduction as we might think — though they certainly are subject to different processes than the other mortal races.

In a society without females, but governed by the Life-giving Mother and in close relationship to the material of all being, the Gorons have entered into a socius (the social body which takes credit for material production) subsumed under the category of primitive territorial machine, where desire is inscribed directly on the Earth. This desire is anoedipal, incestuous, collective, and celibate all at once: a fraternity of bachelors. Even though there exist ascendants and descendants, all Gorons are first and foremost brothers, both in the order of filiation (they take their flesh from Death Mountain) and in the order of alliance (they need to prove their worth — even Gorons must become-Goron — and this trial is always available for aliens to gain admission into their extended family). Thus, because all beings take their existence from the earth, at least in some sense, each being is tied to the Goron inextricably: and if a being wishes to enter into recognized brotherhood with the Goron, then it need only prove itself worthy. No other society in Hyrule is so broad-minded or so beautifully, refreshingly unfamiliar to the concept of the “other”.

End Interlude

“What is it to have a rock nature? This question puts our mind in a petromorphic state.” [2]

If the multiplicity of races sharing the world of The Legend of Zelda didn’t exist, the Hylian imagination would have needed to invent them. They are lines of flight from a State machine that is perpetually in the process of reconstituting itself. Mythically predicated on a recursive, ontologizing struggle against chaos, it places a high value on overcoding and reterritorialization as translatio imperii. Through all their vicissitudes in time and space, Castle, Temple, and Lost Woods impose meaning on the land, distribute religious and political power, and superpose the bright shadow of the Sacred Realm on the finite world, tracing a path only Hylia’s chosen can walk. Yet the same Hero that acts as cultural ambassador to enlist the support of the races under the aegis of a single royal house can do so only by traversing all the planes and affirming all becomings: inviting the player in turn to become-scrub, become-fish, become-woman, become-rock, transformations most solidly expressed in games like Majora’s Mask, wherein Link becomes envoy to the disparate races of Hyrule by becoming them.

Among the races capable of forming assemblages with the Hylian majority in creative becomings, Gorons are the most alien and uncanny, and the most powerful and exhilarating. The full body of the Earth is the Goron desiring-machine and production-machine, hearkening “. . . back to a time before the man-nature dichotomy, before all the coordinates based on this fundamental dichotomy have been laid down. He does not live nature as nature, but as a process of production. There is no such thing as either man or nature now, only a process that produces the one within the other and couples the machines together.” [3] Gorons are both producers and product, caught in a utopian cycle that satisfies all their needs with the least possible number of variables; as such, even as they remain embedded in their territoriality, they represent the absolute limit that is a constant opportunity and invitation to experiment for all Hyrulean races: “the unequal, the coarse, the rough, the cutting edge of deterritorialization.” [4] For anyone, then, that desires to be something other than they are — to experience newness through breaking down old ways of being, recreating themselves in the process — the Goron stands as testament to the possibility of transformation.

And there are many other frameworks for understanding the peculiar allure Gorons hold for us. The lithic hybridization of our imagination brings us back to primeval fancies of autochthonous birth, at-one-ness with the substance of the landscape, and erotic involvement with the living rock. The question almost begs itself: just how do Gorons reproduce? The absence of female Gorons must not lead us to postulate an estrangement from the feminine. Foreclosed from association with the opposite gender, the sons of stone may be even closer to the archetypal feminine in its petric, chthonic aspect: the strong- and red-armed mother Din who dances and stomps tectonic plates into chains of mountains: petra genitrix, matrix mundi. We see no shortage of world myth in which humanity springs forth from the earth “. . . engendered by a chthonian Great Goddess . . . the Armenians thought the earth was the ‘maternal womb, whence men came forth.’ The Peruvians believed that they were descended from mountains and stones.” [5]

The fertility of stone is a well-known mythological motif; accompanied by such practices as ‘sliding’ (in which a woman rubbed her stomach against a stone surface), for the most part it remained confined to the female’s quest for offspring, as she sought to replenish herself by contact with the divine feminine of the earth. Alternately, conception was often attributed to the agency of ancestor spirits who were thought to reside in megaliths, waiting for the right woman to help them reincarnate. But an older, weirder process of sexualization of the inhuman has left a few traces: “Kings and clerics in the Middle Ages were constantly forbidding the cult of stones, and in particular the practice of seminal emission in front of stones. [It] results from a somewhat evolved conception of the sexualization of the mineral kingdom, of birth originating from stone and so forth, which corresponds to certain rites for the fecundation of stone.” [6] Rock and stone have long occupied places in fertility myths, and so Gorons, at least by connotation, are perhaps not as removed from the realm of reproduction as we might think — though they certainly are subject to different processes than the other mortal races.

