Tarrey Town and Modular Hyrulean Architecture

"[Prefabrication] challenges architecture's most deep-seated prejudices. It calls into question the concept of authorship, which is central to architecture's view of itself as an art form; it insists on a knowledge of production methods, marketing and distribution as well as construction; it disallows architecture's normal obsession with the needs of the individual clients and the specific qualities of particular places; and its lightweight, portable technologies mock architecture's monumental pretension. But if architecture could adapt itself to these conditions and succeed in [prefabrication], then it might recover some of the influence it has lost in the last 30 years and begin to make a real difference to the quality of the built environment."

— Colin Davies, The Prefabricated Home

"What can be labeled, packaged, mass produced is neither truth nor art."

— Marty Rubin

Author’s Note: I have unwittingly opened a Pandora’s Box of architecture. In approaching Tarrey Town, I imagined a short piece enumerating its architectural elements, perhaps touching upon cosmopolitanism and trade, ultimately ending on a note both optimistic and urbane. I may yet do that, but the route has grown more circuitous. It is of course my fault for not expecting a minefield in this area in which traditional aesthetic philosophy and modern necessity collide, but let this serve as a reminder that no subject area is insulated against internecine conflict. Here are fundamental issues of artistry and creativity strung between the two poles of industry and inspiration. These struggles pit authorship against collective need and production against purity. Let’s begin in the trenches.

— Colin Davies, The Prefabricated Home

"What can be labeled, packaged, mass produced is neither truth nor art."

— Marty Rubin

Author’s Note: I have unwittingly opened a Pandora’s Box of architecture. In approaching Tarrey Town, I imagined a short piece enumerating its architectural elements, perhaps touching upon cosmopolitanism and trade, ultimately ending on a note both optimistic and urbane. I may yet do that, but the route has grown more circuitous. It is of course my fault for not expecting a minefield in this area in which traditional aesthetic philosophy and modern necessity collide, but let this serve as a reminder that no subject area is insulated against internecine conflict. Here are fundamental issues of artistry and creativity strung between the two poles of industry and inspiration. These struggles pit authorship against collective need and production against purity. Let’s begin in the trenches.

As with all fields, architecture comes laden with assumptions, biases, and expectations. And as it is with all laymen looking upon such soft-spoken fields, architecture seems to be a relatively quiet and sensible area of study. While that general picture is largely true, there are still many views that have escaped consensus; various schools have their disparate thoughts about architecture’s definition, scope, and purpose, and individual architects can be scathing to a degree usually seen only in politics or academia.

Prefabrication and modular architecture are rather modern phenomena, and, like all idealistic novelties, they have disrupted the conversation and flow of their field. There is a foundational dissonance between the implicit tendencies and values of traditional and modern architecture, and this schism demands our attention. Colin Davies writes fascinatingly about the disconnect between Architecture proper and those things upon which it depends: industry, labor, and production. He writes that, "the relationship between architecture and prefabrication has always been problematic. Architects have found it hard to come to terms with the idea that the products of their art might be made in a factory. This is not surprising, perhaps. When the industrial revolution first stirred, architecture was already an ancient craft. Some have seen architecture as a bulwark of resistance against industrial culture, maintaining eternal values in a world driven mad by what money can buy." [1] In short, many architects believe themselves to be engaged in the crystallization of culture, all while ignoring the complex systems of trade, commerce, and industry that necessarily undergird their works. I too am guilty of such sentimental thoughts: I fail to see the carpenter behind the cathedral and the mason behind the marble. Yet architecture is a necessity required of all people, unlike painting or sculpture. And our shelters do not simply satisfy physical human needs; each home simultaneously represents a cultural moment in time. Because vernacular architecture is place- and material-bound, completely dependent upon local resources and creativity, prefabrication seems its opposite, as it takes neither into account. So already we have assaulted both tradition and a fidelity to native land and culture.

Prefabrication also assails the very concept of Authorship. Most artists (architects included) see themselves as the sole authors of their work, with each singular ornament fulfilling an inspired ideal. The whole is only possible stemming from one brain in a moment of insight or through the eureka of happenstance. One cannot separate a work from its author, and so to divide up the structure and its design between individuals, or, worse, to relegate creation to industry, seems almost sacrilegious. To place architecture at the heart of a factory — one more construction on an assembly line — insults our sensibilities: after all, we can’t imagine a world in which Caravaggio or Hokusai works are churned out to the tune of ten thousand an hour. How then can we place architecture where we cannot imagine sculpture or music? “Because these metaphors are imperfect,” those defenders of prefabrication might reply. “Architecture straddles the boundaries between necessity and luxury in a way that painting and sculpture do not; no one needs a daguerreotype to survive, but they damn well need a house. So don’t go on about the sacred process of architecture, indulging in Wildean fantasies of art for art’s sake. Of course we want to create things of beauty and permanence, but we simply want to do it in a manner that is realistic and useful.” And they may have a point.

