Zora's Domain

With help and inspiration from Clara, who so appropriately termed this “Zora Nouveau”.

"The domain is one giant sculpture, a feat of architecture that has drawn admirers from the world over. Our great domain will ever stand as a hallmark of the esteemed artists who made it, an eternal symbol of Zora pride."

— King Dorephan, Breath of the Wild

"The domain is one giant sculpture, a feat of architecture that has drawn admirers from the world over. Our great domain will ever stand as a hallmark of the esteemed artists who made it, an eternal symbol of Zora pride."

— King Dorephan, Breath of the Wild

Near the mouth of the Zora River is a signpost. The forking road which breaks around it branches north and east, the left path leading to “the maw of death mountain”, and the right to Zora’s Domain. And while Breath of the Wild is fraught with choices that the player must make, both practical and moral, there is likely no greater aesthetic choice to be found anywhere in the game, or perhaps anywhere in the series as a whole. This is a dramatic statement, I realize, but I believe it is also true. At the end of each path are peoples with starkly differing views on beauty, art, and architecture, and, happily, today we are taking the eastern road — to Zora’s Domain.

The trail which strays off to the right from the larger roads of Hyrule is itself a simple one, winding and circuitous, ranging far and wide before it finally brings one to Zora’s Domain. As in Middle-earth, wherein Bag End is itself obliquely connected to Barad-dûr, Tolkien’s quote about roads is, as it always is, felicitous: “He used often to say there was only one Road; that it was like a great river: its springs were at every doorstep, and every path was its tributary. 'It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out of your door,' he used to say. 'You step into the Road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there is no knowing where you might be swept off to.'” Likewise, in this incarnation of Hyrule, there is almost nowhere you cannot get via road.

The trail which strays off to the right from the larger roads of Hyrule is itself a simple one, winding and circuitous, ranging far and wide before it finally brings one to Zora’s Domain. As in Middle-earth, wherein Bag End is itself obliquely connected to Barad-dûr, Tolkien’s quote about roads is, as it always is, felicitous: “He used often to say there was only one Road; that it was like a great river: its springs were at every doorstep, and every path was its tributary. 'It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out of your door,' he used to say. 'You step into the Road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there is no knowing where you might be swept off to.'” Likewise, in this incarnation of Hyrule, there is almost nowhere you cannot get via road.

This dirt trail leading to the Domain climbs hills and descends into valleys, even tracing its way up mountainous cliffs, all in pursuit of its goal. And it seems to be made to highlight certain features of Lanayru Province: in particular its unique stone, which we eventually determine is luminous stone, used in both armor and architecture. As we walk slowly through the vales leading to the city, the stone shimmers lambently in the light or sits damply glistening in the rain; and the weather is rather temperamental here, affording rain often, keeping the fountains of Hyrule ever full. Pine trees predominate in this area, but there are also strange plants which are seen nowhere else in the world — coral- and seaweed-like vegetation in soft shades of purple and pink. Thus the footpath sways to and fro across the land, already teaching us something about the Zora culture: that perhaps it is more important to tread slowly and take in the world than it is to treat it as simply an obstacle between origin and destination.

Every so often we stumble (sometimes literally so) across one of the raw natural bridges which serve to connect one shore of the river to the other — they are no more than fallen rocks! There is no binding agent between the stones, nor any guardrail, nor any decorative element. As we will soon discover, the Zora are not incapable of architectural glory, and they have clear skill in building bridges, so why have these crossings been left as they are? Like a child bent on getting to her destination, we end up with a roughtrod path and foot-stones to make our crossing. What can we make of this other than a deep love of the natural, or at least a (perhaps humorous) respect for the ways of stock and stone? These paths put us in direct contact with the natural order; they slow us, forcing perception and attention into the ground directly beneath our feet. And why does the path wind as it does, through channels in the rock, and along and over the cliffs? Given the architectural skill of the Zora, and the capacity for engineering of their Hylian allies, why not a more linear approach? Two answers seem to appear when this question is asked. One is that it is a method of defense, of slowing and waylaying the enemy, and the other is that it simply highlights the terrain and forces wayfarers to become accustomed to the raw natural beauty of this province.

Every so often we stumble (sometimes literally so) across one of the raw natural bridges which serve to connect one shore of the river to the other — they are no more than fallen rocks! There is no binding agent between the stones, nor any guardrail, nor any decorative element. As we will soon discover, the Zora are not incapable of architectural glory, and they have clear skill in building bridges, so why have these crossings been left as they are? Like a child bent on getting to her destination, we end up with a roughtrod path and foot-stones to make our crossing. What can we make of this other than a deep love of the natural, or at least a (perhaps humorous) respect for the ways of stock and stone? These paths put us in direct contact with the natural order; they slow us, forcing perception and attention into the ground directly beneath our feet. And why does the path wind as it does, through channels in the rock, and along and over the cliffs? Given the architectural skill of the Zora, and the capacity for engineering of their Hylian allies, why not a more linear approach? Two answers seem to appear when this question is asked. One is that it is a method of defense, of slowing and waylaying the enemy, and the other is that it simply highlights the terrain and forces wayfarers to become accustomed to the raw natural beauty of this province.

Because the Zora have dwelt here for ten-thousand years, their ties to the land obviously run deep. Unlike humans, which are adaptable to almost any setting, the Zora require a great deal of clean water, which made certain demands on the setting of their civilization. Finding an abundance of running water and a truly unique stone in this region, they managed to capture the essences of both of these materials in their architecture — and this is immediately visible in the first structure we see: Inogo Bridge.

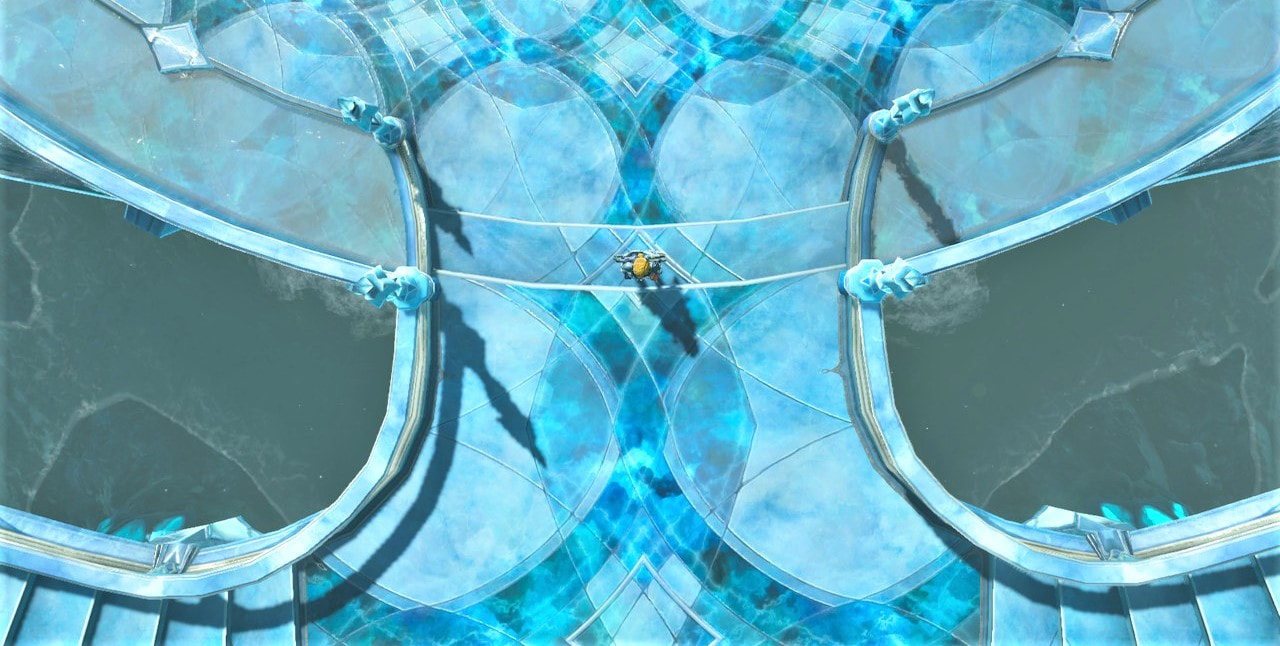

Although much will be discussed about the artistic tradition of the Zora and its real-world influences below, we need to first focus the eye and mind a bit before moving on. A couple things should be immediately accessible from an initial impression: the color scheme, the materials, and the forms. Two unmanned turrets, like spears thrusting out of the ground, flank the entrance of the bridge, and, like all mature architectural styles, they serve as microcosms for those things of which they are actually just a part. These watchtowers rise up, pagoda-like, built of striation and strata, each bearing a different design; some are simply carved, while others are covered with metal filigree, which creates an elegant silver latticework that complements perfectly the myriad blues of the towers. As to the stones at the heart of this creation, they are all utterly and exceptionally blue: an iridescent panoply of blues, a triumphant fanfare of the element of the Zora, all ceruleans and ultramarines set against turquoise and cornflower and lapis. If the shallows of the ocean are called to mind, or running stream-water over dappled river-stones beneath, then the aim has been achieved. To commune deeply with these colors, one need only walk across the bridge on a well-lit day; looking underfoot, one can see light that, as it scatters in inimitable reflections and refractions, gives the very appearance of the submarine — or like a mirrored pond which captures the clouds passing quickly overhead.