In a society without females, but governed by the Life-giving Mother and in close relationship to the material of all being, the Gorons have entered into a socius (the social body which takes credit for material production) subsumed under the category of primitive territorial machine, where desire is inscribed directly on the Earth. This desire is anoedipal, incestuous, collective, and celibate all at once: a fraternity of bachelors. Even though there exist ascendants and descendants, all Gorons are first and foremost brothers, both in the order of filiation (they take their flesh from Death Mountain) and in the order of alliance (they need to prove their worth — even Gorons must become-Goron — and this trial is always available for aliens to gain admission into their extended family). Thus, because all beings take their existence from the earth, at least in some sense, each being is tied to the Goron inextricably: and if a being wishes to enter into recognized brotherhood with the Goron, then it need only prove itself worthy. No other society in Hyrule is so broad-minded or so beautifully, refreshingly unfamiliar to the concept of the “other”.

End Interlude

But if we are indeed allowing that Link puzzles about these things, he is likely soon torn away from his reveries as the landscape develops in beauty and austerity around him. The pathway that skirts along the eastern side of Trilby Valley is gentle, though it eventually proffers sojourners up to the Maw of Death Mountain, a strip of parched land among hot springs and pools of glowing lava. The Maw is marked by a series of naturally-occurring stone archways, reminiscent of such spans as the Rock Bridge of Kharaz in Jordan or the myriad natural arches of the American Southwest, like the Rainbow and Corona arches of Utah. (The largest and perhaps most impressive of the natural arches is the Xianren Qiao [fairy bridge] of Guangxi Province in southern China, though it lacks the geologic similarities and colorations as those found near Death Mountain.) And it is on these arches that we see the first signs of an environment changed by a living being. Large metal beams protrude from the underside of the initial arch, and these beams support metal plates that have been painted red with blotchy white designs. As we continue up the path, under these cascading arches of stone with their industrial flare, almost all life disappears; trees fall away, as do grasses and flowers, and all that is left is a lava-burned ground framed by rust-colored walls of stone. Sconces holding glowing red stones light the way forward, and occasionally the path is marked by iron plates sunk into the ground, usually in groups of twos or threes, like planks of wood on a walkway. At times, two inscrutable marks make an appearance on the path: two intersecting metal planks forming a Greek cross, and, painted onto certain planks, a white circle of paint with a white dot inside. These strange signs lead the visitor ever onward, and eventually to one of the most intriguing and flummoxing parts of the path: a vertical cliff-face strewn with red-veined lava rocks. Link, with his stamina and training, is able to scale this wall, but as it is not particularly conducive to tourists arriving in the city, we might think that it was a rockslide caused by the rampage of the Divine Beast. Otherwise, this indulgence of nature-as-pathway far exceeds even the Zora.

Corona Arch in Utah, USA — Image Credit: Michael Grindstaff / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

Not far along the trail we come to the first major signs of a society at work — though far different from what we have seen elsewhere. And nearly everything constructed by the Gorons seems to relate to their two primary industries: tourism and mining. The Goron Group Mining Company, founded by their Chief, Bludo, is the lifeblood of the Goron economy, employing most of the working-age Gorons in the city, and supporting the city’s development. [7] While Gorons consume some of the excavated stone from their mines, all gemstones — which once were thought to be worthless — are sold to the other peoples of Hyrule. The GGMC historically operated only one mine to the north of the city, but eventually the furnaces at Darunia Lake were abandoned as threats increased in the wake of Vah Rudania’s rampage. Continued mining became untenable as great volumes of lava cascaded into the area, making it too hot for even most Gorons to work comfortably; coupled with monsters that began to appear among the rocky islands of the lake, it proved too hard to protect the miners, and thus it was abandoned. Once Vah Rudania claimed the summit and the North Mine was deserted, the Gorons turned toward the south of their city for their continued work. In this small, ash covered valley, the GGMC has set up its new base of operations. Metal has been wrapped around rocks, marking the territory, and two structures are easily recognized: a metal bridge across a lava-flow, and a rough lean-to or shanty made of large metal beams. And the Gorons are here hard at work; while the children roll around, careening between formations of stone, the grown-ups wield pickaxes at stone that is rich in flint, rock salt and amber. How much of this raw material is useful to Gorons is unknown, and not just any rock is edible, after all.