Prefabrication and modular architecture are rather modern phenomena, and, like all idealistic novelties, they have disrupted the conversation and flow of their field. There is a foundational dissonance between the implicit tendencies and values of traditional and modern architecture, and this schism demands our attention. Colin Davies writes fascinatingly about the disconnect between Architecture proper and those things upon which it depends: industry, labor, and production. He writes that, "the relationship between architecture and prefabrication has always been problematic. Architects have found it hard to come to terms with the idea that the products of their art might be made in a factory. This is not surprising, perhaps. When the industrial revolution first stirred, architecture was already an ancient craft. Some have seen architecture as a bulwark of resistance against industrial culture, maintaining eternal values in a world driven mad by what money can buy." [1] In short, many architects believe themselves to be engaged in the crystallization of culture, all while ignoring the complex systems of trade, commerce, and industry that necessarily undergird their works. I too am guilty of such sentimental thoughts: I fail to see the carpenter behind the cathedral and the mason behind the marble. Yet architecture is a necessity required of all people, unlike painting or sculpture. And our shelters do not simply satisfy physical human needs; each home simultaneously represents a cultural moment in time. Because vernacular architecture is place- and material-bound, completely dependent upon local resources and creativity, prefabrication seems its opposite, as it takes neither into account. So already we have assaulted both tradition and a fidelity to native land and culture.

Prefabrication also assails the very concept of Authorship. Most artists (architects included) see themselves as the sole authors of their work, with each singular ornament fulfilling an inspired ideal. The whole is only possible stemming from one brain in a moment of insight or through the eureka of happenstance. One cannot separate a work from its author, and so to divide up the structure and its design between individuals, or, worse, to relegate creation to industry, seems almost sacrilegious. To place architecture at the heart of a factory — one more construction on an assembly line — insults our sensibilities: after all, we can’t imagine a world in which Caravaggio or Hokusai works are churned out to the tune of ten thousand an hour. How then can we place architecture where we cannot imagine sculpture or music? “Because these metaphors are imperfect,” those defenders of prefabrication might reply. “Architecture straddles the boundaries between necessity and luxury in a way that painting and sculpture do not; no one needs a daguerreotype to survive, but they damn well need a house. So don’t go on about the sacred process of architecture, indulging in Wildean fantasies of art for art’s sake. Of course we want to create things of beauty and permanence, but we simply want to do it in a manner that is realistic and useful.” And they may have a point.

Prefabrication is essentially pragmatic, as most architecture cannot exist in a Wrightian sense, wherein the structure balances both the natural setting and will of the clients. That is a lovely vision, to be sure, but in a world so increasingly populated and demanding, it seems untenable as a long-term solution to the exigencies of mass urbanization and climate change. It is in this gap between necessity and fancy that prefabrication announces itself as a potential alternative. Indeed, many architects of the twentieth century, including Le Corbusier, Wachsmann, Gropius (of the Bauhaus School of architecture), and Wright, as well as governmental organizations like the US Army, dabbled in the design, infrastructure, and production of the prefabricated house. Even before that, however, prefabrication was on the table in 1830’s Chicago, during the California Gold Rush, and even in the British Empire in the form of the Manning Portable Cottage. Davies intimates that these houses are not considered “architecture” by many academics because they lack the attachment to any famous architect or movement. [2] We seem to demand an architect in determining Architecture, just as we demand a composer when attending a symphony. Nevertheless, prefabrication was an enormous movement in twentieth-century America, at least in theory; companies like Sears Roebuck, General Houses Inc., and American Houses all put forward versions of the prefabricated home to the American public, to middling, but not long-term, success. Several governments, notably those of the United States and England, eventually became more involved around the war years, which yielded a growth in prefabricated production; in the United States, “the level of prefabrication had settled at about 10 per cent of total house production by the mid-1950s, although there were wide variations from one part of the country to another. In certain parts of the Midwest the proportion was more like 50 per cent.” [3] Yet prefab architecture never came to predominate the housing scene, often failing to meet expectations of quality, production, or competitiveness within the private market. Manufactured houses (those mass-produced to consumer specifications and prepared in factories), trailers, and mobile homes are significantly more popular, having had something of a heyday in the 1970s. Yet, through no lack of trying, it seems that prefabricated houses are lacking a vital something.

Now, this something could be many things, and it is likely multivariable in nature: some conglomeration of economics, manufacturing, housing norms, location, demand, and style. But, to me, the principal aspect can be discovered through a discussion of ideals. Were it possible for each person to have the house of their choice, no parameters whatsoever, just what exactly would those houses look like? Under those conditions, I would wager that more homeowners would choose to have personally-tailored homes built: spaces that spoke to place, to family needs, and to individual tastes. I may be wrong about this, but this is where my intuition leads me. I think I can defend this proposition a bit more, however, and will do so through a few different works.

“In postwar France, the theorist Gaston Bachelard wrote a study called The Poetics of Space. It examines various physical structures, the house in particular, as they have been depicted in literature. Like the best Continental theory, it draws on disciplines ranging from philosophy to psychology to physics as it describes seemingly familiar environments:

‘For our house is the corner of the world. As has often been said, it is our first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the word. If we look at it intimately, the humblest dwelling has beauty . . . . In short, in the most interminable of dialectics, the sheltered being gives perceptible limits to his shelter. He experiences the house in its reality and in its virtuality, by means of thought and dreams. It is no longer in its positive aspects that the house is really “lived,” nor is it only in the passing hour that we recognize its benefits. An entire past comes to dwell in a new house.’” [4]

Now, this something could be many things, and it is likely multivariable in nature: some conglomeration of economics, manufacturing, housing norms, location, demand, and style. But, to me, the principal aspect can be discovered through a discussion of ideals. Were it possible for each person to have the house of their choice, no parameters whatsoever, just what exactly would those houses look like? Under those conditions, I would wager that more homeowners would choose to have personally-tailored homes built: spaces that spoke to place, to family needs, and to individual tastes. I may be wrong about this, but this is where my intuition leads me. I think I can defend this proposition a bit more, however, and will do so through a few different works.

