Lurelin Village

“Gradually the magic of the island settled over us as gently and clinglingly as pollen. Each day had a tranquility, a timelessness, about it so that you wished it would never end. But then the dark skin of night would peel off and there would be a fresh day waiting for us, glossy and colorful as a child’s transfer and with the same tinge of unreality.”

— Gerald Durrell, My Family and Other Animals

Notwithstanding the fact that Lurelin Village was settled not upon an island but upon the coast of a much larger continent, the quote above enchantingly evinces the image that Lurelin has left lingering in my mind: one of the slow-roving sun passing imperceptibly overhead, until one realizes that sunrise has changed from unreachable zenith to sunset, each proclaiming itself upon the receptive blue palette of the sea. As with all coastal settlements, the sea diminishes everything; nothing manmade can hope to overcome the enthralling rhythms and moods of the ocean. Mankind can, with its cities, master a hill, valley, or even a mountain, but never the sea: it is beyond us. Attempting such a feat would, I imagine, be baffling to any reasonable society that has built itself upon the shore, for such people inevitably know that the ocean has outlasted (and will outlast) them in every conceivable trajectory of time. There are countless lessons we can learn from life near the water, and some few of them become reified through architecture. Lurelin Village has much to teach us.

— Gerald Durrell, My Family and Other Animals

Notwithstanding the fact that Lurelin Village was settled not upon an island but upon the coast of a much larger continent, the quote above enchantingly evinces the image that Lurelin has left lingering in my mind: one of the slow-roving sun passing imperceptibly overhead, until one realizes that sunrise has changed from unreachable zenith to sunset, each proclaiming itself upon the receptive blue palette of the sea. As with all coastal settlements, the sea diminishes everything; nothing manmade can hope to overcome the enthralling rhythms and moods of the ocean. Mankind can, with its cities, master a hill, valley, or even a mountain, but never the sea: it is beyond us. Attempting such a feat would, I imagine, be baffling to any reasonable society that has built itself upon the shore, for such people inevitably know that the ocean has outlasted (and will outlast) them in every conceivable trajectory of time. There are countless lessons we can learn from life near the water, and some few of them become reified through architecture. Lurelin Village has much to teach us.