Although much will be discussed about the artistic tradition of the Zora and its real-world influences below, we need to first focus the eye and mind a bit before moving on. A couple things should be immediately accessible from an initial impression: the color scheme, the materials, and the forms. Two unmanned turrets, like spears thrusting out of the ground, flank the entrance of the bridge, and, like all mature architectural styles, they serve as microcosms for those things of which they are actually just a part. These watchtowers rise up, pagoda-like, built of striation and strata, each bearing a different design; some are simply carved, while others are covered with metal filigree, which creates an elegant silver latticework that complements perfectly the myriad blues of the towers. As to the stones at the heart of this creation, they are all utterly and exceptionally blue: an iridescent panoply of blues, a triumphant fanfare of the element of the Zora, all ceruleans and ultramarines set against turquoise and cornflower and lapis. If the shallows of the ocean are called to mind, or running stream-water over dappled river-stones beneath, then the aim has been achieved. To commune deeply with these colors, one need only walk across the bridge on a well-lit day; looking underfoot, one can see light that, as it scatters in inimitable reflections and refractions, gives the very appearance of the submarine — or like a mirrored pond which captures the clouds passing quickly overhead.

While this is not Inogo Bridge, it captures the same bright essence of Zora stonework

Pockets of native stone in Lanayru are naturally luminous, and have been used in conjunction with a duller blue stone to create panels along the bridge which take the form of flowers and other plants. There is a grace and an elegance to these designs, to be sure, but also a sharpness that borders on violence (for, of course, the Zora are not strangers to war, though they are infrequently troubled by it). This initial area encapsulates the twin architectural effects of all Zora architecture: grace of line and form in conjunction with a projection of martial strength. And this just goes to show that might and beauty are not always opposed to one another: things that are beautiful can still appear bellicose, and even things that are warlike can be wonderful. Indeed, everything along the path leading to Zora’s Domain has an element of the martial about it: the signs have, for their base, an almost mace-like design, while the signs themselves are like the foreshortened blades of swords. The lampposts that light the way, like the turrets, are tipped spears jutting from the earth. Their light-sources (likely derived from luminous stone) sit atop a highly-structured hierarchy of rock. They are many-levelled and complex — far from a simple torch or plain pole. Other lamps mark certain points along the path, though these are more like little trees than pikes; their trunks are lit up in white-blue light and their tops open up in leaves, perhaps in reference to the palm and papyrus capitals of Egyptian architecture. These lamps are altogether more comforting in appearance, though they are fewer in number.

The final thing that we encounter along this path, drawing ever closer to our destination, is a large and illuminated inscription set into the cliffside. There are many of these scattered about the valley ahead, and one of the first gives a brief glimpse into the foundations of Zora civilization:

“Once every 10 years, the Lanayru region experiences unusually heavy rainfall. The Zora River flooded every time. The tides damaged not only our domain but our people, washing away poor souls and causing great suffering and disarray. The Zora king of that time, after seeking aid from the king of Hyrule, rode out to see what could be done. By joining the architectural genius of the Zora and Hyrule's technological prowess, East Reservoir Lake was swiftly built. Thanks to this fruitful partnership, Hyrule was no longer plagued by these devastating floods. In gratitude, the Zora king promised the King of Hyrule to manage the reservoir level to protect all of Hyrule from floods. Each Zora king since has kept that oath, spanning 10,000 years. That is why the reservoir signifies our bond with Hyrule.”

The ground, then, from which this people sprang, was inextricably tied to their learning to control the floodwaters that plagued Hyrule. Sealing the waters away through engineering and architecture, two disparate cultures formed a bond that lasted millennia, and which extends even after the Calamity of a century ago. And there is something to this flood motif. The developers, in choosing the backdrop of the Flood as the basis of a founding mythology, were tapping into something deeply existential within world mythology, something that comes to us from the reaches of the human past.

Flood myths exist the world over, reaching from Mesoamerica to Mesopotamia, and while the Biblical Flood is perhaps the most well-known, it likely borrowed from more antique sources — the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh and its counterpart, the Akkadian Atrahasis Epic, which were both composed circa 1800 BCE. [1] One can easily see the major parallels between the account of the Flood in Genesis and the Eridu Genesis simply from their most basic plot elements, though there are, of course, differences both cultural and moral. [2] Scholars have given no short shrift to the potential historicity of such floods, though all modern scientific understandings preclude a truly global flood event. Yet regional flooding remains a likely background for such myths, and scholars posit outburst floods (rare floods of extreme magnitude), among other things, as reasoning for these stories; other potential explanations relate to the incautious damming of rivers, sweeping tsunamis, massive rainfall, and melting glaciers. Other interesting theories have stated that some (later) flood myths actually came about due to ancient peoples observing marine fossils and seashells in areas far removed from the coast. To wit, they creates myths which fit the evidence. [3]

These are all literalist accounts of mythical narratives, but there is still the symbolic to consider, and by far the most delightful — and intriguing — theories of origination come to us from the psychoanalysts. Géza Róheim’s The Flood Myth as Vesical Dream begins: “Flood myths frequently represent the flood as urine, thereby revealing their dream origin.” (As ridiculous as such an essay sounds to modern ears, it is actually a rather fascinating article.) Alan Dundes’s The Flood as Male Myth of Creation works off the propositions that the deity-human relationship is in fact the parent-child relationship, and that all men at heart envy “female parturition”, i.e. childbirth. Because males cannot produce life, this desire obscurely manifests in flood mythology; Dundes argues that this is “because a flood constitutes a cosmogonic projection of the standard means by which every child-bearing female creates.” These stories are “modeled after the female flood, the release of amniotic fluids. As the individual is created or brought forth by females, so the world is created or ‘re-created’ by males.” [4] We can also view, more broadly, the creation myth as the desire for humanity to be cleansed and reborn, and as a symbol of human tenacity and the desire to live. This last lens brings us to an important aspect of the Great Flood myth: the Flood Hero.

These are all literalist accounts of mythical narratives, but there is still the symbolic to consider, and by far the most delightful — and intriguing — theories of origination come to us from the psychoanalysts. Géza Róheim’s The Flood Myth as Vesical Dream begins: “Flood myths frequently represent the flood as urine, thereby revealing their dream origin.” (As ridiculous as such an essay sounds to modern ears, it is actually a rather fascinating article.) Alan Dundes’s The Flood as Male Myth of Creation works off the propositions that the deity-human relationship is in fact the parent-child relationship, and that all men at heart envy “female parturition”, i.e. childbirth. Because males cannot produce life, this desire obscurely manifests in flood mythology; Dundes argues that this is “because a flood constitutes a cosmogonic projection of the standard means by which every child-bearing female creates.” These stories are “modeled after the female flood, the release of amniotic fluids. As the individual is created or brought forth by females, so the world is created or ‘re-created’ by males.” [4] We can also view, more broadly, the creation myth as the desire for humanity to be cleansed and reborn, and as a symbol of human tenacity and the desire to live. This last lens brings us to an important aspect of the Great Flood myth: the Flood Hero.

