Stronghold of the Yiga Clan

"We of the Sheikah tribe have long been heralded as a people of great wisdom. Our technology became the key to sealing Ganon away during the Great Calamity, some ten thousand years ago. At one point, our technology was praised as the power of the gods . . . but eventually the people turned on it. Turned on us. Our creations came to be viewed as a threat to the kingdom. The Sheikah became outcasts, forced into exile. Some, like us, chose to cast off our technological advances and strove to live normal lives. Others fostered a hatred towards the kingdom that shunned them. These sad souls swore their allegiance to Ganon. They now call themselves the Yiga Clan. Their sole mission is to eliminate all who stand against Ganon. Please, dear hero . . . be careful out there."

— Cado

— Cado

The division between the Sheikah and Yiga represents a singular case study in Hyrulean history as to the choices people can make when confronted with adversity. Both tribes are distant reflections of one another, sharing much the same essence, but channeling the spirits of their peoples toward vastly-differing destinies. When faced with oppression at the hands of the Hylian majority, the then-united Sheikah split into two factions. One group remembered their legacy of service and connection to Hyrule, while the other, embittered, gave themselves unto anger and vengeance. Confrontation with adversity and prejudice is one of the telling marks of character. When suffering an injustice, do we react with humility and understanding, remembering that even those who oppress us are suffering some form of mental poison? Or do we reject their humanity, much like they rejected ours? Clearly, each road will lead to a starkly different outcome, and to those reading this with a clear head, it seems as though we all wish we could react in a way that befitted our common humanity. Yet, once an emotion arises — be it anger, frustration, or fear — this better angel of our nature is almost impossible to follow; once angered, we seek only to justify our anger, rooting it in moral language and injustice, which leads to a righteousness that oftentimes occludes our hopes for ourselves — how we believe we should think and act toward others in our best moments. I think there is a great deal this division between the Yiga and the Sheikah can teach, if we allow it. To clothe our abstractions in fiction, then, we need to attempt to penetrate the collective mindsets of both the Sheikah and the Kingdom of Hyrule in an age long past.

In Breath of the Wild, we quickly learn that, millennia ago, the Sheikah led the Hyrulean efforts to defend the kingdom against the inevitable return of Ganon; their technology was absolutely critical in his defeat ten thousand years in the past. With Ganon’s defeat, the Sheikah had once again fulfilled their charge to the Goddess Hylia in protecting the Royal Family and Kingdom of Hyrule. It seems that legend would hold such a victory in high regard. But this is a one-sided telling without historical rigor, because what we also discover is that this technology was far beyond the understanding of the Hyrulean people. With mechanical creations that could traverse any type of terrain, fire beams of unknown energy, and take to the skies in order to track enemies, and with Divine Beasts larger than even the tallest tree, it is wholly understandable that the citizens of Hyrule would feel either apprehension or outright fear toward such machines. And when the King, looking out from his castle’s highest keep, saw a forest of Sheikah Towers dotting the landscape, feeling out energies deep within the earth, a skepticism surely must have claimed his heart. About his castle, too, were built five massive pillars, ostensibly holding Guardians awaiting the defense of the fortress. Yet with this inscrutable technology surrounding him, which he neither understood nor completely trusted, what was he to do? And when his people came to him in fright, as they must have done at times, complaining of mechanical eyes searching the countryside, how would he respond? His duty, first and foremost, was to his people, and even though the Sheikah had taken a sacred oath to his kingdom’s protection, that oath lay hidden in the shrouds of time. What if the oath had lost its power? What if there were plots against him? What if he were to be usurped?