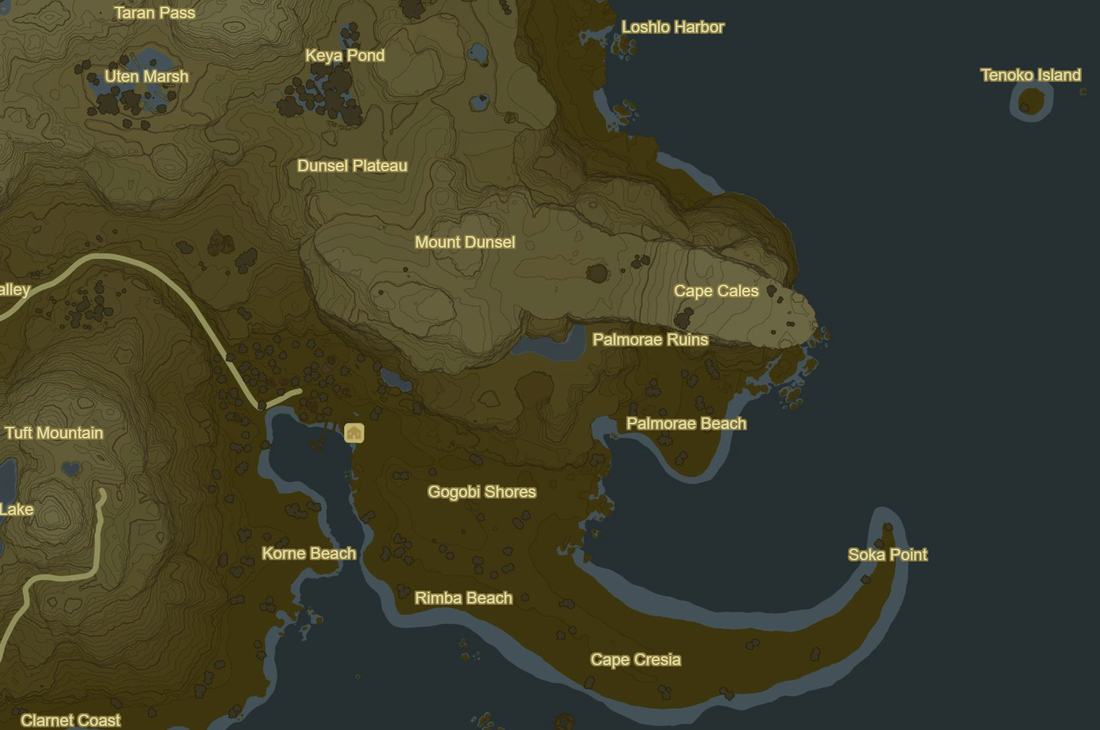

Geographically, Lurelin is in the utmost southeastern corner of Hyrule, beneath Tuft Mountain and Mount Dunsel; a branch of road far from the main trunk of Hyrulean wayfaring cuts its way through Atun Valley, eventually terminating in a small twig of a path near an inlet on the Gogobi Shores of the Necluda Sea. A southern position, warm currents, and tropical winds all combine to form a nearly-perfect climate, with comfortable temperatures and frequent rains. Given the beauty of this location, it seems strange that travel here is never mandatory during the unfolding of the game’s narrative — to visit Lurelin, then, is to visit simply for pleasure. And perhaps that is part of its allure.

|

A cape is a promontory or high point of land that extends narrowly into a larger body of water, usually the sea. Upon seeing Cape Cresia for the first time, I was immediately reminded of Cape Cod in Massachusetts. Its distinct shape, formed largely by retreating glaciers, makes it one of the most instantly-recognizable capes in the world.

|

As a fishing village, and one primarily concerned with life on and near the sea, most of the culture in this area takes its form and function from the ocean. While there are only six structures in the village — four houses, the inn, and a game shop — there are three docks and many different rafts, boats, and canoes scattered along the beach. The sea and land meet gently along these shores, and slow, patient fish dot the waters of the estuary around the community; myriad palms stand among the buildings, curving or straight, and nearly all of them laden with fruit. Many of the villagers cook outside in large cooking pots, which hints at a deeply communal society. The inhabitants themselves seem perfectly insouciant; they stand gazing out to sea, cook when the time comes, take reflective walks along reflective waters, and never seem to exhibit a sense of urgency. The major travail of Hyrule — the irruption of Calamity Ganon — extended not to this region, and the biggest threats to peace seem the frequent and sudden rain-showers, which cause only the slightest, uncommitted increase in pace in those caught outside.

Both Lurelin and Hateno managed to avoid the terrible destruction of a century ago, and as the only two Hylian settlements in the land, they maintain some small element of commerce and conviviality between them. Strangely, there is no direct road from Hateno to Lurelin; although the two are very close geographically, unbroken mountains and wetlands separate the two, making the only road from one to the other an extremely circuitous one. One imagines this route is seldom taken. Yet, another option presents itself, though there is little extant proof for its existence. Northeast from Lurelin and southeast from Hateno, directly along the coast, exists Loshlo Harbor, and although there are currently no boats, ships, or docks on its beaches, its nomenclature (and the presence of a road leading to it from Hateno Village) seems to suggest a past anchorage. Although this is but speculation, it stands to reason that these two settlements were once linked by water, given both the great distance that would have to be traversed over land and the heavy ties of Lurelin Village to ship-making and the coast. There are two primary connections with Hateno Village known to us: on a gentle knoll in the village, Hateno Cows are raised in a small enclosure; and there seems to be some intermarriage between the peoples of these settlements. Relera, the village elder’s daughter, moved to Hateno Village after marrying her husband, Rhodes, who is a miller there. She can often be found near the windmills above Hateno, reminiscing about her hometown of Lurelin by the sea.

Given the longing that Relera feels for her village, we should now seek to understand just what beauty and grace give Lurelin its charm. I mentioned before that most cultural objects to be found here take their form and function from the sea, but that is not their only source of inspiration — we must also look to the trees.