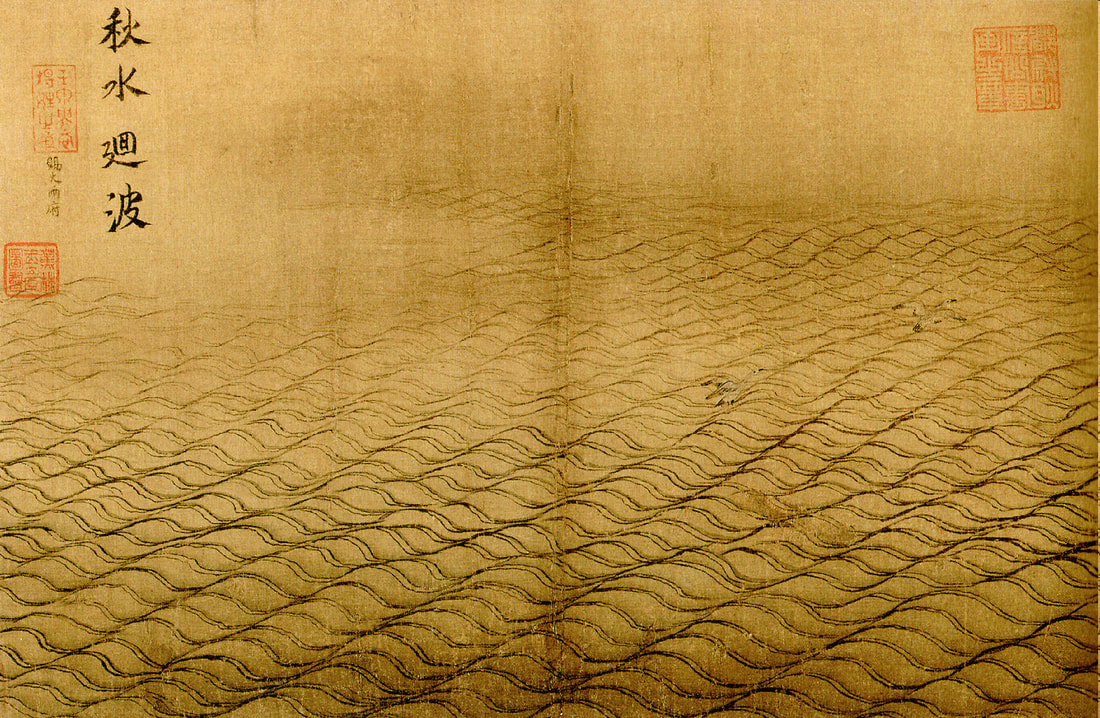

Above: The Waving Surface of the Autumn Flood by Ma Yuan (1160–1225)

The Flood Hero is simply he (for it is usually a male at center, though his family may also be present in the telling) who, chosen by divinity, survives the destruction of earth — the Hebrew Noah, the Sumerian Ziusudra, the Menominee’s Manabozho, and the Greek Deucalion. But another, rather different, flood mythology comes to us out of China, in which the Flood Hero does not merely survive, but actually learns to control the flood. China as a civilization is undeniably tied to its major rivers, the Yangzi and the Yellow, which both have a history of terrible flooding. If we imagine that there are any literal accounts for the origination of flood myths, the frequent and devastating floods of these rivers may account for the fact that “from all mythological themes in ancient Chinese, the earliest and so far most pervasive is about flood.” [5] And while there are several distinct threads in Chinese flood mythology, our purposes here focus on tales in which the Flood Hero needs to learn to control the encroaching waters. Among these scattered myths and fragments, “the Gun-Yu myth is the most representative one in the sense that it intensively stresses how the flood eventually is controlled by the great efforts from two generations.” [6] This is obviously different from myths which solely praise the survival of the Flood Hero; in some Chinese myths, one need not only survive, but make the world livable for others. [7] In other words, it is the birth of human civilization through the regulation of nature, just as with the Zora.

The story as it is told centers around four men — Yao and Shun, who came to rule jointly, and Gun and Yu, who were in charge of controlling the flood: a pair to reign and a pair to regulate. The historicity of these events is slightly in question, as the dates of Yu’s reign predate the oldest-known writings in Chinese history by about one-thousand years. So, as always, we take our history with a bit of salt. The story goes something like this:

Yao was a remarkable and respected king, being of upright character and just leadership. The beginning of his reign was marked by much progress, and perhaps would have been praised as a period of unending peace and development had it not been for the Great Flood which descended upon his land. It was a flood which lasted longer than a generation, displacing great swathes of the empire’s population, causing famine and death on an unbelievable scale. “. . . Yao himself was said in the canon to have described it thus: ‘Like endless boiling water, the flood is pouring forth destruction. Boundless and overwhelming, it overtops hills and mountains. Rising and ever rising, it threatens the very heavens.’” [8] With the rising waters, the shape of the very land was changed before its citizens’ eyes, and with lines of communication and transportation now severed, Yao was beset by not only the greatest flood in memory, but by societal fragmentation and the potential collapse of his empire. He sought to find someone to quell the floodwaters, eventually putting Gun (a distant relative) in charge of controlling the chaos.

The story as it is told centers around four men — Yao and Shun, who came to rule jointly, and Gun and Yu, who were in charge of controlling the flood: a pair to reign and a pair to regulate. The historicity of these events is slightly in question, as the dates of Yu’s reign predate the oldest-known writings in Chinese history by about one-thousand years. So, as always, we take our history with a bit of salt. The story goes something like this:

Yao was a remarkable and respected king, being of upright character and just leadership. The beginning of his reign was marked by much progress, and perhaps would have been praised as a period of unending peace and development had it not been for the Great Flood which descended upon his land. It was a flood which lasted longer than a generation, displacing great swathes of the empire’s population, causing famine and death on an unbelievable scale. “. . . Yao himself was said in the canon to have described it thus: ‘Like endless boiling water, the flood is pouring forth destruction. Boundless and overwhelming, it overtops hills and mountains. Rising and ever rising, it threatens the very heavens.’” [8] With the rising waters, the shape of the very land was changed before its citizens’ eyes, and with lines of communication and transportation now severed, Yao was beset by not only the greatest flood in memory, but by societal fragmentation and the potential collapse of his empire. He sought to find someone to quell the floodwaters, eventually putting Gun (a distant relative) in charge of controlling the chaos.

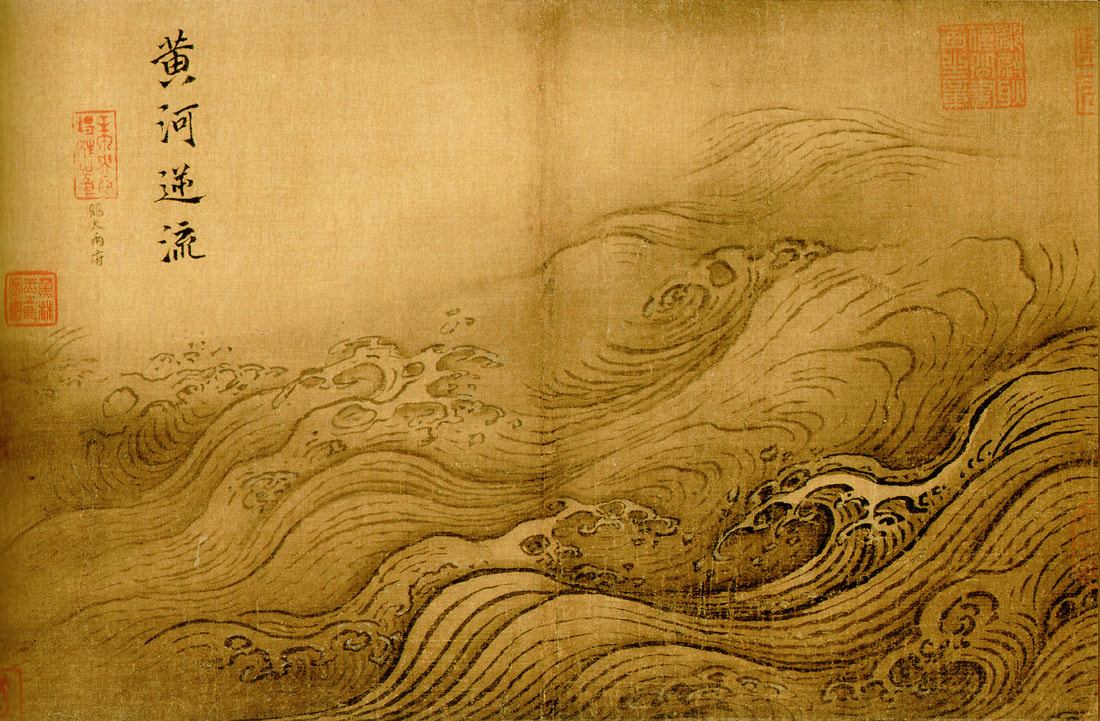

Above: The Yellow River Breaches its Course by Ma Yuan (1160–1225)