“In postwar France, the theorist Gaston Bachelard wrote a study called The Poetics of Space. It examines various physical structures, the house in particular, as they have been depicted in literature. Like the best Continental theory, it draws on disciplines ranging from philosophy to psychology to physics as it describes seemingly familiar environments:

‘For our house is the corner of the world. As has often been said, it is our first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the word. If we look at it intimately, the humblest dwelling has beauty . . . . In short, in the most interminable of dialectics, the sheltered being gives perceptible limits to his shelter. He experiences the house in its reality and in its virtuality, by means of thought and dreams. It is no longer in its positive aspects that the house is really “lived,” nor is it only in the passing hour that we recognize its benefits. An entire past comes to dwell in a new house.’” [4]

If the above quote contains truth, as I believe it does, then all humans have a desire for the familiarity of home: and that home signifies our known corner of the world, from which we sally forth to greet all manner of obstacles and travails. And because our pasts come to dwell with us, these homes contain, in a limited, personal sense, our cosmos. It is not obvious to me that such a house, according to these criteria, must be unique unto itself. It seems perfectly possible that a manufactured, or prefabricated, home could lend itself to constructing such a cosmos. But these are not the only things that should be considered.

In the architect and professor Christopher Alexander’s challenging book The Timeless Way of Building, he puts forward a theory for how buildings obtain life. And that, to him, is the chief element of any good building — extending even to a neighborhood or town. This life that a building has is, as he admits, impossible to describe precisely, though he does make the attempt:

“They are alive. They have that sleepy, awkward grace which comes from perfect ease. And the Alhambra, some tiny Gothic church, an old New England house, an Alpine hill village, an ancient Zen temple, a seat by a mountain stream, a courtyard filled with blue and yellow tiles among the earth. What is it they have in common? They are beautiful, ordered, harmonious — yes, all these things. But especially, and what strikes to the heart, they live. Each one of us wants to be able to bring a building or part of a town to life like this . . . Each one of us has, somewhere in his heart, the dream to make a living world, a universe.” [5]

In the architect and professor Christopher Alexander’s challenging book The Timeless Way of Building, he puts forward a theory for how buildings obtain life. And that, to him, is the chief element of any good building — extending even to a neighborhood or town. This life that a building has is, as he admits, impossible to describe precisely, though he does make the attempt:

“They are alive. They have that sleepy, awkward grace which comes from perfect ease. And the Alhambra, some tiny Gothic church, an old New England house, an Alpine hill village, an ancient Zen temple, a seat by a mountain stream, a courtyard filled with blue and yellow tiles among the earth. What is it they have in common? They are beautiful, ordered, harmonious — yes, all these things. But especially, and what strikes to the heart, they live. Each one of us wants to be able to bring a building or part of a town to life like this . . . Each one of us has, somewhere in his heart, the dream to make a living world, a universe.” [5]

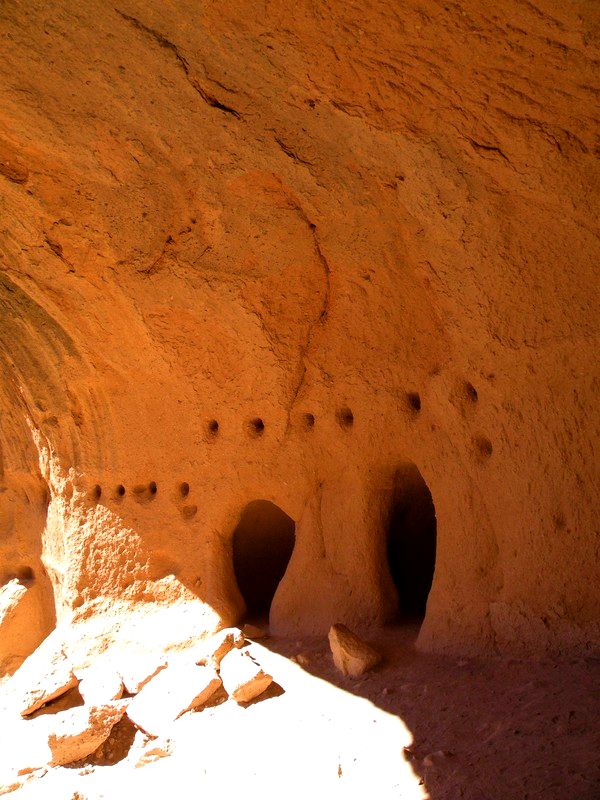

Two places that the author believes to embody Alexander's Timeless Way of Building: a pavilion at Lake Xianghu near Hangzhou, China and the Alcove House at Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico, USA. Photos taken by the author.