Interlude: Inhuman Architecture

At first sight, Goron architecture reads like an oxymoron. It would seem there is nothing to investigate here, but we can approach the topic from two different and complementary angles: that of the primary world in which game designers are ‘virtual’ architects, and that of the secondary world in which Gorons make a statement about the earth that may not be obviously architectural, but resonates powerfully with the art brut of the 20th century and the emerging environmental humanities.

Coding architectural spaces, be they smooth tunnels or soaring cathedrals, is the simplest and commonest performance in environment design: at its origins it merges with level design in the construction of functional networks. But any complex 3D representation that offers itself to distracted and repetitive engagement and inhabitance is architectural to the second degree. Walter Benjamin, in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, makes note of this almost accidental encounter with architecture — the architecture which surrounds us all the time, framing our activities, but which goes largely unnoticed, writing: “Architecture has always offered the prototype of an artwork that is received in a state of distraction . . . Buildings are received in a twofold manner: by use and by perception. Or, better: tactilely and optically . . . Tactile reception comes about not so much by way of attention as by way of habit. The latter largely determines even the optical reception of architecture, which spontaneously takes the form of casual noticing, rather than attentive observation.” [8]

As everyone knows, Breath of the Wild is the first Zelda game to feature detailed terraforming over great expanses of rock. Spectacular proportions and dizzying verticalities are paired with craggy, corrugated, irregular surfaces in the most canonical synthesis of the Sublime. Enormous amounts of data have been crunched to produce the appearance of materic randomness, while the design process itself has been randomized into vertiginous redundancy and excess. Goron City, minimally altered by art, epitomizes this aesthetic choice and carries it to its extreme conclusions. Although Gorons have intervened here and there, arranging bridges, walkways, and railings, there is little to justify a reference to ‘earthworks’ and ‘land art’, and few attempts have been made to make the landscape meaningful. Artistry has been stripped to the essential ethological function of marking a territory, brought brusquely back to its grounding. The Gorons have made a stage with their inborn matters of expression. And yet they exhibit no concern for the preservation of their habitat as fetishized beautiful landscape: proudly displaying the signs of their industry and technical ingenuity, all their devotion is centered around the earth as food source and putative parent. But does something so seemingly makeshift and unfashioned constitute art proper? “Can this becoming, this emergence, be called Art? That would make the territory a result of art. The artist: the first person to set out a boundary stone, or to make a mark . . . the signature is . . . the chancy formation of a domain . . . [I]t is with the abode that inspiration arises. No sooner do I like a color that I make it my standard or placard. One puts one’s signature just as one plants one’s flag on a piece of land.” [9]

If there is an artistic mind at work in the land of the Gorons, that artist is Death Mountain itself, its tools erosion, sediment, explosion, and landslide. But this should come as no surprise, as art has long ceased to be exclusively understood as a privilege of humans or even living beings. Matterism (Haute Pâte, Pittura Materica), a subset of Informalism, took the slow, unconscious artistry of inhuman subjects as its point of departure. Artists like Alberto Burri strove to efface the human touch in works that are at once tribute, appropriation, and interrogation of ‘Nature’. The graphic design of Goron City can be seen as a latter day ‘digital matterism’ applied to environmental architecture. And in place of an aesthetic paradigm which has man acting upon nature — the active shaping the purely passive — we are instead given view of a world in which “Creating art with stone is not the domestication of an element, but a human-lithic collaboration that recognizes the art stone already holds.” [10]

Back to our Deleuzian turn, the virtual Earth of Death Mountain is a destratified field of immanence, a territory strewn with pure intensities in continuous variation. At this level of finesse, game design mimics a natural coding that operates independently of overarching symbolic structures. The boulders, air currents, and flows of lava that compose and modulate this landscape are so many a-signifying signs; they allow the player to create infinitesimal, unrepeatable game states. Whereas translating a template into precise polygons constitutes a tracing and an overcoding, generating the terrain following loose geological principles is more like a map and a decoding — environment design as an experimental and abstract machine. How does one inhabit such a stonescape? In contrast to the imperial architecture of Hylians, Gorons follow the flow of matter. The rock-born thrive in their strange fellowship with ore, sediment, lava, and all the various materials of creation, bringing about an environment that is at once touched and untouched by any affect of artistry. It is altogether another kind of architecture, if it can be said to be one at all.

End Interlude

At first sight, Goron architecture reads like an oxymoron. It would seem there is nothing to investigate here, but we can approach the topic from two different and complementary angles: that of the primary world in which game designers are ‘virtual’ architects, and that of the secondary world in which Gorons make a statement about the earth that may not be obviously architectural, but resonates powerfully with the art brut of the 20th century and the emerging environmental humanities.