Some of the more fantastic versions of this tale tell how Gun stole xirang (息壤 — "living soil") from the supreme god, which continually expanded under certain conditions, though whenever he would apply it to barricade the flood waters, his efforts would fail. The more materialistic accounts track his attempts to build measures against the floodwaters. In all versions, however, even after nine years, the flood continued, and society was imploding. Emperor Yao wanted to abdicate, but his advisers refused, instead offering Shun (another distant relative) as an alternative. After a rather byzantine testing period of three years (in subjects from Confucian administration and philosophical mastery, to his marital choices and survivalist training), Shun became co-emperor. Shun had then to deal with the flood, and after he reorganized the empire — restructuring the calendar, winning over various lords, standardizing scales and measurements, and reformulating parts of the penal code — he came to his most important task: figuring out what to do with Gun, who had not yet checked the floodwaters after thirteen years. Gun continually failed to achieve success with his projects, maintaining that even though “his dikes failed amongst one and all . . . he insisted that there was nothing wrong with his policy; the trouble was that the dikes had not been built high enough. So he kept on demanding that the people build more dikes, higher dikes.” [9] With increased pressure on Gun to succeed from the new co-emperor, he began decrying his new overlord for his commoner upbringing. As this was not behavior to be directed at an emperor, and in light of Gun’s persistent failures, Shun decided that he should be exiled to far-off Feather Mountain, a mountain out of Chinese mythology. (And his was not a happy end [10]).

With Gun gone, Yu, his son, was put in charge, and through changing strategies from containment to drainage — channeling the waters into a system of irrigation canals instead of simply trying to stop them by damming — he was able to make progress toward saving the empire. He also instituted policies concerning the frequent dredging of riverbeds and he worked to fashion other outlets for rivers into the sea. [11] Some of these channels and waterways were constructed with the help of dragons and giant tortoises, and he was even assisted by Hebo, the god of the Yellow River, who provided him with a map of the river and its surrounding area. [12] Yu worked hard, never taking time to visit his wife and children, and is said to have slept only among the commoners, becoming covered in callouses from his industry. He eventually succeeded in taming the Great Flood, and he assisted Emperor Shun in reorganizing the Middle Kingdom, safeguarding its agriculture and industry, as well as the unifying its many peoples. His perseverance and intelligence helped him to achieve the support and respect of the populace, and he was eventually recognized as the only person capable of claiming the throne. Shun saw this as well, and offered him the throne even above his own son; but Yu demurred, casting doubts upon his own virtue. Yet the other lords were finally able to convince him to ascend to power, and in passing the Dragon Throne to his son, he founded China’s first dynasty: the Xia, which ruled from ca. 2070 to ca. 1600 BCE.

Stretching back even farther than the Xia Dynasty is the kingdom founded by the Zora: a domain established 10,000 years in the past, when the Zora, searching for a land marked by pure and plentiful water, discovered Lanayru. Both the Rutala and Zora Rivers have their sources here, and all of Hyrule’s fresh water comes from the Lanayru Great Spring. [13] With the reservoir completed thanks to the partnership between the Hylians and the Zora, the floods, which before had wreaked civilizational havoc, were eventually put to rest. Now positioned at the mother of all waters, they took upon themselves the task of managing the water resources of all Hyrule; they oversee the reservoir levels constantly, and have monitors who report to the king when the levels near capacity. [14] In addition to water, they found that their land “was also rich in ore”, which led to “a unique form of stonemasonry” that created for the Zora an ethereal architectural sculpture to call home. [15] And like dynastic China, their royal family “goes back countless generations and unifies the people.” [16] Among a citizenry which ages far more slowly in comparison to the other races of Hyrule, we can imagine that their historical memory far surpasses that of the shorter-lived races. For this reason, among many others, we see the Zora carving their history into stone, placing it around their domain as a symbol of edification and achievement; these monuments are crystallizations of the history and mythology of the Zora, who seem to have the largest extant body of stories in Hyrule, extending from tales of the ancient sages to the recent defeats of monsters disrupting the land’s harmony. [17]

With Gun gone, Yu, his son, was put in charge, and through changing strategies from containment to drainage — channeling the waters into a system of irrigation canals instead of simply trying to stop them by damming — he was able to make progress toward saving the empire. He also instituted policies concerning the frequent dredging of riverbeds and he worked to fashion other outlets for rivers into the sea. [11] Some of these channels and waterways were constructed with the help of dragons and giant tortoises, and he was even assisted by Hebo, the god of the Yellow River, who provided him with a map of the river and its surrounding area. [12] Yu worked hard, never taking time to visit his wife and children, and is said to have slept only among the commoners, becoming covered in callouses from his industry. He eventually succeeded in taming the Great Flood, and he assisted Emperor Shun in reorganizing the Middle Kingdom, safeguarding its agriculture and industry, as well as the unifying its many peoples. His perseverance and intelligence helped him to achieve the support and respect of the populace, and he was eventually recognized as the only person capable of claiming the throne. Shun saw this as well, and offered him the throne even above his own son; but Yu demurred, casting doubts upon his own virtue. Yet the other lords were finally able to convince him to ascend to power, and in passing the Dragon Throne to his son, he founded China’s first dynasty: the Xia, which ruled from ca. 2070 to ca. 1600 BCE.

Stretching back even farther than the Xia Dynasty is the kingdom founded by the Zora: a domain established 10,000 years in the past, when the Zora, searching for a land marked by pure and plentiful water, discovered Lanayru. Both the Rutala and Zora Rivers have their sources here, and all of Hyrule’s fresh water comes from the Lanayru Great Spring. [13] With the reservoir completed thanks to the partnership between the Hylians and the Zora, the floods, which before had wreaked civilizational havoc, were eventually put to rest. Now positioned at the mother of all waters, they took upon themselves the task of managing the water resources of all Hyrule; they oversee the reservoir levels constantly, and have monitors who report to the king when the levels near capacity. [14] In addition to water, they found that their land “was also rich in ore”, which led to “a unique form of stonemasonry” that created for the Zora an ethereal architectural sculpture to call home. [15] And like dynastic China, their royal family “goes back countless generations and unifies the people.” [16] Among a citizenry which ages far more slowly in comparison to the other races of Hyrule, we can imagine that their historical memory far surpasses that of the shorter-lived races. For this reason, among many others, we see the Zora carving their history into stone, placing it around their domain as a symbol of edification and achievement; these monuments are crystallizations of the history and mythology of the Zora, who seem to have the largest extant body of stories in Hyrule, extending from tales of the ancient sages to the recent defeats of monsters disrupting the land’s harmony. [17]

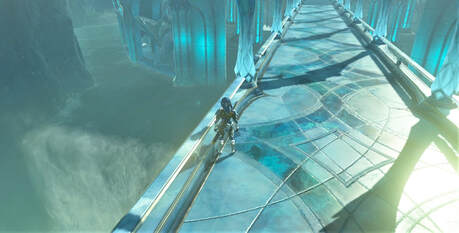

Once again rejoining the path, though Link will come to many such inscriptions on his journey to the Zora lands, we see that several other bridges cut through the sky, leaping from one hill to another, each with unique balustrades, patterning, and support. These bridges were perhaps built at different times, or by different craftspeople, though they are all tightly linked in the same architectural tradition. Most impressive of all of them, of course, is the Great Zora Bridge, which is not bolstered by a single support from below — there is not a single pier, column, or buttress. It simply floats on the strength of its own materials and engineering, showcasing the height of accomplishment of the civilization that constructed it. And as we cross the frontmost gate — its topmost element proudly bearing the symbol of the Zora: three outward-facing crescents — in that exact moment we hear a familiar music cascading down through the air, and, indeed, down through the ages.

The bridge is marked with ceremonial gateways, slightly redolent of the Senbon Torii that marks the Fushimi Inari-Taisha shrine in Kyoto. And what a sight at the other end of the bridge. In the designers’ description, “Zora’s Domain features a massive fish-shaped monument at its heart. Water bubbles up below it and runs through the village via beautifully crafted waterways. The settlement is a sight to behold, appearing to have been carved from a single stone.” [18] While that last statement seems a touch fanciful, there is no doubt that the settlement is truly something to write home about, and that the channels of cool water are certainly at the heart of its design. The flowing water of the Domain is reflected in the cascades surrounding it in the valley, most of which have been engineered by the Zora to help control the flow of water into Hyrule. Around the city there are seven dams which form lakes and smaller bodies of water, from the massive East Reservoir Lake to the more diminutive Toto Lake, which flows also into Akkala, eventually emptying into the lake which rests below Tarrey Town. Zora River is formed from the water of these seven dams, beginning in a broad basin below Zora’s Domain and eventually emptying into the Lanayru Wetlands where we initially took up our path. Other important locations outside the city are the Veiled Falls, where a shrine trial awaits Link, and Shatterback Point, a promontory over the reservoir from which Zora warriors test their mettle by diving at great risk to their lives. [19] But the focus is always upon the Domain itself, which in the sunlight is dappled and bright, and at night glows brilliantly from the rock itself.