So, per this view, buildings are either alive or dead, life-generating or life-negating; moreover, this quality is something that we all simply and helplessly recognize, much as we all have moral intuitions and a sense of when things are logical or dangerous. Our inner forces pull us toward certain traits, and push us away from others. In buildings, as well as in towns, these traits are born of patterns that draw inspiration from the places they are in, as well as their connected cultures, people, and the habits of those people. And this is a key insight. If our buildings are constructed on an assembly line far from where they will eventually be built, with no thought of the people living inside of them, and with no thought as to how these houses will connect with the larger community, it seems as though we are creating lifeless, incoherent, and numbing structures. There is something to this, I believe, though the entire picture is a bit fuzzy, as is anything guided solely by “inner forces”. There are some areas of confusion stemming from such a view of architecture. For instance, what of modular homes that are constructed miles off site, but which are composed with both place and client in mind? Alexander would argue that these buildings are lifeless, as they do not spring organically from a design in the collective subconscious of a people; but surely this is a step above cookie-cutter houses placed in bleak rows? In a global world of intense economic competition and a robust international style of architecture, Alexander’s dream of timeless building seems far from a possible reality, beautiful though it is. Amidst this flux, the state of vernacular architecture is in a tenuous position, and many are considering the balance between our modern needs and our classic forms. [6] And there are further things to be considered.

It should be clear that specially-designed houses are not the obvious way forward. These homes certainly have a place in society, and in art, but the system that generates them cannot likely scale to a globalizing, developing world. So, how can we have an Architecture for All that simultaneously avoids the twin evils of economic discrimination on one hand and soulless art on the other? How do we contend with all the salient issues? The potential options seem to be instantiated, broadly, in prefabrication, modularity, and in the partially-manufactured house. As the manufactured house (built in factories and assembled on site) has become rather ubiquitous in the United States, as well as a symbol of “quality, speed and cheapness” it should seem logical that it is also widely accepted; yet, with public perception keenly aware that manufactured houses are simply modified trailers and mobile homes, class-based discrimination still exists concerning such houses. Their construction “is thought to be inferior, although it is in fact essentially the same as that of any other timber-framed house.” [7] And this brings us back to the heart of the problem: what constitutes a worthy house? Or, more broadly, what constitutes Architecture properly defined? Is it the industry that churns out hundreds of thousands of affordable houses each year to satisfied homeowners, or is the unique architectural solution that ultimately fails to make it anywhere except academic journals or art galleries? A simple analysis would seem to suggest that some measure of balance is possible: a home that is largely manufactured, yet assembled with respect to place and person. While the frames, construction materials, and rough forms are standardized and prefabricated, the ultimate composition could be constructed with an appreciative sense of land and imbued with embellishments that reflect both cultural traditions and individual sensibilities. Perhaps this is overly idealistic. Yet, there are similar and related movements in this vein already in existence, such as Critical Regionalism, which seeks to “engender a specific sense of self by attending to universal cultural elements as well as to the specifics of place” — a theory originally put forward by Kenneth Frampton in 1983. [8] Finding this mean between universality and specificity may prove difficult, as anyone who has navigated such disagreements knows, but it is not impossible. And the middle way often ends up being the best route forward.

In fine, there are many attendant issues that follow any discussion of prefabrication: questions of authorship and of architectural canon; problems of place and of identity; concerns over economic and environmental outcomes; worries about vernacular traditions; and, most interestingly, the idea that architecture as properly conceived may be more industry than inspiration — something that should discomfit any student of the arts. Holding all these tensions in mind, we can now turn to Hyrule, where such twentieth-century battles are yet unfought, and where people are simply concerned with recovering from a catastrophe which holds their lives in the balance.

It should be clear that specially-designed houses are not the obvious way forward. These homes certainly have a place in society, and in art, but the system that generates them cannot likely scale to a globalizing, developing world. So, how can we have an Architecture for All that simultaneously avoids the twin evils of economic discrimination on one hand and soulless art on the other? How do we contend with all the salient issues? The potential options seem to be instantiated, broadly, in prefabrication, modularity, and in the partially-manufactured house. As the manufactured house (built in factories and assembled on site) has become rather ubiquitous in the United States, as well as a symbol of “quality, speed and cheapness” it should seem logical that it is also widely accepted; yet, with public perception keenly aware that manufactured houses are simply modified trailers and mobile homes, class-based discrimination still exists concerning such houses. Their construction “is thought to be inferior, although it is in fact essentially the same as that of any other timber-framed house.” [7] And this brings us back to the heart of the problem: what constitutes a worthy house? Or, more broadly, what constitutes Architecture properly defined? Is it the industry that churns out hundreds of thousands of affordable houses each year to satisfied homeowners, or is the unique architectural solution that ultimately fails to make it anywhere except academic journals or art galleries? A simple analysis would seem to suggest that some measure of balance is possible: a home that is largely manufactured, yet assembled with respect to place and person. While the frames, construction materials, and rough forms are standardized and prefabricated, the ultimate composition could be constructed with an appreciative sense of land and imbued with embellishments that reflect both cultural traditions and individual sensibilities. Perhaps this is overly idealistic. Yet, there are similar and related movements in this vein already in existence, such as Critical Regionalism, which seeks to “engender a specific sense of self by attending to universal cultural elements as well as to the specifics of place” — a theory originally put forward by Kenneth Frampton in 1983. [8] Finding this mean between universality and specificity may prove difficult, as anyone who has navigated such disagreements knows, but it is not impossible. And the middle way often ends up being the best route forward.

In fine, there are many attendant issues that follow any discussion of prefabrication: questions of authorship and of architectural canon; problems of place and of identity; concerns over economic and environmental outcomes; worries about vernacular traditions; and, most interestingly, the idea that architecture as properly conceived may be more industry than inspiration — something that should discomfit any student of the arts. Holding all these tensions in mind, we can now turn to Hyrule, where such twentieth-century battles are yet unfought, and where people are simply concerned with recovering from a catastrophe which holds their lives in the balance.