Coding architectural spaces, be they smooth tunnels or soaring cathedrals, is the simplest and commonest performance in environment design: at its origins it merges with level design in the construction of functional networks. But any complex 3D representation that offers itself to distracted and repetitive engagement and inhabitance is architectural to the second degree. Walter Benjamin, in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, makes note of this almost accidental encounter with architecture — the architecture which surrounds us all the time, framing our activities, but which goes largely unnoticed, writing: “Architecture has always offered the prototype of an artwork that is received in a state of distraction . . . Buildings are received in a twofold manner: by use and by perception. Or, better: tactilely and optically . . . Tactile reception comes about not so much by way of attention as by way of habit. The latter largely determines even the optical reception of architecture, which spontaneously takes the form of casual noticing, rather than attentive observation.” [8]

As everyone knows, Breath of the Wild is the first Zelda game to feature detailed terraforming over great expanses of rock. Spectacular proportions and dizzying verticalities are paired with craggy, corrugated, irregular surfaces in the most canonical synthesis of the Sublime. Enormous amounts of data have been crunched to produce the appearance of materic randomness, while the design process itself has been randomized into vertiginous redundancy and excess. Goron City, minimally altered by art, epitomizes this aesthetic choice and carries it to its extreme conclusions. Although Gorons have intervened here and there, arranging bridges, walkways, and railings, there is little to justify a reference to ‘earthworks’ and ‘land art’, and few attempts have been made to make the landscape meaningful. Artistry has been stripped to the essential ethological function of marking a territory, brought brusquely back to its grounding. The Gorons have made a stage with their inborn matters of expression. And yet they exhibit no concern for the preservation of their habitat as fetishized beautiful landscape: proudly displaying the signs of their industry and technical ingenuity, all their devotion is centered around the earth as food source and putative parent. But does something so seemingly makeshift and unfashioned constitute art proper? “Can this becoming, this emergence, be called Art? That would make the territory a result of art. The artist: the first person to set out a boundary stone, or to make a mark . . . the signature is . . . the chancy formation of a domain . . . [I]t is with the abode that inspiration arises. No sooner do I like a color that I make it my standard or placard. One puts one’s signature just as one plants one’s flag on a piece of land.” [9]

If there is an artistic mind at work in the land of the Gorons, that artist is Death Mountain itself, its tools erosion, sediment, explosion, and landslide. But this should come as no surprise, as art has long ceased to be exclusively understood as a privilege of humans or even living beings. Matterism (Haute Pâte, Pittura Materica), a subset of Informalism, took the slow, unconscious artistry of inhuman subjects as its point of departure. Artists like Alberto Burri strove to efface the human touch in works that are at once tribute, appropriation, and interrogation of ‘Nature’. The graphic design of Goron City can be seen as a latter day ‘digital matterism’ applied to environmental architecture. And in place of an aesthetic paradigm which has man acting upon nature — the active shaping the purely passive — we are instead given view of a world in which “Creating art with stone is not the domestication of an element, but a human-lithic collaboration that recognizes the art stone already holds.” [10]

Back to our Deleuzian turn, the virtual Earth of Death Mountain is a destratified field of immanence, a territory strewn with pure intensities in continuous variation. At this level of finesse, game design mimics a natural coding that operates independently of overarching symbolic structures. The boulders, air currents, and flows of lava that compose and modulate this landscape are so many a-signifying signs; they allow the player to create infinitesimal, unrepeatable game states. Whereas translating a template into precise polygons constitutes a tracing and an overcoding, generating the terrain following loose geological principles is more like a map and a decoding — environment design as an experimental and abstract machine. How does one inhabit such a stonescape? In contrast to the imperial architecture of Hylians, Gorons follow the flow of matter. The rock-born thrive in their strange fellowship with ore, sediment, lava, and all the various materials of creation, bringing about an environment that is at once touched and untouched by any affect of artistry. It is altogether another kind of architecture, if it can be said to be one at all.

End Interlude

The main attraction on this route to Death Mountain is Goron City, built around, and hovering over, an actively-burbling pool of lava. Red motes of cinder rise continually from the ground, giving the very impression of heat. The city is a multitiered settlement with two main layers, and the main road wraps around the heart of the city which sits above the lava on a series of metal crossings. It feels strange to describe the various houses and shops around the city as “buildings”, for it is almost like they simply morphed into their current shape, via tectonic shifts, lava flows, and rockfalls. They seem, in their basic forms, to be totally at-one with the natural landscape of Death Mountain; the only reason that we know them to have been crafted is due to their embellishments of paint and metal. Strong metal beams, as we have seen from the first instance of the Goron artistic spirit, and like the flaming arms of Din, seem to support almost everything touched by Goron hands. Their bridges are solid metal, their mine carts ride along metal tracks, and their roofs are braced by sturdy metal beams. The other component to these shelters, then, is the stone of the mountain, which forms walls, ceiling, and floor. Indeed, they have built shelters from the body of their Mother, so that they are fully nourished — in food and safety — by her in every sense of the word.