Both Lurelin and Hateno managed to avoid the terrible destruction of a century ago, and as the only two Hylian settlements in the land, they maintain some small element of commerce and conviviality between them. Strangely, there is no direct road from Hateno to Lurelin; although the two are very close geographically, unbroken mountains and wetlands separate the two, making the only road from one to the other an extremely circuitous one. One imagines this route is seldom taken. Yet, another option presents itself, though there is little extant proof for its existence. Northeast from Lurelin and southeast from Hateno, directly along the coast, exists Loshlo Harbor, and although there are currently no boats, ships, or docks on its beaches, its nomenclature (and the presence of a road leading to it from Hateno Village) seems to suggest a past anchorage. Although this is but speculation, it stands to reason that these two settlements were once linked by water, given both the great distance that would have to be traversed over land and the heavy ties of Lurelin Village to ship-making and the coast. There are two primary connections with Hateno Village known to us: on a gentle knoll in the village, Hateno Cows are raised in a small enclosure; and there seems to be some intermarriage between the peoples of these settlements. Relera, the village elder’s daughter, moved to Hateno Village after marrying her husband, Rhodes, who is a miller there. She can often be found near the windmills above Hateno, reminiscing about her hometown of Lurelin by the sea.

Given the longing that Relera feels for her village, we should now seek to understand just what beauty and grace give Lurelin its charm. I mentioned before that most cultural objects to be found here take their form and function from the sea, but that is not their only source of inspiration — we must also look to the trees.

The homes and businesses of Lurelin Village can all be found built upon stands of rock throughout the community, likely as a precaution against flooding and rising tides. They are further raised on wooden piers, giving them the appearance of resting against small docks.

The homes are built in one grand tradition, while the mercantile buildings seem to be modeled directly after trade-ships. Where then do the houses take their inspiration? They are, for the life of me, modeled on the coconut. Each home is built around a central palm tree, shaded by its leaves and supported by its trunk; it is as if the house grew round and ripe within the canopy, and, when the time came, fell to earth like a mature fruit. Even though they may have fallen from above, still each house is set upon a foundation of six posts: like six radiating spokes of a wheel. These wooden posts bend upward through the structure, creating six bays — the spaces between architectural elements (in this case the areas of wall between the six posts) — of equal size. These bays have set functions in Lurelin domestic architecture: bay one holds the open-air door, bays two and three hold open-air windows, bays four and five are of solid wood, and the sixth bay (being the bay opposite the door, considered the back of the house) contains a small slatted window. As has been said, several of these houses have a surrounding porch, making them look like docks in themselves, while others are simply held up by the six posts.

Each house has a rounded husk of dark wood, painted on the bottom half with a wave-stirred sea of white. Notice also the central palms of the homes, erupting from the tufts of thatch upon each house.

The interior ceilings branch into eight winding beams, and support the iconic thatched roofs of the settlement. The roofs are all of a kind: four unequal tiers — beginning at the base with the largest two, slightly angled, separated by a light paint, interrupted by a double-coiled length of rope, and terminating at the top with two spiked tufts. From these roofs hang the symbol of the village, a white swirl on brilliant orange. For these are the colors of the village, being found upon the flags, ceramics, baluster decorations (which are little white-and-orange fish), rugs, and other cultural artifacts. This symbol itself seems to be taken from the Māori, where this spiral shape is called a koru, or “loop”. This symbol, “often used in Māori art as a symbol of creation, is based on the shape of an unfurling fern frond. Its circular shape conveys the idea of perpetual movement, and its inward coil suggests a return to the point of origin. The koru therefore symbolizes the way in which life both changes and stays the same.” [1] How fitting, for a people who know the changes and permanence of the sea! Here is one of the lessons of Lurelin: as the sea’s face changes, so it remains the sea; as humanity’s face changes, so it remains humanity. While life changes, Life remains the same.

|

The eight branching beams of the ceiling, anchored to the palm.

|

Notice the koru pennants hanging from the roofline of the houses.