In Breath of the Wild, we quickly learn that, millennia ago, the Sheikah led the Hyrulean efforts to defend the kingdom against the inevitable return of Ganon; their technology was absolutely critical in his defeat ten thousand years in the past. With Ganon’s defeat, the Sheikah had once again fulfilled their charge to the Goddess Hylia in protecting the Royal Family and Kingdom of Hyrule. It seems that legend would hold such a victory in high regard. But this is a one-sided telling without historical rigor, because what we also discover is that this technology was far beyond the understanding of the Hyrulean people. With mechanical creations that could traverse any type of terrain, fire beams of unknown energy, and take to the skies in order to track enemies, and with Divine Beasts larger than even the tallest tree, it is wholly understandable that the citizens of Hyrule would feel either apprehension or outright fear toward such machines. And when the King, looking out from his castle’s highest keep, saw a forest of Sheikah Towers dotting the landscape, feeling out energies deep within the earth, a skepticism surely must have claimed his heart. About his castle, too, were built five massive pillars, ostensibly holding Guardians awaiting the defense of the fortress. Yet with this inscrutable technology surrounding him, which he neither understood nor completely trusted, what was he to do? And when his people came to him in fright, as they must have done at times, complaining of mechanical eyes searching the countryside, how would he respond? His duty, first and foremost, was to his people, and even though the Sheikah had taken a sacred oath to his kingdom’s protection, that oath lay hidden in the shrouds of time. What if the oath had lost its power? What if there were plots against him? What if he were to be usurped?

This speculation may seem idle, but we are simply trying to frame a case for the King’s actions so long ago: what must have gone through his head as he sent into exile the one people to which his had been entrusted for so long? One does not turn on an ally lightly, after all. So, we have now imagined a Hyrule increasingly gripped by mistrust and doubt, unsure of a people who, because of their technologies, seemed as gods. And as to the Sheikah? We have no knowledge of ulterior motives or plots, and to an historical eye, it seems as though they were simply fulfilling their duty. Not only do the Sheikah have a societal drive toward technological discovery [1], their sacred charge to protect Hyrule against evil aligned perfectly with their desire to research. And when personal ambition finds itself in unity to an external duty, the resulting effort can be tremendous. We can imagine a Sheikah people alive with passion, honing the Guardians’ capabilities, perfecting targeting systems, flight protocols, and finding ever-better ways of detecting evil’s return. To them, then, this livelihood was both oath and game intertwined. But as with many academics and specialists, translating motive and function to a wider public grows ever more difficult as one’s scientific knowledge grows deeper. It is not so simple to explain flight or trajectory to a largely pre-scientific people — and especially to a people who have come to doubt your intentions. This gap, then, must have grown rapidly, as knowledge grew on one side, while the other fostered distrust. It is ultimately unfair, looking back from the high tower of the Present, that the Sheikah should have been distrusted. They were simply fulfilling a charge given to them in ancient days by the Goddess Hylia, common deity to both peoples. But, for all its injustice, I hope we can understand this history while refraining from casting judgment. So it happened that the King could no longer abide this people and their technologies and cast them forth from his kingdom into exile. All advanced mechanics and research were forbidden in the kingdom, and these technologies were eventually buried by time. The Sheikah left the kingdom, forming a settlement which they called Kakariko Village, where they abandoned their research for many long years. There, they lived in harmony with their valley, tending crops and building a peaceable life.

But not all Sheikah chose this path.

But not all Sheikah chose this path.

While many Sheikah affixed their fate to the protection of order throughout the land, one renegade group channeled their regret and hurt not to healing but to chaos. These Sheikah, after facing persecution at the hands of those who they had guided and protected for centuries, found that these injustices were unforgivable. A life of service and dedication had ended in treachery and ignominy. And so they turned on their former allies. To that end, they swore off the Royal Family and Kingdom of Hyrule and gave themselves wholly unto the kingdom’s destruction. They retreated deep into the mountains of Gerudo Province, and from there set about collecting information, terrorizing travelers, extorting people from nearby villages, and, occasionally, murdering the innocent. [2] And as their plans to resurrect Ganon came closer to fruition, their plans grew ever more bold. A century ago, clan assassins, now calling themselves the Yiga, made multiple assassination attempts on Zelda and the Four Champions, though none were successful. But none of these failures shifted Yiga methods or goals, and their aim was still fixed on the death of the Princess and her Chosen Hero. To me, with the understanding we have, it is difficult to look upon the Yiga with anything other than compassion; they are suffering more than most from hatred and historical grievance. And though this does not absolve them of their crimes, it should at least lead us to a more human viewing of their suffering and its consequences.