The bridge is marked with ceremonial gateways, slightly redolent of the Senbon Torii that marks the Fushimi Inari-Taisha shrine in Kyoto. And what a sight at the other end of the bridge. In the designers’ description, “Zora’s Domain features a massive fish-shaped monument at its heart. Water bubbles up below it and runs through the village via beautifully crafted waterways. The settlement is a sight to behold, appearing to have been carved from a single stone.” [18] While that last statement seems a touch fanciful, there is no doubt that the settlement is truly something to write home about, and that the channels of cool water are certainly at the heart of its design. The flowing water of the Domain is reflected in the cascades surrounding it in the valley, most of which have been engineered by the Zora to help control the flow of water into Hyrule. Around the city there are seven dams which form lakes and smaller bodies of water, from the massive East Reservoir Lake to the more diminutive Toto Lake, which flows also into Akkala, eventually emptying into the lake which rests below Tarrey Town. Zora River is formed from the water of these seven dams, beginning in a broad basin below Zora’s Domain and eventually emptying into the Lanayru Wetlands where we initially took up our path. Other important locations outside the city are the Veiled Falls, where a shrine trial awaits Link, and Shatterback Point, a promontory over the reservoir from which Zora warriors test their mettle by diving at great risk to their lives. [19] But the focus is always upon the Domain itself, which in the sunlight is dappled and bright, and at night glows brilliantly from the rock itself.

When Link arrives in the region, he is quickly brought before King Dorephan, who remembers Link fondly, yet with a lingering regret. Link, for many of the Zora, we come to find, is a bittersweet memory of the events a century ago which claimed the life of Princess Mipha. Though reluctantly, the king allowed her to ascend to her role when Princess Zelda hand-selected her to become a Champion of Hyrule; trapped in the Divine Beast Vah Ruta, she died alone to an aspect of Calamity Ganon. Though Link remembers little of this, he is still held somewhat responsible for her death: for partly out of Mipha’s love for Link did she die. Muzu, council-member and advisor to Dorephan, encapsulates these complex feelings best of all; he served as Mipha’s primary tutor during her childhood and adolescence, and when she was lost, he came to hate all Hylians. Indeed, many Zora lost faith in their longtime allies at the princess’s death, and it wasn’t until Prince Sidon, against the Zora leadership, went to ask for Hylian aid in quelling Vah Ruta that this grudge was finally laid to rest. But other than this recent chaos, the Zora were remarkably safe from the Calamity. Like the Gerudo, their relative isolation and the defensive nature of their surroundings protected them against the Calamity which destroyed their Hylian allies. Only one Guardian ever happened upon their city, whereupon it was swiftly dispatched by King Dorephan himself. So while the Zora indeed lost their beloved princess, it seems only appropriate that we keep some sense of proportion in the true devastation of the Great Calamity.

The main plaza of the Domain, with Mipha's statue seen at right with the Lightscale Trident

Approaching this haven from across the main bridge, a few things immediately spring up in the mind concerning its architecture: it is intensely symmetrical with a beautiful, holy geometry, there is a critical integration of water within the architectural setting, and nothing — from the inn to the throne room — is cut off from the elements. And above the entire Domain rises a gargantuan fish modelled after the guardian deity of the Zora. The designers took great care in creating Zora’s Domain, so I will give the full Creating a Champion description here:

“I decided on the direction for Zora's Domain based on the Zora’s faith in Lord Jabu-Jabu from past games. The concept is that their faith has persisted into the present and manifests itself through their architecture. That led to the giant fish statue and the temple-like appearance of Zora’s Domain. There wasn’t as much water flowing through the village in the initial designs, but we realized that the Zora would most likely be happiest in the water, so we filled the village with it. From there, the Zora’s traits and lifestyle fell into place. They are merpeople who live in a village, and the design of Zora’s Domain needed to express that, which led to the current appearance and facilities found there. The reason that the Zora record their history on stone monuments is that paper books would get wet and fall apart right away. It’s a simple idea, but I took great care to ensure that props placed there would not seem out of place, not only in Zora’s Domain but also for the players visiting it.” [20]

Looking around, we do feel as though we have entered onto the grounds of a temple: the graceful, curvilinear stonework, the open-air pavilions, the stone itself casting light. There is a deep sense of the holy here, as the Zora have sought to reify their philosophy in their very dwelling. [21] Walking around the Domain, we get a sense that the Zora are truly quite different due to their longevity — perhaps more high-minded: they seem to be at least as concerned with history, tradition, and lore as they are with the more earthly topics of relationships or business. But this is not to say that they are a bunch of effete navel-gazers; they are still a lively and industrious people, constantly honing their crafts and trades. One of the first Zora we meet is hard at work repairing a column with luminous stone, and not far off are the general store and blacksmith. This workshop has myriad tools, which speaks to a dedication to trade and detail largely unparalleled in Hyrule; there are various sizes of pliers, magnifying lenses, hammers, chisels, and even a hand-powered drill. And these artisan skills extend even to the royals; each Zora Princess bequeaths a set of hand-crafted armor to their betrothed, in accordance with ancient tradition. Everywhere we see incredibly fine examples of armor, weaponry, and jewelry. The Zora are inarguably the finest metalsmiths in Hyrule, and each Zora wears their individual treasured pieces. The children, it is said, wear adult-sized jewelry from youth that they eventually grow into as they age. [22] And this is all uncannily fitting, as in order to understand Zora architecture, we must turn eventually to the decorative arts: specifically jewelry and metalworking. Zora jewelry (much like their architecture) is distinctive in its fanciful lines and graceful form, and relies upon skilled tradespeople — not machinery and uncouth industrialism — for its creation. With all this held in mind, then, we can finally turn to its real-world influences.

The workshop of the smithy Dento, who crafted the Lightscale Trident as a gift for Mipha upon her birth

In order to fully appreciate the departure of architectural schools like Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau from the standard practice of the mid-to-late nineteenth century, we should take a brief look at the state of architecture at that time. And, to my mind, no one captures this like E.H. Gombrich in his quirky-yet-scholarly The Story of Art. He writes: “Superficially, the end of the nineteenth century was a period of great prosperity and even complacency. But the artists and writers who felt themselves outsiders were increasingly dissatisfied with the aims and methods of the art that pleased the public. Architecture provided the easiest target for their attacks. Building had developed into an empty routine. We remember how the large blocks of flats, factories and public buildings of the vastly expanding cities were erected in a motley of styles which lacked any relation to the purpose of the buildings. Often it seemed as if the engineers had first erected a structure to suit the natural requirements of the building, and a bit of ‘Art’ had then been pasted on the facade in the form of ornament taken from one of the pattern books on ‘historical styles’. It is strange how long the majority of architects were satisfied with this procedure. . . . [but] critics and artists were unhappy about the general decline in craftsmanship caused by the Industrial Revolution, and hated the very sight of these cheap and tawdry machine-made imitations of ornament which had once had a meaning and a nobility of its own.” [23]

Against this backdrop — of drab buildings constructed without feeling or inspiration — two movements arose: the Arts and Crafts movement and, slightly after that, L’Art Nouveau. William Morris, greatly inspired by the writings of John Ruskin, was perhaps the biggest player in the Arts and Crafts movement; he wished for a return to the artisanry and spirit of medieval craftsmanship in the face of the pitiless onslaught of industry into the arts. Morris’s firm did important work in many of the decorative arts, from wallpaper and textiles to stained-glass windows, in everything attempting to popularize the movement and create beautiful items for daily use that were produced by honest craftspeople. Arts and Crafts architecture drew greatly from English vernacular architecture with its natural settings and bucolic charms. It needn’t be said that this was largely a past-oriented movement — a return, in some form, to the way things were. Art Nouveau, which sprang into life after the Arts and Crafts movement (but which partially grew out of it), took a decidedly more future-oriented approach. New materials had made their way into the architectural vernacular (particularly iron and glass), so why not simply use these materials to create a novel ornamentation? Instead of spurning the devils of machinery and industrialization, why not make them one’s playthings? Obviously these two attitudes were starkly different from one another, and to give a bit of further contrast between the two, hold this image of Arts and Crafts design in your mind as we venture together through Art Nouveau: “. . . interiors should be painted white, furniture should be made of oak, and . . . there should be only one pure ornament in each room” [24]