|

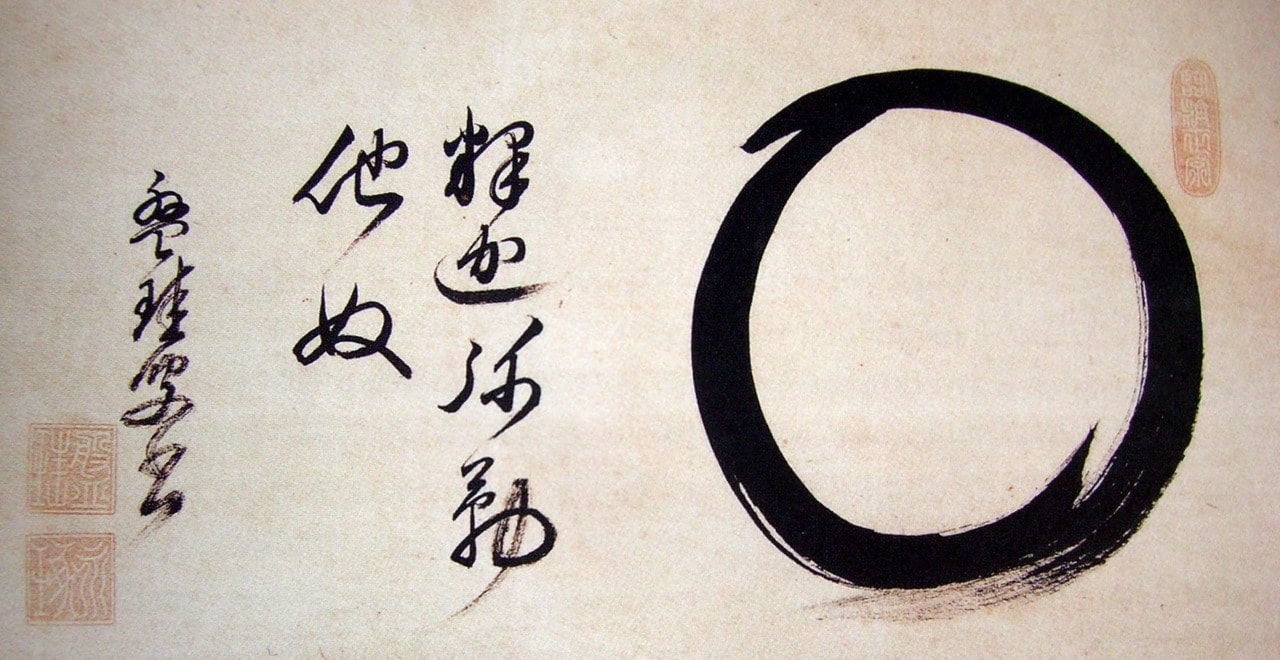

Looking to the interiors of the houses, we find a charming scene. The windows do have wooden blinds, though they are not evidently created to keep out insects; given that there are no doors and only open-air windows, we must conclude that there are either no bugs to be found in this region, or that they do not interfere with human life to an intolerable degree. These blinds, then, must be for lighting and ventilation, a very reasonable invention for a people living in a tropical region near the sea. Curiously, these shades bear the ensō, a long-esteemed symbol of Buddhism raised to stylistic perfection by Zen masters. The ensō are “symbols of teaching, reality, enlightenment, and a myriad of things in between . . . . Ensō evoke power, dynamism, charm, humor, drama, and stillness.” [2] This is surely a large task for such a seemingly-simple form; after all, surely a circle is a circle? Well, yes and no — it is simple, and yet it is ineffably complex. As a motion, it is simple: it is a design of one or two brushstrokes that catch a singular moment in time. It is deceptively minimalistic, though books have been written on the topic of the ensō; each person brings a personality to the canvas, and, with such a simple form and execution, the personality truly shines through. It is one person, with one brush, with one motion, creating one circle — open, closed, symmetrical, lopsided, black, green, white, blue, fast, slow, large, small, quaint, profound. For many, it is continual practice: letting one’s nature express itself in a pure form, if only momentarily. What, then, is this design doing in Lurelin Village? All things considered, I am unsure. It could represent the spontaneity and pure nature of the villagers, it could be an aspirational reminder of simplicity and enlightenment, it could be the pale moon captured in a single brushstroke, or it could simply be an incomplete circle currently in fashion. The symbol-loving of us will of course tend toward the former descriptions, even though we must ultimately remain agnostic. Yet, where symbols exist, they are read and given meaning, and the presence of the ensō adds a further depth of nuance and mystery to the humble trappings of this backwater culture.

|

The ensō of Lurelin Village.