During the time of Breath of the Wild, the Yiga forces are led by Master Kohga, who is the master of the stronghold, and who is bent to a single purpose: Link’s death. Even upon his defeat at the hands of the Hero, those sworn to him still dedicate themselves to the end of order in Hyrule, attempting Link’s assassination wherever they find him, often appearing as wandering merchants or travelers, causing mischief wherever they go. With all this knowledge in mind, we should be able to glean just that much more from the architectural design elements at play within the Yiga Stronghold.

During the time of Breath of the Wild, the Yiga forces are led by Master Kohga, who is the master of the stronghold, and who is bent to a single purpose: Link’s death. Even upon his defeat at the hands of the Hero, those sworn to him still dedicate themselves to the end of order in Hyrule, attempting Link’s assassination wherever they find him, often appearing as wandering merchants or travelers, causing mischief wherever they go. With all this knowledge in mind, we should be able to glean just that much more from the architectural design elements at play within the Yiga Stronghold.

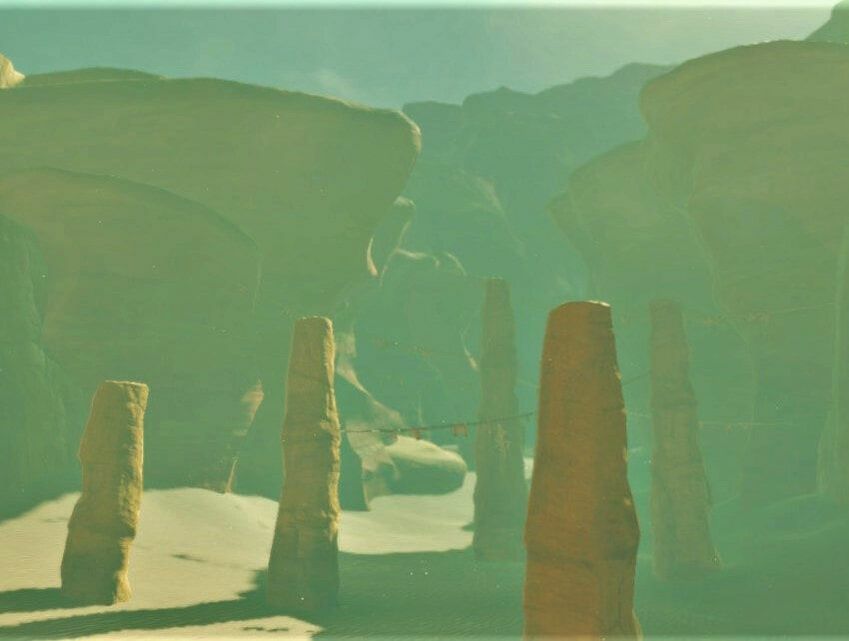

The Yiga base their clanhold in the far northern part of the Gerudo Desert, just where the flatlands begin transitioning into the bleak, arid Gerudo Highlands. The entrance to this base of operations is tucked in the higher part of Karusa Valley, a beautiful, shocking canyon of red sand-swept stone not dissimilar to certain canyons in the American Southwest. This area of Hyrule is arguably the most topographically interesting, with enormous peaks and chasmed valleys, carved into stone by millennial natural forces. Within this red landscape, under the etched-out sliver of blue sky above, the land begins to climb past narrowing cliffs and loose, tumbling sands. And it is here that we are first clued in to the Yiga Clan’s cultural ties to the Sheikah, for above us, stretching from one canyon wall to another, are many hundreds of the same wooden chimes seen in Kakariko Village with their myriad ropes and delicate sounds. Here, however, they are referred to as noisemakers, and are meant to warn the Yiga of intruders. And just like the perversion of these chimes into warning devices, so to has the Traveler’s Guardian Deity statue been twisted, with inverted symbolism, to show opposition and rebellion, for occasional faces have been masked over by a cloth bearing the inverted symbol of the Sheikah. The guardian statues are arranged in variously-sized groups, but they all stare straight into the canyon, so that any intruder will be taken in by hundreds of unfriendly eyes. So, instead of welcoming travelers to villages and rest, here they sit with hollow eyes in defensive and unfriendly masses. Around them, the wind flows boldly through the canyon, while small rivulets of sand cascade from on high. The final stretch of this crevasse is quite steep, with switchbacks (either natural or defensive) leading up to the higher terraces. These switchbacks are watched over by two tremendous rows of guardian statues, all staring downward at the rising path. And at the canyon’s end, so too is the entrance protected by these spirits, posted prominently with their sinister blindfolds.