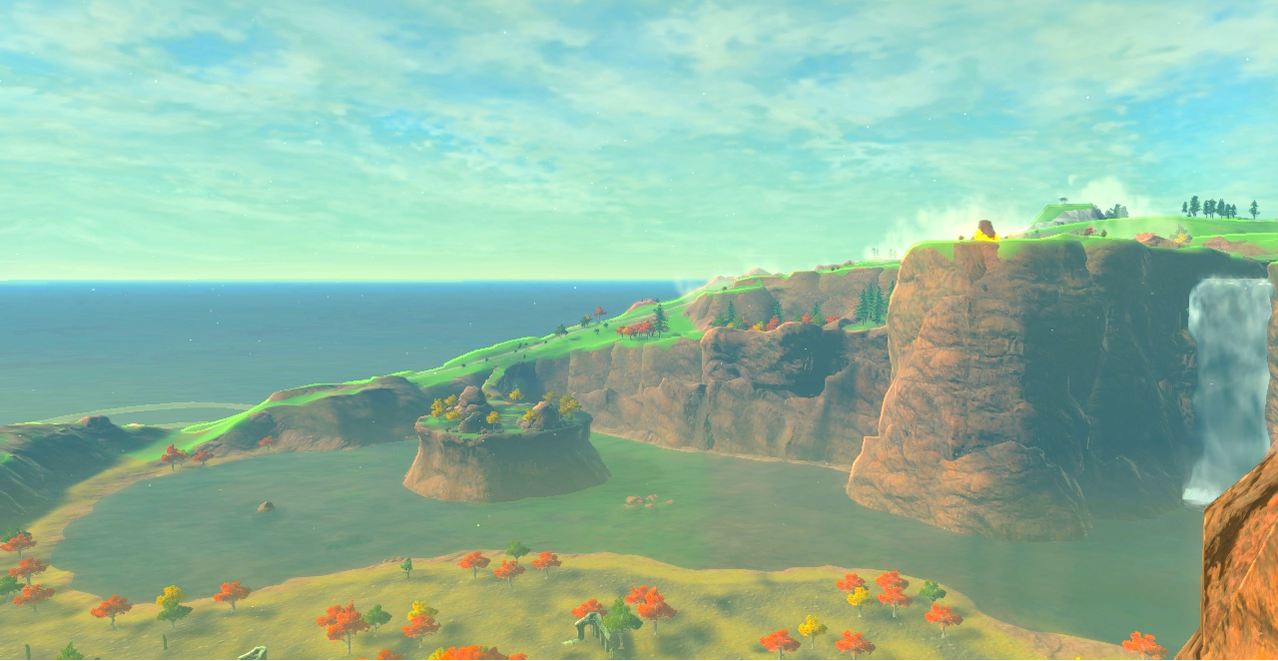

An uninhibited view of the beautiful environment in which Tarrey Town will eventually come to be built.

Hyrule’s experiment with modular, prefabricated architecture is an absolute romp, in honesty, and this venture is reified through the delightful side-quest From the Ground Up. While the quest itself begins in Hateno Village, it eventually unites a new clan of people based solely around nomenclature in the far hinterlands of Akkala; Link must travel Hyrule, visiting each people and every settlement, searching for individuals all bearing the patronym -son. [9] That this should be the unifying force in the creation of a town is charming and more than a little kitschy, but it easily proves the most endearing side-quest in Breath of the Wild.

While Tarrey Town is the brainchild of the industrious Hudson, it is Link who puts in much of the legwork, gathering resources and recruiting new townspeople to populate the settlement. As Link progresses, delivering more and more lumber to Hudson, the village grows apace, swiftly forming a pluralistic and diverse community. Resting under the historied shadow of the ancient Akkala Citadel Ruins, Tarrey Town has an almost perfect position upon a natural outcropping of rock in Lake Akkala connected to the mainland only by a stone bridge. It is a rather odd geological formation, but it is quite well-suited to a small community. The land is circular, flat, and arable, and its town eventually becomes one of the most enchanting places in all of Hyrule — likely among the newest settlements, if not the newest, since the Calamity a century ago.

While Tarrey Town is the brainchild of the industrious Hudson, it is Link who puts in much of the legwork, gathering resources and recruiting new townspeople to populate the settlement. As Link progresses, delivering more and more lumber to Hudson, the village grows apace, swiftly forming a pluralistic and diverse community. Resting under the historied shadow of the ancient Akkala Citadel Ruins, Tarrey Town has an almost perfect position upon a natural outcropping of rock in Lake Akkala connected to the mainland only by a stone bridge. It is a rather odd geological formation, but it is quite well-suited to a small community. The land is circular, flat, and arable, and its town eventually becomes one of the most enchanting places in all of Hyrule — likely among the newest settlements, if not the newest, since the Calamity a century ago.

Although defensible, it is still welcoming, as indeed the sign above the gate reads. The gate is almost a direct copy of the gates leading into Hateno Village — certainly an homage to their creator’s hometown far away. The path leading through the village is one both simple and agrestic: a series of wooden boards set into the earth which provides just the right amount of subtle direction: a trail somewhere between civilization and wilderness. The absolute center to this town is the community’s shrine to Hylia, which is set into a hexagonal setting reminiscent of a rupee (likely tipping its hat to the town’s commercial roots); the construction of this setting is really quite stunning: the wood is of significant quality, highly polished and tightly-fitted. Upon a small dais in the middle of the fountain is the statue to Hylia, which rests over a placard bearing the word “builders”. The statue is framed by two lanterns, and behind her, as well as on the four rear sides of the pool, are tall stele-like columns with rectangular holes and stylized hearts. These columns are the source of water for this fountain, and several diminutive waterfalls flow out of each down into the pool below. On nearly every piece of wood is engraved the word “builders”, making this almost a protective shrine for construction workers as well as an advertisement of sorts. Behind Hylia’s form are drawn an additional set of wings in white, hovering slightly above the stone wings, but to unknown purpose. The overall image is very homey, as if the villagers have made every aspect of their lived space into something overflowing with personality and charm.