Against this backdrop — of drab buildings constructed without feeling or inspiration — two movements arose: the Arts and Crafts movement and, slightly after that, L’Art Nouveau. William Morris, greatly inspired by the writings of John Ruskin, was perhaps the biggest player in the Arts and Crafts movement; he wished for a return to the artisanry and spirit of medieval craftsmanship in the face of the pitiless onslaught of industry into the arts. Morris’s firm did important work in many of the decorative arts, from wallpaper and textiles to stained-glass windows, in everything attempting to popularize the movement and create beautiful items for daily use that were produced by honest craftspeople. Arts and Crafts architecture drew greatly from English vernacular architecture with its natural settings and bucolic charms. It needn’t be said that this was largely a past-oriented movement — a return, in some form, to the way things were. Art Nouveau, which sprang into life after the Arts and Crafts movement (but which partially grew out of it), took a decidedly more future-oriented approach. New materials had made their way into the architectural vernacular (particularly iron and glass), so why not simply use these materials to create a novel ornamentation? Instead of spurning the devils of machinery and industrialization, why not make them one’s playthings? Obviously these two attitudes were starkly different from one another, and to give a bit of further contrast between the two, hold this image of Arts and Crafts design in your mind as we venture together through Art Nouveau: “. . . interiors should be painted white, furniture should be made of oak, and . . . there should be only one pure ornament in each room” [24]

|

The interior of Standen House, an Arts and Crafts dwelling designed by Philip Webb with interiors by William Morris

|

Stairway of the Art Nouveau Hôtel Tassel; image by Yelkrokoyade / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

|

The architectural movement that concerns us today was known by many names: Sezessionstil in Austria, Jugendstil in Germany, Modernismo in Spain, and Stile Floreale in Italy. To much of the rest of the world, it was simply known as Art Nouveau, having taken its name from a gallery in Paris called the Maison de l’Art Nouveau. Given impetus by this fierce turning away from past and present tastes, Art Nouveau set about precisely what should be obvious from its name: the creation of a new art. Along with this goal was the desire to “synthesize all the arts in a determined attempt to create art based on natural forms that could be mass-produced for a large audience.” Like members of the Arts and Crafts movement, many in the Art Nouveau movement realized the necessity of making their art available to society at large (though this would not stop some from hiring out their skills to the fantastically wealthy). Yet the direction in which the movement headed was far from the ideals of its parent school. While the Arts and Crafts movement focused largely on more uncomplicated and historied two-dimensional ornamentation, Art Nouveau went far afield for aspects of its inspiration, enshrining “the sinuous whiplash curve of Japanese print designs” next to the more home-grown “expressively patterned styles of van Gogh, Gauguin, and their Post-Impressionist and Symbolist contemporaries.” [25] What emerged from this marriage (though there are plenty of other mistresses of inspiration) was a movement famously marked by “sinuous designs supposedly derived from nature, with formalized representations of flowers supported on long intertwined stalks.” [26] The operative word in that sentence — supposedly — speaks to the fact that much Art Nouveau embellishment borders on the fey and otherworldly. It is nature made whimsy. These flower and plant forms undulate and twist, often at angles that are not normally found in nature but that appear elegant, graceful, or even rapturous. Because of these characteristics, Art Nouveau is largely an asymmetric school that is focused on the effect on the viewer. Through all of it, there is a flow which follows the linear elements of the ornamentation, and almost always other design elements are merely accessories to the impression of the unified whole.

|

Left: stained glass in the Hotel Mezzara in Paris; image by O.Taris / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

|

Along with larger architectural progress, in the same way glass, ceramics, and jewelry played key roles in the Art Nouveau story. Glassmakers, shying away from mechanical production, “began to create inventive studio and limited-edition pieces by hand, working with highly skilled designers and craftsmen.” [27] The fluid essence of glass was a boon for those inspired by Art Nouveau inventiveness, and gave a new medium through which to express the dynamism and exuberance of the movement. And when paired with metalware, these pieces border on the sublime. But in terms of inspiration for the architecture of the Zora, jewelry seems to be it. For many years, jewelry had been relegated to creating elaborate settings for diamonds and other expensive stones. Mirroring much of the rest of the movement, Art Nouveau jewelry turned away from meaningless showmanship and deracinated ostentation, instead moving toward “its use of semi-precious stones and unusual, inexpensive materials . . . [whose designers] sought inspiration in previously neglected materials, such as opals, silver, rich enamelling, moonstones, turquoise, ivory, horn, bone, mother-of-pearl, and frosted glass.” [28] Even from the listed materials we can already glean some Zora inspiration: opalescence, rich use of silver, shimmering moonstone. But Art Nouveau jewelry was not simply known for its uncommon materials; we must also look to its natural underpinnings and grace of line. Looking at the popular pieces at the time, we see that design often featured flowers, grains, insects, elements of the avian, and the female body. But throughout all of them, regardless of their natural inspiration, we see the sweeping line, the dynamism and interplay of the precious metals at work. [29] This same attitude toward line and movement is found everywhere in Zora’s Domain, and given the similarity of material as written about above, we see very evident bonds between these two artistic achievements.

The dams built in the surround of Zora’s Domain never fail to stop me in my tracks: the sheer mass of them — their scale and proportioning — is simply awe-inspiring. Their high ogival arches, plunging lines, pendant-like embellishments, and luminous setting all combine to form something that leaves one rather astonished. The most impressive dam is that which helps form East Reservoir Lake, where the Divine Beast has been running amok. It was created “in a joint effort by the Hyrulean and Zora royal families over ten thousand years ago”, and its stairs rise elegantly up to a pavilion with a bedroom for guests. [30] Like a waterside cabana, this small bedroom contains a small bar, stools, and glasses, and a beautiful dock just outside extends into the reservoir almost at the level of the water. Standing atop the dam, looking back, we are presented with another splendid view of the Domain itself. Indeed, it is hard to find a bad view of the city. From high above, the symmetry of the settlement is striking, and we see that it has been built in layers, both in elevation and radiating outward from the central plaza. A massive ringing “wall” stands on immense piers at the outer edge of the city, with no connecting paths to the inner sanctuary. Given its inaccessibility, we can suppose that it has defensive purposes, though it also simply serves to impress. This outer wall is built of two main stories: the upper battlements and the lower arcade, likely for support. The upper walkway consists of one unified pathway extending all the way around the settlement, though it is curiously not flat, having sunken panels at set distances. (This may have something to do with the collection of water for runoff.) The lower arcade is almost a sculptural setting of massive flowers forming high arches which frame the larger piers of the upper level. And even here the connection to jewelry is obvious, as both the piers themselves, as well as the keystones of the arches which brace them, bear devices like earrings and brooches. With almost no alteration, one could wear either of these settings from the ears or around the collar.

Two flowing, weaving watercourses like catfish whiskers descend the outside of the complex, crisscrossing the sky. Other, smaller channels carry water within the inner city, and everywhere can be heard the sound of water: tinkling, flowing, falling. Small walkways intersect, chase, or run parallel to these water-courses, and the entire effect is a beautiful concatenation of paths of stone in the air. If one abstracts the Domain slightly, or views it aerially, we see that it too could almost be worn as a pendant.

There are two main levels of the city and two semi-levels in between the two principal ones. The first, which centers around the main plaza, holds the inn and smithy, and is where most of the Zora spend their daylight hours. A staircase beyond the statue memorializing Mipha leads slightly downward into a cave-like chamber where, standing in a pool of water, resides a Sheikah shrine. The fact that this exists here, just below the Throne Room, is a testament to the trust that exists between the far-flung peoples of Hyrule. Directly above this shrine chamber, sandwiched between it and the Throne Room, are the night pools: three ponds in which the Zora sleep. Two guards stand watch here during the darkness, and glowing snails make their homes among the pools. The pools are communal, which explains why there are no individual homes to be found within the city — only an inn for travelers less accustomed to resting in water. The second level is reached via two grand staircases which spring up from the central plaza, and further stairs into the Throne Room follow on their heels.