The houses are roughly domelike, with various supports, and focus around a central object at the dwelling-heart (though this object is different for each Goron home); some center around a game of tic-tac-toe, some a table, and others a hearth. Around this central hub is the Goron equivalent of a hallway, being a rutted circle by which they make their way around the house. It is interesting to see this basic pattern in both the Goron dwelling and in Goron art, for it is one of the two major symbols of this race. While the most obvious symbol is the Goron’s Ruby, like a stylized torch or rising fire, this second symbol — that of the dot within the circle — is equally present in the territory of Death Mountain. And while this pattern might not have sprung from the Goron imagination as a divine symbol (or a symbol of anything per se), it could have arisen relative to the physical movement of the Gorons around their dwellings. In that case, it is something born rather unconsciously out of biology — an instance or acknowledgement of teleonomy rather than teleology.

This pathway allows them to get to any implement they might need, being as these are arrayed around the doming walls of the house. In this outer ring, we find tables made of large, iron plates, upon which are to be found sake bottles, bowls, vases (with accompanying “flowers” of metal stems and rock petals), kettles, mugs, construction hats, and candles. Present in each home are crates full of stone, which are likely the equivalent of the Goron pantry, and shallow beds which are almost nest-like in appearance, with a small ramp leading in, leading to the inevitable conclusion that Gorons quite literally do “roll out of bed”. But by far the most intriguing thing to be found in every dwelling is the small shrine which houses the symbol of the Goron’s Ruby, and, through that symbol, their Mother, Din. The shrine is vaguely Japanese in form, though with obvious Goron embellishment; a false roof shelters the Ruby symbol, which is flanked by two small cairns, and under that are two bottles of sake and hanging pieces of decorative, white-painted metal. As the designers are quick to point out, what the Goron spirit lacks in finesse and elegance, it makes up for in simplistic charm and an embodied joie de vivre that overcomes any negativity. [11] As we have said, they are the only people that completely and fully give of themselves to strangers, and it seems that none of the sentient races of Hyrule are barred from their fraternity.

This pathway allows them to get to any implement they might need, being as these are arrayed around the doming walls of the house. In this outer ring, we find tables made of large, iron plates, upon which are to be found sake bottles, bowls, vases (with accompanying “flowers” of metal stems and rock petals), kettles, mugs, construction hats, and candles. Present in each home are crates full of stone, which are likely the equivalent of the Goron pantry, and shallow beds which are almost nest-like in appearance, with a small ramp leading in, leading to the inevitable conclusion that Gorons quite literally do “roll out of bed”. But by far the most intriguing thing to be found in every dwelling is the small shrine which houses the symbol of the Goron’s Ruby, and, through that symbol, their Mother, Din. The shrine is vaguely Japanese in form, though with obvious Goron embellishment; a false roof shelters the Ruby symbol, which is flanked by two small cairns, and under that are two bottles of sake and hanging pieces of decorative, white-painted metal. As the designers are quick to point out, what the Goron spirit lacks in finesse and elegance, it makes up for in simplistic charm and an embodied joie de vivre that overcomes any negativity. [11] As we have said, they are the only people that completely and fully give of themselves to strangers, and it seems that none of the sentient races of Hyrule are barred from their fraternity.

Interlude: Queer Ecology

“Stone rebukes epistemology. In that reproach inheres a trigger to human creativity and a provocation to cross-ontological fellowship.” [12]

Neither human nor inhuman, Gorons embody a dream of continuity and solidarity between people and stones. From the standpoint of an external observer, they can be seen as a mythopoetic thought experiment within the scope of Hylian legends that enables humans to breach ontological divides, freeing “the petric in the human and the anthropomorphic in the stone.” [13] These gruff rock-eaters are radically inclusive of strangers, mindful of their common origin in the earth, at however many removes: as Daruk triumphantly observes in his training journal: “I knew Hylians could eat rocks too.” Maybe this aptitude for bonding is the Gorons’ most valued contribution to the Hyrulean alliance: advocates for a disanthropocentric vision, they hold other proud and storied races together by binding them firmly to their shared materiality: a living refutation of what Manuel De Landa terms ‘organic chauvinism’, or the tendency of living beings to look down upon the inanimate or non-conscious. This theme resonates with recent developments in the field of inquiry known as ‘queer ecology’. As Mel Y. Chen writes in Animacies: “[S]tones and other inanimates definitively occupy a scalar position (near zero) on the animacy hierarchy . . . they are not excluded from it altogether and are not only treated as animacy’s binary opposite. New materialisms are bringing back the inanimate into the fold of Aristotle’s animating principle . . . animacy as a specific kind of affective and material construct that is not only nonneutral in relation to animals, humans, and living and dead things, but is shaped by race and sexuality.” [14]