From the six sides of this pool run the six paths toward the town’s six buildings. Everything is in a rough, organic symmetry within the village’s hexagonal plan, with five houses and one hotel. Noticeably, there are no solid, lasting stores; each race present in Tarrey Town has taken up shop outside the houses, selling various items from their respective provinces and backgrounds. The feeling is incredibly homelike, as the central plaza is the life of the community — the place where everyone gathers, exchanging stories, food, and memories. Like a cul-de-sac, the layout of this town focuses all movement toward its center, providing an optimal location for meeting and congregation: a true neighborhood.

From the six sides of this pool run the six paths toward the town’s six buildings. Everything is in a rough, organic symmetry within the village’s hexagonal plan, with five houses and one hotel. Noticeably, there are no solid, lasting stores; each race present in Tarrey Town has taken up shop outside the houses, selling various items from their respective provinces and backgrounds. The feeling is incredibly homelike, as the central plaza is the life of the community — the place where everyone gathers, exchanging stories, food, and memories. Like a cul-de-sac, the layout of this town focuses all movement toward its center, providing an optimal location for meeting and congregation: a true neighborhood.

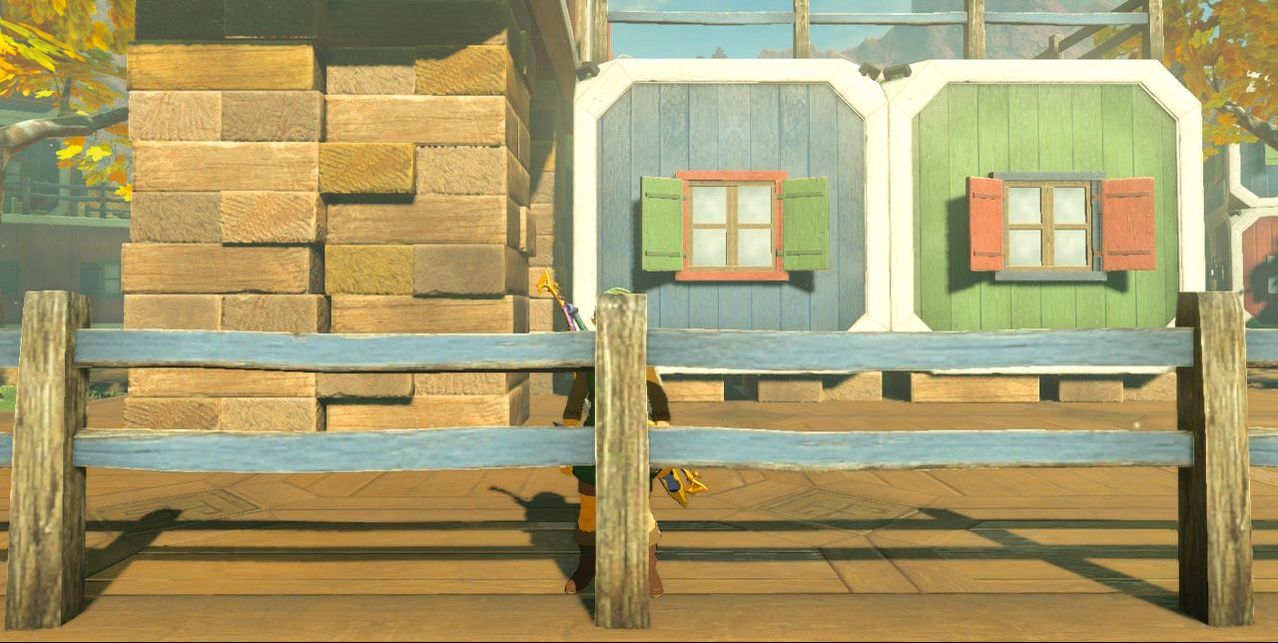

For all its simplicity, the architecture present in Tarrey Town might be the most memorable in Breath of the Wild. Modular in design, the forms allow the occupants to assemble the prefabricated pieces as they need them; with this comes a huge amount of freedom, even within a highly-constrained system, for even a formalized style cannot hide all variation. The modules are in one- and two-piece cubes, which makes for easy assembling and future additions. [10] The colors too are simplistic, in muted hues of red, green, and blue, reflecting the sacred colors of the goddesses. (This was a fascinating connection, to me, although we do not know if the designers made these the colors with any religious meaning in mind.) All of the modules are framed in white trim, and the windows and shutters are plain, only differentiated by the three colors in different combinations. There are two primary types of building configurations in Tarrey Town, though there are three total types of these buildings, and, like the shutters and windows, they differ only slightly in their subtler elements. Each house is set upon thick boards, elevating it from the ground, and second-story elements are usually held up by massive stacks of thick-cut lumber.