Photo: Antelope Canyon, Arizona, United States — Image in the Public Domain

|

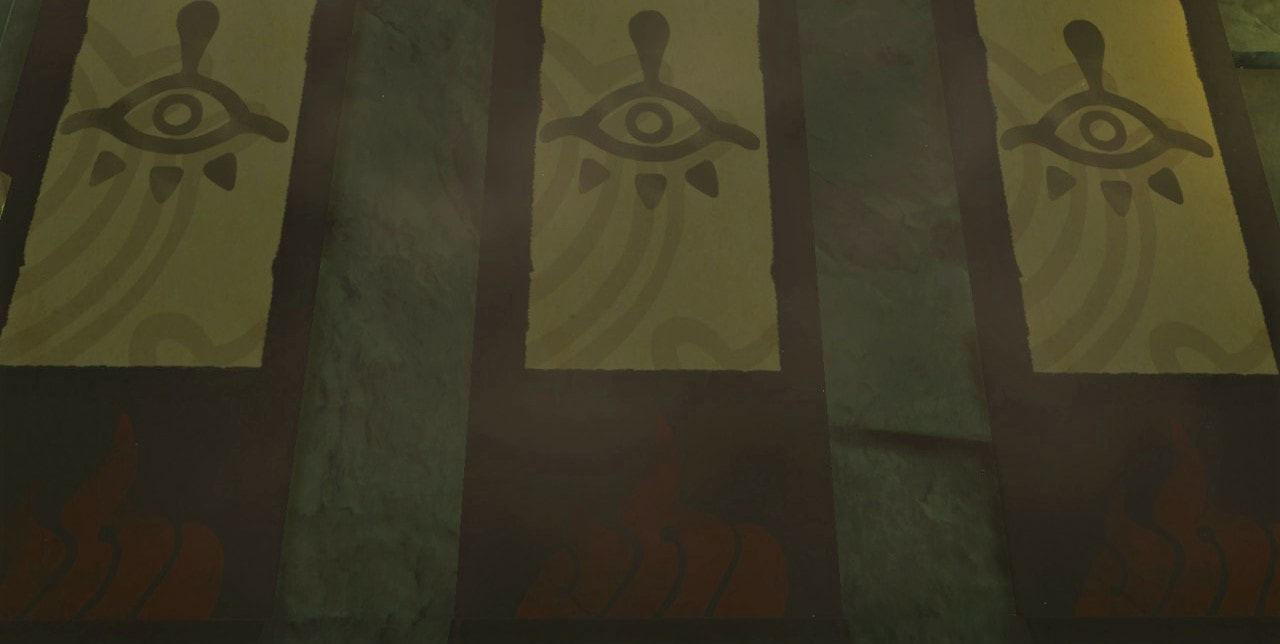

Left: Two Guardian Deity statues desecrated by Yiga blindfolds, each bearing the symbol of the Sheikah inverted: a sign of rebellion.

Above: The entrance to the Yiga stronghold at the far end of Karusa Valley; notice the proliferation of noisemakers and watchful statues. The hideout itself, which should be immediately noticeable, is actually an, “old Gerudo archaeological site that they snuck into and made their own.” The architectural influences here are derived from several distinct sources, among them certain traditional Japanese elements of aesthetics. [3] As in Kakariko Village, this stronghold maintains its Japanese roots, as both the Sheikah and Yiga stem from the same ancient source. Hence, we see many of the same design elements here as we did so long ago in Kakariko. |

The vestibule is a strange mix of styles, surrounded prominently by eight Gerudo statues, much like their larger counterparts farther south in the desert. Their faces have been covered with the same sacrilegious symbol of the Yiga, though they have not managed to efface this location entirely of its Gerudo origins. In the bays between the statues are giant relief panels adorned with Gerudo script which reads:

Gerudo

There

Is no

Strife

Gerudo

Like

Water

We Flow

With

Life

There

Is no

Strife

Gerudo

Like

Water

We Flow

With

Life

This message, proclaiming the peace and life-force of the Gerudo Civilization, is carved upon two distinct types of stone found in this cavern, though it may be that one stone was used as a later replacement during repairs. Along with the entrance in this octagonal room are seven radiating stairs beneath these large Gerudo epigrams, framed by the aforementioned statues. All but one are decoys, however, and end in short, hollowed-out passageways. The massive statues in this chamber are, like the epigrams, composed of two distinct types of stone: one sand-brown, the other dark grey. These female statues stand erect in long robes, carrying a sword pointed downwards, thrust into the ground. On the swords are carved more Gerudo words: Gerudo, an Unblemished Desert Flo . . . . This is all that can be read. Each woman bears a decorated neck-piece, done in red and blue paint. The statues wear a rather severe countenance, from what can be seen beneath the Yiga masks. Above these masks are distinctive pieces of headgear, boxlike in shape, which seem closest to those worn by the Yukatchu, or scholar-officials, that dominated the social hierarchy of the Ryukyuan Kingdom of the East China Sea. [4] With heads bowed slightly, these stone figures gaze upon a dais and floor of uneven stone, dark with Ancient Sheikah designs, connecting the Yiga to their ancient glory. Likewise are the bases of the statues covered in these same patterns, carved or painted atop the work of the Gerudo masons.

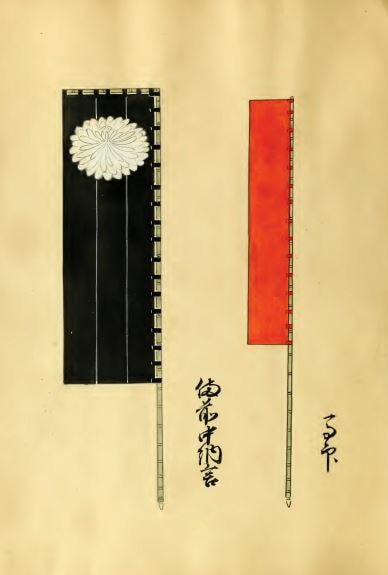

The true passage among these seven leads to a rough-hewn staircase in the stone which further passes to a small bridge over a lower hallway. A palisaded entrance (to a storage room), a small rug, and lamp-posts all pierce bleakly though the gloom of this complex, dimly lit by small lanterns and the glowing ofuda, Japanese wards for purification or protection, hung upon the walls. The passageway constricts and descends to follow the lower pathway, leading downward by a set of stairs to the right of the palisade. The stone has a quarried feel to it, given the rectilinear cuts differentiating each stone, though few stones are the same shape or size. Hugging the walls throughout these initial passages are strings of noisemakers and Guardian Deities, another homage to the past. Several doors are framed by decorative gates, as one would see at the approach to a shrine, though these simply lead to further underground chambers. Embellishments new to the Yiga are the uma-jirushi or sashimono banners, which were large flags used to denote important feudal warlords (daimyō) and their soldiers respectively. These entry-gates are among the most decorated artifacts in the Yiga Clan-hold, fitted with delicate lanterns, ornamental rope, and hanging banners of red fabric. We should feel almost at home among these designs of the Sheikah, and yet something about them is a bit off — the coloring, maybe, or the angle, or the way the shadows of the cavern play off the lanterns, making them look almost sickly in the yellow light. Even with such a cultural consonance still existing between these two peoples, this compound showcases artifacts that are distinctly Yiga in their make and effect. It is a darker, stranger side to Sheikah design.

|

Left: Uma-jirushi battle standard from the Battle of Sekigahara of 1600 — Image in the Public Domain, published online by Brigham Young University.