|

An ensō by Bankei Yōtaku - Image in the Public Domain

|

What else can we discover through the interior? There are the expected ropes, harpoons, and potted plants, but now we find small banners surrounding the inner palm, papers with scrawled words, water skis, woven baskets, fabrics bearing the koru motif, and beautiful textiles exhibiting the craftsmanship present in the village. The beds are cloth stretched tight over low-lying wooden frames; they showcase orange waves and a triangular design imitating a mountain island jutting out from the ocean. The thatched, woven rugs are of particular note; they are perfectly circular, wrapping around the trunk of the inner palm, dyed with soft oranges and blues. They bear aerial abstracts of fish and shells, beautifully embellished, with a fine attention to detail. This fish symbol upon the rug is the same as that on the Fisherman’s Shield, tentatively linking their production to this village. At night the interiors of these houses are particularly calming, with soft moonlight breaking upon the floor through the wooden shades and warm lamplight reflecting brilliantly off the lacquered wooden floors. There are beds for leisure, small desks for writing and reading, porches for stargazing, and much attention paid to the display of curios and culture — subtle hints of leisure and personality.

Outside of these charming houses can be found many functional artifacts: plants in orange pots decorated with a curvilinear design in white paint, nets and lines for drying clothes and seafood, and shelves with cooking implements, among which are cups, bowls, mortar and pestle, and various storage jars likely filled with grains. A common dish in Lurelin is paella, a meal from Mediterranean Spain consisting of rice, seafood, vegetables, and spices, which “symbolizes the union and heritage of two important cultures, the Roman which gave us the utensil [the name for the traditional pot used in making paella is from the Latin patella — little pan] and the Arab which brought us the basic food of humanity for centuries: rice.” [3] In Lurelin, seafood paella can be created by preparing any porgy or the Hearty Blueshell Snail with Hylian Rice, goat butter, and rock salt. These meals are cooked out of doors in a communal setting, centered around the ever-present hearth of Hyrule: the cooking pot.

As with all the settlements we have discussed thus far, Lurelin too marks its boundaries with decorative gates, though in this case they are more posts which give the impression of gates. There are three in total, marking each path in and out of the settlement, and they are all made of rough timber, though noticeably not of palm-wood. The rough timber, braced with smaller logs, curves as though to form an arch; it is not known whether it was harvested like this, or if the curve was induced. Put together, the four bending logs would form an arch, but separated as they are, they give me the same anticipation and sense of expectancy to be found in the broken pediments of the Baroque Period. Again, through the use of negative space, they impress upon one the sense of a gate without actually forming a physical gate. To me, this is fascinating. Adorning the “half-arch” of each post are red and yellow ribbons, furled tightly around the topmost beams; beneath these ribbons are smaller posts hung with lanterns, forming the last piece to this wonderful architectural setting.

As with all the settlements we have discussed thus far, Lurelin too marks its boundaries with decorative gates, though in this case they are more posts which give the impression of gates. There are three in total, marking each path in and out of the settlement, and they are all made of rough timber, though noticeably not of palm-wood. The rough timber, braced with smaller logs, curves as though to form an arch; it is not known whether it was harvested like this, or if the curve was induced. Put together, the four bending logs would form an arch, but separated as they are, they give me the same anticipation and sense of expectancy to be found in the broken pediments of the Baroque Period. Again, through the use of negative space, they impress upon one the sense of a gate without actually forming a physical gate. To me, this is fascinating. Adorning the “half-arch” of each post are red and yellow ribbons, furled tightly around the topmost beams; beneath these ribbons are smaller posts hung with lanterns, forming the last piece to this wonderful architectural setting.

|

Above: As dusk settles in, the hanging sconces are lit, the fire mirroring the colors of the bright ribbons set in the beams above.

Right: A close-up of one of the architectural pieces of this "gate". The first post carries the lantern, the following two hold the colored ribbons, and the final two beams support the entire structure from behind, increasing the gate's integrity. |

Akin to these gate-posts are the awnings and umbrellas found around the village that offer some small protection from the elements. The largest awnings, opaque and orange, can be found over the dockside shop, while the smaller umbrellas can often be found protecting little benches and vantage points — illuminating some of the values of the people of Lurelin. Given the slight bend in the wood and the arrangement of the supporting rods, the umbrellas seem to blend together in the form of a palm tree with the webbing of a fish’s fin. Of course, another reading could be of the unfurled sail filled with wind. Either way, the theme is appropriately maritime. Given the adoring attitude the villagers have toward scenery, these small spots are hung with lanterns for night-time viewing of the sea, mountains, and moon.