All the houses in this community have smaller second stories with upstairs balconies, usually set overlooking the common plaza, again asserting the communal essence of this place. These balconies range from spare to ample, with some having only chairs, while others have picnic tables, benches, stools, and potted plants. Above the second stories are the rooflines of the structures. They resemble the room-based modules of the first and second stories, only cut off at the quarter mark and covered in a wood-shingled roof. Small triangles rest upon the roofline, providing contrast against the sky, like the capstone on a pyramid. And these designs are not simply to be found upon the rooflines of Tarrey Town, but also in its flowerpots. While at a significantly smaller scale, the planters mimic inverted roofs, open from the top and full of soil and growing things. Others are simply capped with the pyramidal shapes described above. These seem purely decorative — one of the only embellishments at play in this settlement.

All the houses in this community have smaller second stories with upstairs balconies, usually set overlooking the common plaza, again asserting the communal essence of this place. These balconies range from spare to ample, with some having only chairs, while others have picnic tables, benches, stools, and potted plants. Above the second stories are the rooflines of the structures. They resemble the room-based modules of the first and second stories, only cut off at the quarter mark and covered in a wood-shingled roof. Small triangles rest upon the roofline, providing contrast against the sky, like the capstone on a pyramid. And these designs are not simply to be found upon the rooflines of Tarrey Town, but also in its flowerpots. While at a significantly smaller scale, the planters mimic inverted roofs, open from the top and full of soil and growing things. Others are simply capped with the pyramidal shapes described above. These seem purely decorative — one of the only embellishments at play in this settlement.

|

The stacked lumber supports of Tarrey Town, which brace various balconies and second-story additions. Also notice the color pattern of alternated green, red, and blue.

|

Some decorative planters in Tarrey Town. The central planters are miniaturized house modules, while the outer planters mimic the roof modules seen in back.

|

While on the topic of nature, we would be remiss to not mention the stunning setting that surrounds this place. Most of the town is blanketed in a verdant grass, and newly-planted trees spring to life between the houses. These stand in the foreground to massive, sky-wide-open views of mountains and fields, a breathtaking landscape with almost inimitable views. Tarrey Town is truly fortunate for its location.

After dark, the populace heads indoors, retreating into the family and the warm glow of home. The interiors, while the most varied design aspect in this community, still have many elements in common. It is likely that all the furniture and effects in these homes were also mass-produced (or at least made by the same artisan), as they all take the same form and bear the same maker’s mark (the stylized heart seal discussed before). These odds and ends range from flower pots to doors, and from bookshelves to dressers. The homes are notable for their very sparse and minimalistic furnishings: lanterns, desks, stools, beds (on simple planks), books, wardrobes, stoves, and kettles make up the entirety of cultural artifacts in Tarrey Town.

A few indoor shots of the houses of Tarrey Town.

I am led to wonder about the creation of this town. Was it born of Hudson’s desire for isolation? For peace? Out of curiosity and a drive to create? Is it an environmental movement that uses local resources and sustainable building techniques, or is it primarily an intentional community of varied races all united around a common cause? It is certainly true that the town seems perfectly pluralistic, with members of all races present, each bringing an element of their home culture to the town. Perhaps that is the point: that such a society can exist in peace, so long as they are tied up in common goals, aspirations, and beliefs. And if that is indeed the goal of Tarrey Town, then the prefabricated, modular architecture makes a great deal of sense. Not only does it allow for swift construction, but it is more readily available to people of scarce means; even more critically, in its simplest form it obliterates all outer trappings of class, for everyone shares the same style of home in roughly the same form, of the same materials. These are not the favelas of Brazil, starkly contrasting crippling poverty with unnecessary luxury, but utilitarian buildings of simple means meant to unite through commonality, not discriminate through difference. And this is a key component of any stable society. Once every family has their basic needs met, then the society as a whole can move toward humanity’s higher goals: understandings of self, of place, and of shared meaning.

Perhaps the most important lesson that I learned from Tarrey Town is this: prefabricated homes can also share in beauty. There is nothing innate in modular architecture that ensures ugliness; just as with architect-designed homes, modular houses flow over the entire spectrum of design and aesthetics. As Davies writes, “Prefabricated buildings can be temporary or permanent, cheap or expensive, all the same or all different, small or large, traditional or modern, well designed or badly designed. They are not intrinsically mean or base and they do not necessarily make soulless places. A garden shed can be more enchanting than a luxury villa; a roadside restaurant can be as pleasant as a pavilion in a park. It is a question of judgement, of caring about the building and its future life, of knowing how to strike the right balance between standard products and special places.” [11] And that is the wisdom to be gleaned here: architecture is the most widespread form of art that is constantly accessible to everyone. To that end, we can more clearly make choices concerning its future. Do we want to create egoistic, hideous constructions that please only the most hardline architectural theorists, or do we want beautiful and engaging architectural designs that are affordable for everyone while losing none of what architecture can give? It seems that we have not yet struck the right chord. We have yet to figure out just what that future looks like. But, if it looks at all like what Tarrey Town symbolizes, then it will be a happy future indeed.