Above: Though not a battle standard, as they bear no insignia, these uma-jirushi-style banners can be found flanking several gates within the Yiga compound. Note: Anyone interested in vexillology or emblem studies should do a quick search for the Hōjō clan of Japan. |

The central chamber is the grand synthesis of many features, with a distinct upper and lower hall. The upper hall, accessible by ladder, is as the promenade of a Japanese bathhouse, suspended and airy, even though underground. The wood-framed windows and latticework open the second story to the scene below, making it feel larger than it truly is. Red lanterns give off a neon-nighttime glow, as if lights in a modern city. Below, the floor is awash with random stone barriers surrounding a tall central platform. All the familiar design elements are present, from lanterns and flags to the red rugs, ropes, and noisemakers seen ubiquitously elsewhere. And here too do the ofuda glow watchfully upon the walls.

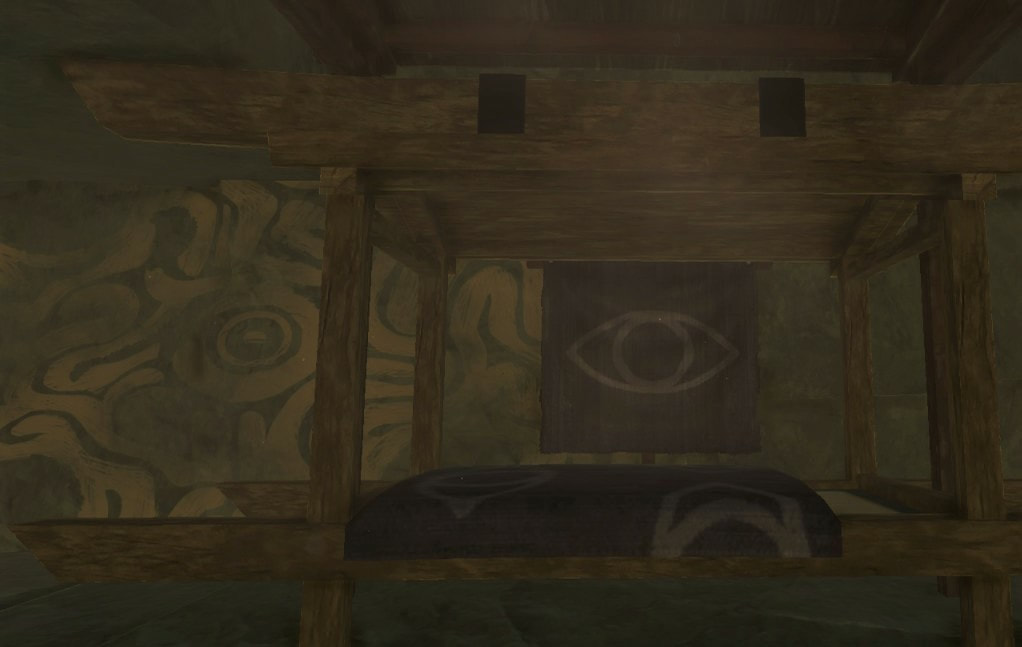

The final room appears to be an audience chamber, featuring prominently a sort of dais or stage for hearings and petitions. Here too are found drums, likely serving a ceremonial purpose — perhaps for announcements (or pronouncements). Masked Guardian Deity statues line parts of the wall, while others are lined with raised platforms, like a Zen meditation hall. Upon these platforms are found many daily-use items, such as mats, trays, papers, brushes, charms, and small bowls, likely for ink. One of the most interesting things about this room is its “roof”. Hanging down by four suspended posts is a roof which rests over the platform below it, tiled with wood and draped with fabrics bearing the wave patterns of the Ancient Sheikah. It hangs weightily beneath the ceiling of the cave, bearing strings of lanterns and other decorations. We can firmly state that the Yiga have made their cave as close to an outdoor village as possible, lining rooms like open-air streets, using windows and gates to frame areas of interest, and shaping the ceiling to look like the sky overhead. This simulacrum is understandable in its intention, though it is ultimately off-putting. Further in this vein is a small, roofed structure, like a pavilion, which stands in the audience chamber. This is likely where Kohga spends his time, at the heart of this austere complex. This smaller building is upon a slightly-raised platform, looking out over the room, holding a bed under a picture of a plain eye — neither Sheikah nor Yiga. Why this symbol is present only here is unknown.