This chamber, open to the elements through an arcade, is both a testament to Zora architecture and community. Raised benches hug the sides of the room, offering seating for likely the entire population of the Zora, and a petitioner’s platform rises slightly in front of the throne, emblazoned with their sacred symbol. A huge opalescent dome looks down upon the king, patterned after the shape of a whale’s tail. Water falls from all sides of the room, cascading downward to the pool of rivers underneath the Domain. Unlike in Gerudo Town, where control over the water was largely to signify power and divinity, here it is a symbol of generosity and plenty. The king sits ensconced at the fountainhead of Hyrule, the very manifestation of bounteousness and nobility — he who freely gives life to the land. And surrounding him is a city as fluid, stunning, and as vital as the element to which it is bound: a necklace over the heart of the world.

There are two main levels of the city and two semi-levels in between the two principal ones. The first, which centers around the main plaza, holds the inn and smithy, and is where most of the Zora spend their daylight hours. A staircase beyond the statue memorializing Mipha leads slightly downward into a cave-like chamber where, standing in a pool of water, resides a Sheikah shrine. The fact that this exists here, just below the Throne Room, is a testament to the trust that exists between the far-flung peoples of Hyrule. Directly above this shrine chamber, sandwiched between it and the Throne Room, are the night pools: three ponds in which the Zora sleep. Two guards stand watch here during the darkness, and glowing snails make their homes among the pools. The pools are communal, which explains why there are no individual homes to be found within the city — only an inn for travelers less accustomed to resting in water. The second level is reached via two grand staircases which spring up from the central plaza, and further stairs into the Throne Room follow on their heels.

This chamber, open to the elements through an arcade, is both a testament to Zora architecture and community. Raised benches hug the sides of the room, offering seating for likely the entire population of the Zora, and a petitioner’s platform rises slightly in front of the throne, emblazoned with their sacred symbol. A huge opalescent dome looks down upon the king, patterned after the shape of a whale’s tail. Water falls from all sides of the room, cascading downward to the pool of rivers underneath the Domain. Unlike in Gerudo Town, where control over the water was largely to signify power and divinity, here it is a symbol of generosity and plenty. The king sits ensconced at the fountainhead of Hyrule, the very manifestation of bounteousness and nobility — he who freely gives life to the land. And surrounding him is a city as fluid, stunning, and as vital as the element to which it is bound: a necklace over the heart of the world.

Notes and Works Cited:

[1] “By 1920, as we have seen, Jastrow realized that the Sumerian Deluge, like the earlier-discovered fragments of the Akkadian Atrahasis Epic, confirmed that the flood story was originally independent of Gilgamesh.” (p. 23)

“While the third Sumerian composition, The Deluge, corresponds to the report of the flood heard by Gilgamesh in Tablet XI, Kramer noted that the story had, just as Jastrow believed, no original connection with traditions or literature about Gilgamesh. It was, instead, part of a separate narrative beginning with creation and continuing through the flood to the immortalization of the hero. It has since become clear that this Sumerian composition is actually a counterpart of the Akkadian Atrahasis Epic, and that the flood narrative came to Gilgamesh through The Atrahasis Epic, rather than directly from The Deluge.” (p. 25)

“The Sumerian Sources of the Akkadian Epic.” The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic, by Jeffrey H. Tigay, Bolchazy-Carducci, 2002, pp. 23–25.

[2] “For some reason, however, the gods determined to destroy mankind with a flood. Enki (Akkadian: Ea), who did not agree with the decree, revealed it to Ziusudra (Utnapishtim), a man well known for his humility and obedience. Ziusudra did as Enki commanded him and built a huge boat, in which he successfully rode out the flood. Afterward, he prostrated himself before the gods An (Anu) and Enlil, and, as a reward for living a godly life, Ziusudra was given immortality.”

Some level of similarity should be obvious: both survivors are righteous men who receive warnings (from deities) to build large vessels in order to outlast a flood that will soon sweep the land at the behest of the divine. And yet there are distinct differences: while the gods of the Eridu Genesis have no known motive for destroying the world, the biblical God desired to rid the world of the wickedness of humanity; Ziusudra was granted immortality, while Noah was part of a covenant between God and humanity which ensured that God would no longer flood the world. There are other, more cosmetic differences, as well, but these strike me as the largest narrative differences.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Eridu Genesis.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 7 Nov. 2019, www.britannica.com/topic/Eridu-Genesis#ref234407.

[3] “It is generally accepted that marine fossils found far inland influenced the myth of Deucalion’s Flood. As the historian Solinus wrote, the receding waters of the flood ‘left behind shells and fishes and many other things, making the inland hills resemble the seashore.’”

“Chapter V: Mythology, Natural Philosophy, and Fossils.” The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times, by Adrienne Mayor, Princeton University Press, 2001, p. 210.

[4] Dundes, Alan. The Flood Myth. University of California Press, 1988.

Author’s Note: Róheim’s essay begins on page 151, and Dundes’s on page 167. Dundes ends his piece with this rather scathing remark, which I simply must include:

“Finally, if flood myths are truly male myths of creation, we can better understand why male scholars, including theologians, have been so concerned with studying them. Just as a male-dominated society created the myths in the first place, so modern males, increasingly threatened by what they perceive as angry females dissatisfied with ancient myths which give priority to males, cling desperately to these traditional expressions of mythopoeic magic. . . . The vehemence and vigor with which defenders of the faith insist that the flood myth represents historical (and not psychological) reality may well involve much more than a test of Judeo-Christian dogma and belief. It may represent instead or in addition a last bastion of male self-delusion.”

[5] Bodde, Derk. “Myths of Ancient China.” In Mythologies of the Ancient World, ed. Samuel Noah Kramer, Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1961, p. 398.

[6] “Deities, Themes, and Concepts.” Handbook of Chinese Mythology, by Lihui Yang et al., Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 114–117.

[7] Ibid.

“. . . the spirit is praised for making every effort to conquer the natural disaster, no matter how arduous the task is, in order to save humans.”

[8] Wu, Kuo-cheng. The Chinese Heritage. Crown, 1982, p. 69.

[9] Ibid., 85.

[10] Theobald, Ulrich. “Gun 鯀.” China Knowledge, 23 Jan. 2012,

http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Myth/personsgun.html

“For his theft, the Celestial Emperor ordered the fire god Zhu Rong to kill Gun at Yuxiao. Yet his corpse did not decay, and when it was opened with a knife, a dragon sprang out of his belly and ascended to the sky. The dragon was nobody else than Yu the Great.”

Or, “He thereupon rebelled and transformed into a fierce animal but was killed by Emperor Shun.”

[11] Wu, Kuo-cheng. The Chinese Heritage. Crown, 1982, p. 89.

[12] Theobald, Ulrich. “Yu the Great 大禹.” China Knowledge, 23 Jan. 2010, www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Myth/personsyu.html.

“Commentators interpret the former [the dragon] as a kind of dredge , the latter [the turtle] as a dam.”

[13] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 273.

[14] Ibid., 399.

[15] History of the Zora, The Eternal Zora's Domain, as told by King Dorephan

The rains have blessed Lanayru since ancient times with an abundance of pure, clean water. Seeking a bounty of such water, the Zora gathered there. Thus, as the legends go, the domain was born 10,000 years ago. The land was also rich in ore, and so a unique form of stonemasonry was developed to create our new home. The domain is one giant sculpture, a feat of architecture that has drawn admirers from the world over. Our great domain will ever stand as a hallmark of the esteemed artists who made it, an eternal symbol of Zora pride.

[16] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 111.

[17] Here are the stories gathered from around Zora’s Domain: https://www.zeldadungeon.net/wiki/Zora_Stone_Monuments

[18] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 273.

[19] Ibid., 281.

[20] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 274.

[21] I didn’t want to clutter the actual text with this impression, but it does remind me of Rivendell in Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring film, which was based on the sketches of Alan Lee — from the hidden vale in which it rests to its airiness, as well as the vaguest of impressions that, due to the age and memory of its inhabitants, one has somehow stepped out of mortal time into something else.

[22] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 112.

[23] “In Search of New Standards : the Late Nineteenth Century.” The Story of Art. Luxury Edition. Reprint, by E. H. Gombrich, Phaidon Press Ltd., 2016, p. 529.

Author’s Note: I can’t recommend highly enough both this book and his A Little History of the World. The latter, written for children (mostly), is an absolute charmer.

[24] McKean, Charles. “The Twentieth Century.” Architecture of the Western World, edited by Michael Raeburn, Orbis, 1980, p. 248.