Thus by eating, manipulating, and dwelling in strange intimacy with rocks and ores, Gorons act as catalysts for their agency and animacy: they accelerate their metamorphosis, enter into composition with them, propel them into wider circulation, and make them culturally available to outsiders as products of their smithcraft and engineering.

End Interlude

“Stone rebukes epistemology. In that reproach inheres a trigger to human creativity and a provocation to cross-ontological fellowship.” [12]

Neither human nor inhuman, Gorons embody a dream of continuity and solidarity between people and stones. From the standpoint of an external observer, they can be seen as a mythopoetic thought experiment within the scope of Hylian legends that enables humans to breach ontological divides, freeing “the petric in the human and the anthropomorphic in the stone.” [13] These gruff rock-eaters are radically inclusive of strangers, mindful of their common origin in the earth, at however many removes: as Daruk triumphantly observes in his training journal: “I knew Hylians could eat rocks too.” Maybe this aptitude for bonding is the Gorons’ most valued contribution to the Hyrulean alliance: advocates for a disanthropocentric vision, they hold other proud and storied races together by binding them firmly to their shared materiality: a living refutation of what Manuel De Landa terms ‘organic chauvinism’, or the tendency of living beings to look down upon the inanimate or non-conscious. This theme resonates with recent developments in the field of inquiry known as ‘queer ecology’. As Mel Y. Chen writes in Animacies: “[S]tones and other inanimates definitively occupy a scalar position (near zero) on the animacy hierarchy . . . they are not excluded from it altogether and are not only treated as animacy’s binary opposite. New materialisms are bringing back the inanimate into the fold of Aristotle’s animating principle . . . animacy as a specific kind of affective and material construct that is not only nonneutral in relation to animals, humans, and living and dead things, but is shaped by race and sexuality.” [14]

Thus by eating, manipulating, and dwelling in strange intimacy with rocks and ores, Gorons act as catalysts for their agency and animacy: they accelerate their metamorphosis, enter into composition with them, propel them into wider circulation, and make them culturally available to outsiders as products of their smithcraft and engineering.

End Interlude

Rohan, the smith, hard at work at his forge.

As has been said, the other bedrock industry of Goron City is tourism, which is supported by a wide range of local businesses and shops. Master Rohan runs a smithy in town, which keeps the old arts alive; the Goron Gusto Shop is the town’s general store; Protein Palace is an outdoor barbecue joint that specializes in grilling food for tourists; Ripped and Shredded is the armor shop managed by Rogaro and Pyle (who was recently laid off from his mining job, we come to find) which sells the wares that the blacksmith, Rohan, crafts from gems from the mines; lastly, and most clever, is the Rollin’ Inn, which also serves as the beating heart of the “art of Goron massage” which can leave one “sleeping like a rock” and “feeling loose as gravel”. What is continually interesting is that Gorons need almost nothing produced by their economy. Their necessary economy centers around mining for stones to eat, and this appears to be just a highly-mechanized form of foraging. Granted, basic tools are used to gather the earth’s flesh, but aside from this the entire economy works for the tourist. What does the average Goron seem to need, aside from rock and shelter? (Though shelter too seems something not strictly necessary, as Gorons appear to be equally happy under the stars.) The Gorons are a strange riddle of a people, and they seem, to some extent, to have normalized the idea of an economy without really having the need for it: it is an adopted, performative game that the Gorons seem to have developed out of respect or convenience for their fellow beings. But it is hard to imagine that these cultural phenomena (which have come into being only after the Great Calamity) are indigenous to the Goron spirit.