Beyond a hidden doorway is almost a coliseum carved into stone. A hole open to the sky, surrounded by striated cliffs of orange and red, this massive cleft in the mountains centers on a ceremonial pit, surrounded by far-flung strings of noisemakers and small architectural settings bearing lanterns. The largest architectural piece is a two-story gate that leads forth from Master Kohga’s chamber, fully decorated in ribbons, lanterns, and a stark and watchful Yiga symbol. Everything in this natural hollow points toward the center, where the ground opens to an unfathomably deep pit. The pit has been surrounded in worked stone, bearing markings and designs, which gives the impression of its having some sort of sacral function. Ultimately, it is beyond us, though Kohga seems to think it important enough to adorn with decoration and symbol. And, in his hubris, it ends up being his tomb. Kohga’s tragicomic ending at his own hands brings us once more to the philosophical exploration presented at the beginning of this article; what are we to make of those who fall into wrongdoing? It is easy to laugh at Kohga, or find his ending both sensible and just, but it is much harder to view him as a human, and not as a simple caricature — as though an actor on a stage. We forget what societal and psychological forces led him to this point, twisting his perception and driving him toward desperation and violence. It is morally simplistic to view him solely as someone who is “evil”, running on some code that aims at chaos and destruction; and, were we instead in his place, we would seek a more sympathetic view. These issues are not simple ones, and the moral frameworks that surround our judgments are likely beyond our knowledge and perception. Yet, it is important to bring all our moral intuitions into scrutiny that we may analyze and hone them — perfecting the useful and dropping away the bad. After all, we too need to know what we value and work towards with our lives: whether we take the path of the Sheikah, or that of the Yiga. Few things are more important.

Notes and Works Cited:

[1] One need look no further than Purah, Symin, or Robbie at work in the Ancient Tech Labs for evidence of this. (Though, of course, I am not saying that every Sheikah has this scientific bent toward discovery and progress — merely that the Sheikah seem predisposed to this at a rate unfound in other Hylian peoples.)

[2] We learn of this murder from Dorian, who serves as one of the gatekeepers to Impa’s house in Kakariko Village. In the past, he had fallen in love with a Sheikah woman of the village during a period of prolonged reconnaissance for the Yiga. Dorian and his wife eventually had two children, and his love and new family led him to betray his erstwhile clan. Out of vengeance, the Yiga killed his wife and continued to blackmail him long after her murder. As he relates to Link: “My wife . . . the mother of my children . . . she was killed by the Yiga Clan. That is why Koko now acts as Cottle's mother.”

[3] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, pp. 326-7. Dark Horse Books, a Division of Dark Horse Comics, Inc., 2018.

[4] It took several hours to find a headpiece similar to those worn by these Gerudo statues, and I still feel as though there may be closer designs. If you are knowledgeable about such things and happen to recognize them, please contact me.

[1] One need look no further than Purah, Symin, or Robbie at work in the Ancient Tech Labs for evidence of this. (Though, of course, I am not saying that every Sheikah has this scientific bent toward discovery and progress — merely that the Sheikah seem predisposed to this at a rate unfound in other Hylian peoples.)

[2] We learn of this murder from Dorian, who serves as one of the gatekeepers to Impa’s house in Kakariko Village. In the past, he had fallen in love with a Sheikah woman of the village during a period of prolonged reconnaissance for the Yiga. Dorian and his wife eventually had two children, and his love and new family led him to betray his erstwhile clan. Out of vengeance, the Yiga killed his wife and continued to blackmail him long after her murder. As he relates to Link: “My wife . . . the mother of my children . . . she was killed by the Yiga Clan. That is why Koko now acts as Cottle's mother.”

[3] White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, pp. 326-7. Dark Horse Books, a Division of Dark Horse Comics, Inc., 2018.

[4] It took several hours to find a headpiece similar to those worn by these Gerudo statues, and I still feel as though there may be closer designs. If you are knowledgeable about such things and happen to recognize them, please contact me.