The two remaining structures in Lurelin Village — an inn called the Fishing Resort and a game salon called the Treasure Chest Shop — take the shape of larger, more traditional ships. In many ways, these two buildings reflect the same design elements of the houses: they are supported and divided into bays by six posts, painted in the same color scheme, decorated with the same motifs, and made of the same materials. Of course, we should be expectant of similarities; so, we must look to the differences. While the game salon is built around one palm (suspended in a pot in the ceiling!), the inn’s main support is actually three palms twisted and grown around one another into a larger tree; also serving as a bookshelf, it forms the main design element in the inn. The inn’s exterior is bedecked in banners, flags, and strips of cloth, and inside is much simpler: there is a ceiling of simple rafters and wood, with four separate beds for customers. In contrast to this, the roof of the game salon rests above a clerestory of open-air windows. Each of its lower windows is graced by a planter of pink flowers, and the ship is further embellished by large rupees, ensō symbols painted upon the blinds, and a large fan motif carrying another curious symbol — the third to be found in Lurelin, though one unknown to me. It is indeed odd that there are no large ships to be found in the village, given that the two principal structures of the town are themselves large ships. Yet, all of these oceanside design elements serve their function beautifully: they create an overall impression that is larger and more intense than the sum of its parts. For while we may forget the number of bays in Lurelin’s houses, or which fish is placed upon which post, the lasting memory of Lurelin — that of a people embedded on the coast, reflecting their location through culture — will remain.

|

Following deeply in an oceangoing tradition are the boats of the village, which are crafted in the likeness of whales. Not only is the form cetacean, with its fluted tail and rotund body, but so too is the ship’s hull coated with barnacles and engraved with a large eye. These boats are intensely charming, and suggest that somewhere in the ocean surrounding Hyrule reside real leviathans, for where else would this design originate?

|

Here can be seen the Treasure Chest Shop, a game salon predicated upon gambling and guesswork. The prow of this ship curves drastically upward, and carries the same pennants found upon the houses. So too are the shades and their ensō symbols the same. Toward the back of the ship, under the circular roof, can be found the clerestory windows which illuminate the interior of the shop. The fan-shaped symbol in the middle is unknown.

|

Given its positioning in the hinterlands of Hyrule and its bucolic unimportance to the plot of Breath of the Wild, it is odd that so many people are so taken with Lurelin Village. But, actually, this is not so strange; many times, we are drawn to places that embody serenity and cultivate quietude. For the world as full of troubles as it is, and always seems to be, it is a balm for the mind to remember that such places exist unblemished and at peace. For even though larger Hyrule has been left to misery and misfortune, still we would not wish hardship on all peoples simply to make suffering more widespread and equal; the protection of the whole and the good, even when so much has befallen others, should not embitter but embolden our actions in the world. Eventually, we would see all places become as peaceful, creative, and wholesome as this one, for these are the small places that make the larger world worth saving.

And so we leave Lurelin Village to endure its small changes, so many scattered husks on the beaches of a sapphire sea.

And so we leave Lurelin Village to endure its small changes, so many scattered husks on the beaches of a sapphire sea.

Notes and Works Cited:

[1] Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal, 'Māori creation traditions - Common threads in creation stories', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 8 Feb. 2005, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/photograph/2422/the-koru.

[2] Seo, Audrey Yoshiko. “Introduction.” Enso: Zen Circles of Enlightenment, Weatherhill, 2009.

[3] Davidson, Alan, and Soun Vannithone. The Oxford Companion to Food. Edited by Tom Jaine, 3rd ed., Oxford University Press, 2014

[1] Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal, 'Māori creation traditions - Common threads in creation stories', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 8 Feb. 2005, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/photograph/2422/the-koru.

[2] Seo, Audrey Yoshiko. “Introduction.” Enso: Zen Circles of Enlightenment, Weatherhill, 2009.

[3] Davidson, Alan, and Soun Vannithone. The Oxford Companion to Food. Edited by Tom Jaine, 3rd ed., Oxford University Press, 2014