Note: This recommendation on interior design is a paraphrase of C.F.A. Voysey, an important advocate of the Arts and Crafts movement.

[25] “Chapter 24: Europe and America, 1900 to 1945.” Gardner's Art through the Ages. the Western Perspective, by Fred S. Kleiner and Helen Gardner, 13th ed., vol. 2, Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010, pp. 678–679.

[26] McKean, Charles. “The Twentieth Century.” Architecture of the Western World, edited by Michael Raeburn, Orbis, 1980, p. 249.

Note: The emphasis is my own.

[27] Miller, Judith. DK Collector's Guides: Art Nouveau. DK, 2004, p. 69.

[28] Ibid., 142.

[29] Some artists and design firms stand above the rest, though, in terms of their ties to the Zora. While there are not a ton of images in the public domain (in fact I found it rather hard to find any, and the galleries I reached out to demurred, so you may want to search these on your own), the works of René Lalique, Levinger & Bissinger, Carl Hermann Pforzheim, Georges Fouquet, Murrle Bennett, and Theodor Fahrner provide the clearest connection.

[30] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 280.

[1] “By 1920, as we have seen, Jastrow realized that the Sumerian Deluge, like the earlier-discovered fragments of the Akkadian Atrahasis Epic, confirmed that the flood story was originally independent of Gilgamesh.” (p. 23)

“While the third Sumerian composition, The Deluge, corresponds to the report of the flood heard by Gilgamesh in Tablet XI, Kramer noted that the story had, just as Jastrow believed, no original connection with traditions or literature about Gilgamesh. It was, instead, part of a separate narrative beginning with creation and continuing through the flood to the immortalization of the hero. It has since become clear that this Sumerian composition is actually a counterpart of the Akkadian Atrahasis Epic, and that the flood narrative came to Gilgamesh through The Atrahasis Epic, rather than directly from The Deluge.” (p. 25)

“The Sumerian Sources of the Akkadian Epic.” The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic, by Jeffrey H. Tigay, Bolchazy-Carducci, 2002, pp. 23–25.

[2] “For some reason, however, the gods determined to destroy mankind with a flood. Enki (Akkadian: Ea), who did not agree with the decree, revealed it to Ziusudra (Utnapishtim), a man well known for his humility and obedience. Ziusudra did as Enki commanded him and built a huge boat, in which he successfully rode out the flood. Afterward, he prostrated himself before the gods An (Anu) and Enlil, and, as a reward for living a godly life, Ziusudra was given immortality.”

Some level of similarity should be obvious: both survivors are righteous men who receive warnings (from deities) to build large vessels in order to outlast a flood that will soon sweep the land at the behest of the divine. And yet there are distinct differences: while the gods of the Eridu Genesis have no known motive for destroying the world, the biblical God desired to rid the world of the wickedness of humanity; Ziusudra was granted immortality, while Noah was part of a covenant between God and humanity which ensured that God would no longer flood the world. There are other, more cosmetic differences, as well, but these strike me as the largest narrative differences.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Eridu Genesis.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 7 Nov. 2019, www.britannica.com/topic/Eridu-Genesis#ref234407.

[3] “It is generally accepted that marine fossils found far inland influenced the myth of Deucalion’s Flood. As the historian Solinus wrote, the receding waters of the flood ‘left behind shells and fishes and many other things, making the inland hills resemble the seashore.’”

“Chapter V: Mythology, Natural Philosophy, and Fossils.” The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times, by Adrienne Mayor, Princeton University Press, 2001, p. 210.

[4] Dundes, Alan. The Flood Myth. University of California Press, 1988.

Author’s Note: Róheim’s essay begins on page 151, and Dundes’s on page 167. Dundes ends his piece with this rather scathing remark, which I simply must include:

“Finally, if flood myths are truly male myths of creation, we can better understand why male scholars, including theologians, have been so concerned with studying them. Just as a male-dominated society created the myths in the first place, so modern males, increasingly threatened by what they perceive as angry females dissatisfied with ancient myths which give priority to males, cling desperately to these traditional expressions of mythopoeic magic. . . . The vehemence and vigor with which defenders of the faith insist that the flood myth represents historical (and not psychological) reality may well involve much more than a test of Judeo-Christian dogma and belief. It may represent instead or in addition a last bastion of male self-delusion.”

[5] Bodde, Derk. “Myths of Ancient China.” In Mythologies of the Ancient World, ed. Samuel Noah Kramer, Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1961, p. 398.

[6] “Deities, Themes, and Concepts.” Handbook of Chinese Mythology, by Lihui Yang et al., Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 114–117.

[7] Ibid.

“. . . the spirit is praised for making every effort to conquer the natural disaster, no matter how arduous the task is, in order to save humans.”

[8] Wu, Kuo-cheng. The Chinese Heritage. Crown, 1982, p. 69.

[9] Ibid., 85.

[10] Theobald, Ulrich. “Gun 鯀.” China Knowledge, 23 Jan. 2012,

http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Myth/personsgun.html

“For his theft, the Celestial Emperor ordered the fire god Zhu Rong to kill Gun at Yuxiao. Yet his corpse did not decay, and when it was opened with a knife, a dragon sprang out of his belly and ascended to the sky. The dragon was nobody else than Yu the Great.”

Or, “He thereupon rebelled and transformed into a fierce animal but was killed by Emperor Shun.”

[11] Wu, Kuo-cheng. The Chinese Heritage. Crown, 1982, p. 89.

[12] Theobald, Ulrich. “Yu the Great 大禹.” China Knowledge, 23 Jan. 2010, www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Myth/personsyu.html.

“Commentators interpret the former [the dragon] as a kind of dredge , the latter [the turtle] as a dam.”

[13] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 273.

[14] Ibid., 399.

[15] History of the Zora, The Eternal Zora's Domain, as told by King Dorephan

The rains have blessed Lanayru since ancient times with an abundance of pure, clean water. Seeking a bounty of such water, the Zora gathered there. Thus, as the legends go, the domain was born 10,000 years ago. The land was also rich in ore, and so a unique form of stonemasonry was developed to create our new home. The domain is one giant sculpture, a feat of architecture that has drawn admirers from the world over. Our great domain will ever stand as a hallmark of the esteemed artists who made it, an eternal symbol of Zora pride.

[16] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 111.

[17] Here are the stories gathered from around Zora’s Domain: https://www.zeldadungeon.net/wiki/Zora_Stone_Monuments

[18] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 273.

[19] Ibid., 281.

[20] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 274.

[21] I didn’t want to clutter the actual text with this impression, but it does remind me of Rivendell in Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring film, which was based on the sketches of Alan Lee — from the hidden vale in which it rests to its airiness, as well as the vaguest of impressions that, due to the age and memory of its inhabitants, one has somehow stepped out of mortal time into something else.

[22] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 112.

[23] “In Search of New Standards : the Late Nineteenth Century.” The Story of Art. Luxury Edition. Reprint, by E. H. Gombrich, Phaidon Press Ltd., 2016, p. 529.

Author’s Note: I can’t recommend highly enough both this book and his A Little History of the World. The latter, written for children (mostly), is an absolute charmer.

[24] McKean, Charles. “The Twentieth Century.” Architecture of the Western World, edited by Michael Raeburn, Orbis, 1980, p. 248.

Note: This recommendation on interior design is a paraphrase of C.F.A. Voysey, an important advocate of the Arts and Crafts movement.

[25] “Chapter 24: Europe and America, 1900 to 1945.” Gardner's Art through the Ages. the Western Perspective, by Fred S. Kleiner and Helen Gardner, 13th ed., vol. 2, Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010, pp. 678–679.

[26] McKean, Charles. “The Twentieth Century.” Architecture of the Western World, edited by Michael Raeburn, Orbis, 1980, p. 249.

Note: The emphasis is my own.

[27] Miller, Judith. DK Collector's Guides: Art Nouveau. DK, 2004, p. 69.

[28] Ibid., 142.

[29] Some artists and design firms stand above the rest, though, in terms of their ties to the Zora. While there are not a ton of images in the public domain (in fact I found it rather hard to find any, and the galleries I reached out to demurred, so you may want to search these on your own), the works of René Lalique, Levinger & Bissinger, Carl Hermann Pforzheim, Georges Fouquet, Murrle Bennett, and Theodor Fahrner provide the clearest connection.

[30] White, Keaton C. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion. Dark Horse Books, 2018, p. 280.