The most set-apart structure in the city is the house of Bludo, chief of the Gorons for at least the past century. It is a good touchstone for Goron living, and the designers have this to say about both his house and the Gorons in general: “Goron City is home to the Goron miners, who absolutely love metal and stone. I designed the house of the head of the town, Boss Bludo, to be symbolic of the Gorons. It incorporates a giant boulder, signifying that he is a man among men and that he is comfortable even in the scorching heat of magma. However, I would not have been able to express the unique charm of the Gorons solely through the austerity of mining, so by adding contrasting elements that show that they like cute things (toys, etc.), I was able to demonstrate their slightly timid, softer side as well.” [15] So, to the already-complex Goron we can now add a very traditional hyper-masculinity and the counterpoint of liking that which is adorable. But we are here focused upon the architectural statement, which concerns the integration of architecture into social prestige and its hierarchical overlay. Like Daruk’s house, which is a temple to proper physique, Bludo’s house, with its rising chimneys of rock, is immediately noticeable as precarious — symbolizing the extraordinary strength requisite for a leader. Upon entering, we can immediate set this house apart from all others; rivulets of lava break the home into different spaces, where small bridges give access to a small sleeping alcove and a petite dais upon which the chief assumedly does his chiefly duties. The throne is marked by a series of handprints in red paint, and like the immense rock above, which bears the symbol of the Goron, so too is the dais adorned with a tribute to Din’s stone. As unique as they are among the peoples of Hyrule, even the Gorons are not without the trappings of power.

The last things to note about Goron City are those things which rise above it: noticeably Stolock Bridge and the monumental sculpture to Goron Heroes. As the pathway wraps around the two levels of Goron City, it eventually leads past the abandoned North Mine, and over a massive bridge which leads onward to the Goron Hot Springs and finally Death Mountain itself. This bridge is called Stolock Bridge, and it is partially suspended by, yet partially stems from, the colossal sculpture overhead. The sculpture commemorates four of the most well-known Gorons in the series: Darmani III, the Elder’s Son (both of Majora’s Mask), Gor Coron from Twilight Princess, and, of course, the mighty Daruk, Champion of Hyrule. There are many reasons why a culture might create a monumental sculpture, such as is seen in Goron City. Many real-world cultures wish to aggrandize their accomplishments, or record a victory for posterity; these larger-than-life representations of heroes can instill a love of nation or instill fear in an enemy — oftentimes they serve both purposes. But monumental sculpture can also have a more transcendent and humanistic purpose, and that is one of education, humility, and gratitude. While monuments like the rock sculpture to Decebalus in Romania or Russia’s the Motherland Calls play on sentiments of national strength in the face of the external enemy, others remind us that, beyond the shrill cries of war and rancor, a deeper humanity is yet possible. Those that come immediately to the modern mind are statues like the Cristo Redentor in Brazil, the monument to Confucius at Mt. Ni in Qufu, or the several colossal statues to the Buddha across Asia. [16] And while these statues are not entirely free of political showmanship in all cases, they still embody fundamentally-deeper strands of human thought: cooperation, reflection, and serenity, among many other virtues. They serve as both reminders and touchstones of a shared bond, and while they allow us to pay respect to those that have come before, they simultaneously educe a respect for our fellow-travelers through life. In short, they represent and rouse what is most sublime in our potential. And just as humans have done, so too have the Gorons carved their moral paragons into the flesh of the mountain. Darmani and Daruk gave their lives in the service of others, attempting the salvation of a people; Gor Coron led his tribe during the ordeal of Chief Darbus’s enchantment, assisting Link in obtaining a piece of the Fused Shadow; and the Elder’s Son? Well, no one is quite sure. But that these Gorons are all exemplars of some virtue or another is beyond question. And so they loom over the city, keeping watch as generations are raised to become Gorons — an open challenge to all, as we have seen, because “being” a Goron seems more a mindset than anything else.

And what better place to end than a place where Gorons come to be? This place — the sine qua non of the Goron spirit — rests at the farthest northern reaches of the known world: Gut-Check Rock. This colossal tower of stone stands alone in a field dappled with hot springs and parched trees. Here, as close as Zelda ever gets to the concept of the holy within the athletic, the Goron Blood Brothers pursue their higher calling. These sworn brothers continually stress the importance of endurance and embodied strength, challenging Link to overcome his limits and embrace their training so as to become-Goron. To that end, Link must wend his way to the top of the rock in an ultimate test of stamina. And when he succeeds, he earns the right to call himself the fourth of the Goron Blood Brothers, winning not only the right to stand atop the sacred summit of the rock, but, like his predecessors of the ancient past, his initiation into the timeless brotherhood of the Goron.

Notes and Works Cited:

[1] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 123.

[2] Aswell Doll, Mary. “Chapter 3: The Living Stone.” The More of Myth: A Pedagogy of Diversion, Sense Publishers, 2011, p. 18.

[3] Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. “Chapter 1: The Desiring-Machines.” Anti-Oedipus, University of Minnesota Press, 1983, p. 2.