Perhaps the most important lesson that I learned from Tarrey Town is this: prefabricated homes can also share in beauty. There is nothing innate in modular architecture that ensures ugliness; just as with architect-designed homes, modular houses flow over the entire spectrum of design and aesthetics. As Davies writes, “Prefabricated buildings can be temporary or permanent, cheap or expensive, all the same or all different, small or large, traditional or modern, well designed or badly designed. They are not intrinsically mean or base and they do not necessarily make soulless places. A garden shed can be more enchanting than a luxury villa; a roadside restaurant can be as pleasant as a pavilion in a park. It is a question of judgement, of caring about the building and its future life, of knowing how to strike the right balance between standard products and special places.” [11] And that is the wisdom to be gleaned here: architecture is the most widespread form of art that is constantly accessible to everyone. To that end, we can more clearly make choices concerning its future. Do we want to create egoistic, hideous constructions that please only the most hardline architectural theorists, or do we want beautiful and engaging architectural designs that are affordable for everyone while losing none of what architecture can give? It seems that we have not yet struck the right chord. We have yet to figure out just what that future looks like. But, if it looks at all like what Tarrey Town symbolizes, then it will be a happy future indeed.

Notes and Works Cited:

[1] Davies, Colin. “Introduction.” The Prefabricated Home, Reaktion, 2005, p. 9.

[2] Ibid., p. 43.

[3] Ibid., p. 67.

[4] Petty, Adam Fleming. “The Spatial Poetics of Nintendo: Architecture, Dennis Cooper, and Video Games.” Electric Literature, 1 Dec. 2015, www.electricliterature.com/the-spatial-poetics-of-nintendo-architecture-dennis-cooper-and-video-games-346fc1eec95f.

[5] Alexander, Christopher. The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford University Press, 1979, pp. 8-9.

[6] Keskeys, Paul. “Is Vernacular Architecture Dead?” Architectural Digest, Condé Nast, 31 July 2018, www.architecturaldigest.com/story/vernacular-architecture-china-tel-aviv-new-york-london.

[7] Davies, Colin. The Prefabricated Home, Reaktion, 2005, p. 82.

[8] Banai, Nuit, and Alisa Beck. “Critical Regionalism: Between Local and Global.” Guggenheim, 13 Apr. 2017, www.guggenheim.org/blogs/map/critical-regionalism-self-maintenance-between-local-and-g

[9] Hudson was sent to the Akkala region by Bolson to create an extension of the Bolson Construction Company. One of the policies of this company requires that each employee must bear a last name ending with -son. Thankfully, this is a patronym that crosses all cultures. These new citizens include Greyson and Pelison of the Gorons; Rhondson, a Gerudo woman of the desert; Fyson, a Rito; and Kapson, a priest from Zora’s Domain. Of course, these are not the only people living in Tarrey Town; others with less demanding names also make their home in the community.

[10] "Bolson's stacking method is a way of building that was dreamed up by Bolson himself. It has no precedent in the history of Hyrule. It is extremely simple — these square rooms are simply stacked together and locked into place. Then you can add a wooden deck or flower bed in whatever way you choose. They ship the town lights directly from Hateno Village, which is the home of Bolson Construction. With a single adult Goron, anyone can easily create a stacked building. They can be freely and easily arranged as well. Of course, they are easy to break down and can be transported later as you see fit."

White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 291. Dark Horse Books, a Division of Dark Horse Comics, Inc., 2018.

[11] Davies, Colin. The Prefabricated Home, Reaktion, 2005, pp. 203-4.

[1] Davies, Colin. “Introduction.” The Prefabricated Home, Reaktion, 2005, p. 9.

[2] Ibid., p. 43.

[3] Ibid., p. 67.

[4] Petty, Adam Fleming. “The Spatial Poetics of Nintendo: Architecture, Dennis Cooper, and Video Games.” Electric Literature, 1 Dec. 2015, www.electricliterature.com/the-spatial-poetics-of-nintendo-architecture-dennis-cooper-and-video-games-346fc1eec95f.

[5] Alexander, Christopher. The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford University Press, 1979, pp. 8-9.

[6] Keskeys, Paul. “Is Vernacular Architecture Dead?” Architectural Digest, Condé Nast, 31 July 2018, www.architecturaldigest.com/story/vernacular-architecture-china-tel-aviv-new-york-london.

[7] Davies, Colin. The Prefabricated Home, Reaktion, 2005, p. 82.

[8] Banai, Nuit, and Alisa Beck. “Critical Regionalism: Between Local and Global.” Guggenheim, 13 Apr. 2017, www.guggenheim.org/blogs/map/critical-regionalism-self-maintenance-between-local-and-g

[9] Hudson was sent to the Akkala region by Bolson to create an extension of the Bolson Construction Company. One of the policies of this company requires that each employee must bear a last name ending with -son. Thankfully, this is a patronym that crosses all cultures. These new citizens include Greyson and Pelison of the Gorons; Rhondson, a Gerudo woman of the desert; Fyson, a Rito; and Kapson, a priest from Zora’s Domain. Of course, these are not the only people living in Tarrey Town; others with less demanding names also make their home in the community.

[10] "Bolson's stacking method is a way of building that was dreamed up by Bolson himself. It has no precedent in the history of Hyrule. It is extremely simple — these square rooms are simply stacked together and locked into place. Then you can add a wooden deck or flower bed in whatever way you choose. They ship the town lights directly from Hateno Village, which is the home of Bolson Construction. With a single adult Goron, anyone can easily create a stacked building. They can be freely and easily arranged as well. Of course, they are easy to break down and can be transported later as you see fit."

White, Keaton C., and Shinichiro Tanaka. The Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild: Creating a Champion, p. 291. Dark Horse Books, a Division of Dark Horse Comics, Inc., 2018.

[11] Davies, Colin. The Prefabricated Home, Reaktion, 2005, pp. 203-4.