[4] Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. “1730: Becoming-Intense, Becoming-Animal.” A Thousand Plateaus, University of Minnesota Press,1987, p. 244.

[5] Eliade, Mircea. “Chapter 7: The Earth, Woman and Fertility.” Patterns in Comparative Religion, Sheed and Ward, 1958, p. 244.

[6] Ibid., “Chapter 6: Sacred Stones: Epiphanies, Signs and Forms”, p. 223.

[7] “Many of the Gorons living in Goron City are employees of the Goron Group Mining Company and make a living excavating and selling ore. Bludo, boss and founder of the company, noticed that the gemstones found around the volcano that they thought were worthless traded for a high price to other races. He started a thriving business selling these gemstones, and it developed into the largest enterprise among the Gorons. The profits from mining gemstones drive Goron City's economy, leading it to develop into the thriving city it is today.”

White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 123.

[8] Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin, translated by Edmund Jephcott, Rodney Livingstone, Howard Eiland, and Others, Harvard University Press, 2008, p. 40.

[9] Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. “1837: Of the Refrain.” A Thousand Plateaus, University of Minnesota Press, 1987, p. 316.

[10] Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. “Geophilia: The Love of Stone.” Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman, University of Minnesota Press, 2015, p. 61.

[11] “The Gorons’ furniture is made of nonflammable metal and stone. Since the Gorons are not the most skilled with their hands, the resulting craftsmanship lacks some finesse but ultimately gets the job done.”

White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 296.

[12] Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. “Introduction: Stories of Stone.” Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman, University of Minnesota Press, 2015, p. 8.

[13] Ibid., p. 10.

[14] Chen, Mel Y. “Introduction: Animating Animacy.” Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect, Duke University Press, 2012, p. 5.

[15] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 301.

[16] This site is considered to be Confucius’s birthplace, and is located near Qufu, in Shandong Province. It is interesting to note that the same party that oversaw the desecration of Confucian statuary, literature, and philosophy at the Confucian Temple in Qufu has recently allowed a far-larger statue to be built in homage to this school of thought. If you seek a sobering account of the details of this cultural annihilation, please see this article from China Heritage Quarterly.

[1] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 123.

[2] Aswell Doll, Mary. “Chapter 3: The Living Stone.” The More of Myth: A Pedagogy of Diversion, Sense Publishers, 2011, p. 18.

[3] Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. “Chapter 1: The Desiring-Machines.” Anti-Oedipus, University of Minnesota Press, 1983, p. 2.

[4] Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. “1730: Becoming-Intense, Becoming-Animal.” A Thousand Plateaus, University of Minnesota Press,1987, p. 244.

[5] Eliade, Mircea. “Chapter 7: The Earth, Woman and Fertility.” Patterns in Comparative Religion, Sheed and Ward, 1958, p. 244.

[6] Ibid., “Chapter 6: Sacred Stones: Epiphanies, Signs and Forms”, p. 223.

[7] “Many of the Gorons living in Goron City are employees of the Goron Group Mining Company and make a living excavating and selling ore. Bludo, boss and founder of the company, noticed that the gemstones found around the volcano that they thought were worthless traded for a high price to other races. He started a thriving business selling these gemstones, and it developed into the largest enterprise among the Gorons. The profits from mining gemstones drive Goron City's economy, leading it to develop into the thriving city it is today.”

White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 123.

[8] Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin, translated by Edmund Jephcott, Rodney Livingstone, Howard Eiland, and Others, Harvard University Press, 2008, p. 40.

[9] Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. “1837: Of the Refrain.” A Thousand Plateaus, University of Minnesota Press, 1987, p. 316.

[10] Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. “Geophilia: The Love of Stone.” Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman, University of Minnesota Press, 2015, p. 61.

[11] “The Gorons’ furniture is made of nonflammable metal and stone. Since the Gorons are not the most skilled with their hands, the resulting craftsmanship lacks some finesse but ultimately gets the job done.”

White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 296.

[12] Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. “Introduction: Stories of Stone.” Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman, University of Minnesota Press, 2015, p. 8.

[13] Ibid., p. 10.

[14] Chen, Mel Y. “Introduction: Animating Animacy.” Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect, Duke University Press, 2012, p. 5.

[15] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 301.

[16] This site is considered to be Confucius’s birthplace, and is located near Qufu, in Shandong Province. It is interesting to note that the same party that oversaw the desecration of Confucian statuary, literature, and philosophy at the Confucian Temple in Qufu has recently allowed a far-larger statue to be built in homage to this school of thought. If you seek a sobering account of the details of this cultural annihilation, please see this article from China Heritage Quarterly.